World Ignores Mass Detentions of Migrants

World Ignores Mass Detentions of Migrants

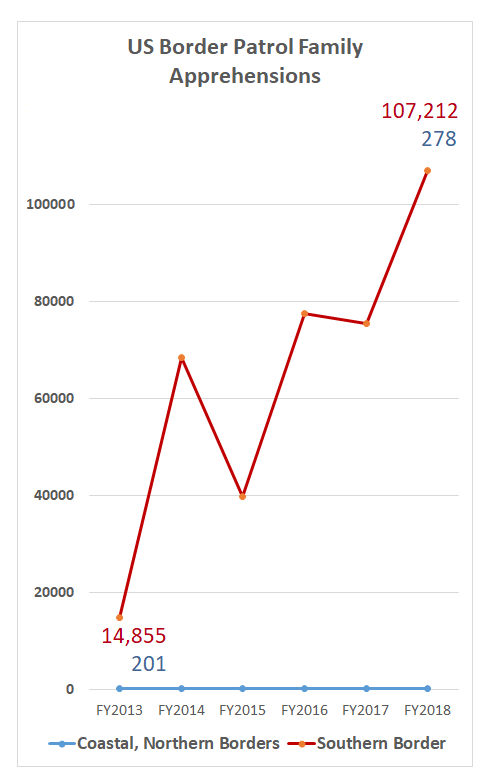

NEW HAVEN: The public outcry was immediate, massive and powerful after the Trump administration announced its “zero tolerance” strategy in 2018, leading to the mass forced separation of migrant parents and children and mandatory incarceration of asylum seekers. Thousands of citizens, human-rights organizations and religious leaders united in condemning this policy. In contrast to this condemnation, governments around the globe stayed silent. That ominous silence speaks volumes about sharply eroding human rights all over the world.

Nevertheless, the public outcry led to denials, blame and temporary slippage in the government migration-control strategy based on deterrence. The administration reserved the option to return to the policy if numbers of border arrivals continued to soar. Sources suggest that the government did not really abolish the separation policy, with methods only becoming more subtle and mischievous.

As images and audio footage of crying children in cages and holding facilities went viral, attorneys and NGOs applied public pressure and invoked legal domestic and international measures. On the domestic level, several cases were filed on behalf of separated families. In June 2018, a federal judge in California ruled in favor of reunification of children under the age of five with parents within 14 days. At the international level, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, IACHR, granted pecuniary measures in August in favor of migrant children forcibly separated from their families on the basis of this policy. IACHR is an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States that examines allegations of human rights violations of the American Convention on Human Rights, though the United States is one of the few member states that has not ratified the convention and thus does not consider itself bound by the commission’s decisions. Several Latin American national human rights organizations and law firms filed submissions on behalf of detained children to IACHR, with the commission requesting that the United States adopt necessary measures to protect the rights to family life, personal integrity and identity of families, assuring reunification and communication guarantees. Even the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights condemned family separation as a violation of international law and demanded immediate halt.

The US response was prompt and harsh. The administration, similar to leaders in China or Russia, rejected external criticism as interference in US internal affairs demonstrating disregard for international legal standards and protections for refugees. As the New York Times reported, the US ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley responded to the UN High Commissioner’s criticism, by stating, “once again, the United Nations shows its hypocrisy by calling out the United States while it ignores the reprehensible human rights records of several members of its own Human Rights Council.”

While neither constructive nor reasonable, Haley’s retort contains a kernel of truth: Multiple members of the UN Human Rights Council rode roughshod over the human rights of migrants and asylum seekers – and this may be why, despite the outcry worldwide, other governments have backed off. For example, the media often portrays the US neighbor to the north, Canada, as an exemplary role model when it comes to protecting migrants and asylum seekers. Yet reports suggest that Canada has also separated children from parents or guardians since 2015. Ironically, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was one of the few foreign leaders who spoke out against the US zero-tolerance policy. While the scale of Canada’s separations was smaller, the fact remains that criminally charging asylum seekers for entering a state’s territory and relying on such charges to separate families is a violation of binding international treaty law and custom. Criminalizing migration in general and the mass incarceration of asylum seekers violate universally applicable and binding standards such as the Refugee Convention, the prohibition of torture, the duty to consider the best interest of the child, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and other conventions and principles. Furthermore, international law dictates that children must not be incarcerated on the basis of parents’ migration status.

Separating asylum-seeking families is rare, and migrants and asylum seekers face horrific conditions in high-income countries that could afford more humane treatment. The wealthy countries try to send a message to those seeking protection from war, natural disaster, financial distress and persecution: Do not come, you are not welcome, and if you come, expect a long and painful asylum process.

The United States is not alone. In 2017, courts in Australia ordered the government to pay $70 million plus costs to refugees and asylum seekers who had suffered physical and mental injuries in offshore Manus Island detention centers. Conditions in such centers were so dire, constituting such a massive violation of international human rights standards, that they arguably reached the threshold of a crime against humanity as reflected in a case communicated to the International Criminal Court. In Israel, those entering irregularly face indefinite detention without trial. Asylum seekers who enter through Egypt are immediately returned without the possibility of presenting any claims for protection, a violation of the binding customary prohibition of collective expulsion.

Some European Union member states have gained a notorious reputation, too. Several refugee camps in Greece violate numerous standards set by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and UN reports reveal inhumane standards: mandatory detention, overcrowding in inadequate tents even with freezing temperatures, up to 190 refugees sharing one toilet, minimal medical assistance and the spread of infectious diseases, along with omnipresent violence. In Hungary, xenophobic rhetoric of President Viktor Orbán only adds to the degradation and mistreatment. The European Court of Human Rights ordered Hungary in 2018 to provide food to asylum seekers in a camp on the border with Serbia, whose cases were still pending, The country had hoped to coerce the asylum seekers to return to Serbia. Reports of a Hungarian policy to detain children in cages received little attention beyond the circles of human-rights activists. Unfortunately, xenophobic sentiments outside Hungary and all over Europe have been on the rise, fueling the Brexit decision and election of right-wing politicians in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and elsewhere.

Countries have the legal obligation to provide humane treatment for asylum seekers during the asylum process. International binding standards that these states agreed to follow prohibit criminalization of asylum seekers for entering a state’s territory, incarceration, and separation of children from their parents and caregivers, and require allocation of primary care. Yet states around the globe intentionally fail to do so, instead engaging in a race to the bottom in restricting such guarantees. The intention behind this deliberate degradation of standards is to deter asylum seekers from seeking protection. As states undercut each other in their migration-control strategies based on deterrence, they not only erode the established international asylum standard, but also destroy their own credibility in pointing out heinous violations in other states without seeming hypocritical.

Hence, few western governments publicly condemned the US family-separation policy. Civil society, human rights activists, institutions and some judges on a domestic, regional and international level remain the leaders in this battle against politically motivated and selfish cruelty.

Lena Riemer is a Fox International Fellow at Yale’s MacMillan Center and a jurist. She is pursuing her PhD at Freie University Berlin in the field of international migration and asylum law. Her research interests lie mainly in the area of international criminal law, migration and asylum and human rights, and she provides legal counseling for asylum seekers.