Women More Educated Than Men But Still Paid Less

Women More Educated Than Men But Still Paid Less

NEW YORK: In recent years women have risen to the top of the corporate world. From Indra Nooyi at Pepsico to Mary Barra at General Motors, the rise of women to CEO of major companies has been celebrated. More noteworthy has been the dominance of women in higher education. After centuries of male dominance, worldwide women now outnumber men in both university attendance and graduation. Yet these impressive gains have been limited by and large to developed nations, and even there disparity and discrimination call for continuous struggle. Broader society must acknowledge and address the pressures of this gender schooling divide.

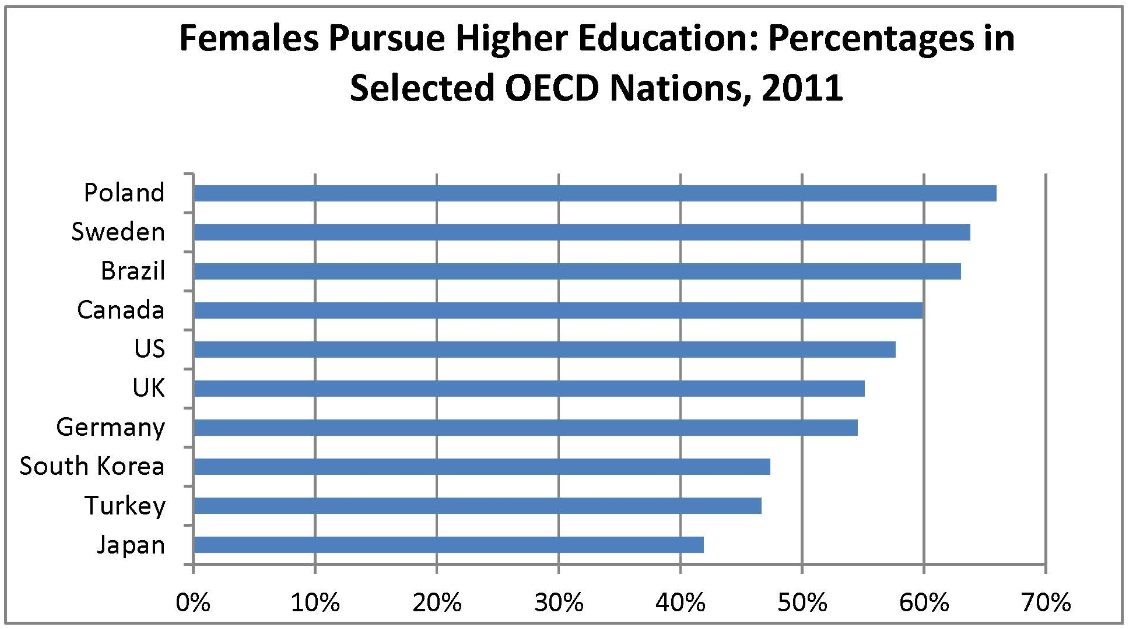

University enrollment parity between the sexes was achieved shortly after the start of the 21st century. Since then average ratios of university participation of women have surpassed men. While the average global university enrollment ratio in 1970 was 160 men per 100 women, today it stands at around 93 men per 100 women. Women’s university enrollment ratios exceed those of men in two out of every three countries with data. In nearly all countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the majority of university graduates are women (see graph). In some countries, such as Estonia, Iceland and Poland, about two-thirds of university graduates are women. Notable exceptions are Japan, South Korea and Turkey, where the proportions of female university graduates are between 40 and 50 percent.

In the largest OECD country, the United States, women are almost 60 percent of the annual university graduates and more than 70 percent of 2012 high school valedictorians. Women account for 60 percent of master's degrees and 52 percent of doctorates being awarded in the US.

Although men continue to outnumber women in university enrollment in some developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, in many others, such as Argentina, Iran, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, women constitute the majority of university students. Among the world’s two largest populations, China and India, women are moving toward parity with men in university participation, 48 and 42 percent, respectively. Despite these educational gains, women continue to lag behind men in employment, income, business ownership, research and politics. This pattern of inequality suggests that societal expectations and cultural norms regarding appropriate roles for men and women and inherent biological differences between the sexes limit the benefits of women’s advantage.

Differences between men and women are apparent at the earliest ages. Researchers observe that boy and girl babies differ even in the crib, with boys more visually alert and physically active and girls more vocal and sensitive to sounds. Girl toddlers tend to mature more quickly than boy toddlers and develop language skills sooner. Sex differences in educational achievement are evident in early childhood. Even before primary school, boys tend to be behind girls in educational development, especially verbal skills. Teachers report that girls are more prepared to enter school than boys and find that girls begin reading at earlier ages than boys. Numerous country studies at the secondary-school level have found that, on average, girls consistently score higher in reading skills, while boys exceed slightly in mathematics.

In general, girls outperform boys with better classroom grades, teacher assessments and scores on college entrance exams. As a result, some universities have adopted affirmative action policies for boys to achieve a desired sex balance in student enrollment. Among OECD countries women’s college completion rate is on average 10 percentage points higher than men’s.

Closer examination of university education, however, indicates significant differences in fields of study chosen by men and women. Whereas men dominate in such fields as engineering, manufacturing, computer sciences, often exceeding 80 percent of bachelor’s degrees, women are concentrated in fields that are less remunerative such as education, humanities and arts, and health and welfare. Even in countries that strive for gender quality, such as Sweden, women account for about 60 percent of the college students majoring in the humanities versus 30 percent in engineering, manufacturing and construction.

Despite their educational advantage, college women have lower rates of employment than male counterparts in most countries, though the gap has decreased recently. Across OECD countries, for example, the employment rates among the college-educated aged 25 to 64 years are lower for women than college men, about 80 percent versus 90 percent on average with larger differences in some countries, including Japan, South Korea and Turkey. Also, in many Arab countries, such as Lebanon, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, women make up the majority of university students but constitute a minority of the labor force. Those women who decide to join the labor force and advance their careers often interrupt their employment with motherhood responsibilities. Career interruptions of several years or part-time employment for child-rearing hinder the rise of college-educated women to high echelons in industry, research and government. These women are also more likely than men to take time off from employment for family matters, including care for elderly relatives.

With women outnumbering men on most college campuses, there are relative shortages of educated men. Highly educated and socially autonomous women in particular are encountering difficulties in meeting and dating marriageable, equally successful men. In Australia, for example, one in four of degree-educated women in their 30s are expected to miss out on finding a suitable male partner of similar age and educational attainment. Women increasingly face the choice of marrying below their educational level – something both men and women have traditionally avoided – or not marrying at all.

Women’s educational advantage also has demographic effects on marriage, divorce and birth rates.Well educated and financially self-sufficient women are less likely to feel a need to marry; if married, they are less willing to tolerate a troubled relationship. In addition, those pursuing professional careers or already in high-level positions are more likely to remain childless or have a single child.

Perhaps additional time is needed for women’s educational advantage to bring about gender equality across major social, economic and political realms of society. In the meantime, societies could enact measures to benefit from the skills and talents of women and overcome the limitations of the glass ceiling. Greater efforts, for example, are needed to overcome gender stereotypes that reinforce status, hierarchies, biases and sexism. Adoption of gender-sensitive legislation would promote equality between the sexes, including equal pay for equal work and access to finance for women. More flexible work schedules, improved parental leave policies and greater opportunities for women to rejoin the workplace after short interruptions due to family building would also facilitate gender equality.

While widely accepted that boys and girls should have the opportunity to pursue a career of their own choosing, many educators would like to require, or at least encourage, that both sexes take the same coursework throughout the secondary level, including math, science, humanities and the arts to achieve similar gender balances in professions. Finally, while few would dispute the individual and societal benefits of women’s educational achievements, parents, teachers and policymakers are increasingly troubled by men’s educational performance falling behind women, especially in developed economies. At the primary level boys are generally less interested, motivated and engaged in schoolwork than girls. Dropout rates at the secondary level tend to be higher for boys and those who complete secondary are less likely to attend college. Achieving educational equality among the sexes requires special attention aimed at improving the education of boys and men.

Joseph Chamie is a former director of the United Nations Population Division.

A French translation of this article was provided by Mathilde Guibert.

A Ukrainian translation of this article was provided by Anna Matesh.

A Romanian translation of this article was provided by Ecaterina Ștefănescu.

Comments

The article was translated to Ukrainian by Anna Matesh.

http://eustudiesweb.com/women-more-educated-than-men-but-still-paid-less/

So, should we pay women with degrees in useless area, the same we pay for jobs that are worth more? Sounds like the article is more about wining and less about any real problem.

*whining