Wrong-Way Bets on Oil

Wrong-Way Bets on Oil

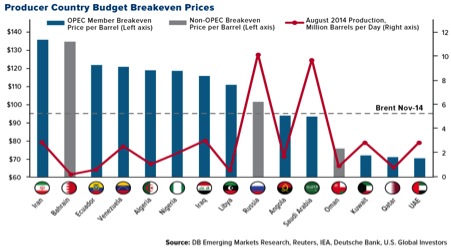

DAEJEON: Oil prices worldwide are collapsing on an unprecedented scale, most recently below $50 per barrel. This is having serious effects on the one-horse oil and gas OPEC member economies of Nigeria, Ecuador, Libya, Algeria, Venezuela, some of which have predicated entire national budgets on a scenario of $110 a barrel or higher oil, or in Iran’s case, $135 a barrel. Russia’s economy especially has been victimized by falling oil prices with the ruble practically halved in value by late 2014. What the markets call a “wrong-way” bet will have significant national and global economic consequences.

The low prices lure developing nations into dependence on fossil fuels rather than developing infrastructure and preparing for alternatives. In particular, the countries that have refused to diversify their economies into other industries, such as manufacturing, textiles, agriculture or tourism, now reap a large economic comeuppance.

Markets are predicting oil to slide to $40 a barrel, and some bearish forecasters even predict $20 a barrel by the end of 2015 – if the US dollar appreciates against all other currencies with low oil prices, especially Asian currencies, and currency wars re-ignite. For now, the US economy is becoming the main driver of world growth; however the US cannot perpetually be the importer of last resort for the rest of the world.

Asia is stagnating, and the eurozone is faltering, facing possible deflation, in part due to an ongoing conflict with Russia and Ukraine. If prices, in fact, do fall below $40 barrel, then fuel is far below being subsidized and, in essence, Indonesians, Indians and Malaysians would be paying actual market, not subsidized prices.

The consumer fuel subsidy thus ceases to exist.

The 2009 financial crisis laid many countries economies bare. With central banks engaging inso-called quantitative easing and vast liquidity of dollars seeking higher yields sloshing around, Asian and Middle East and North Africa economies in particular, from Egypt to Indonesia seek to amplify theirexport models once again. Conversely, Indonesia has also predicated much of its fuel subsidy budget on oil at $105 barrel for 2015 and Malaysia, both significant user and exporter of oil, at $85. At current oil prices, Indonesia is already nearly 50 percent below this metric projection.

On November 18, new Indonesian President Jokowi Widowo essentially cut consumer fuel subsidies to zero by raising the price of subsidized fuel to US$0.71 per liter. On November 22, Malaysia followed suit, completely scrapping consumer fuel subsidies altogether. Effectively then, with oil below subsidized prices, refiners cutting margins and a glut of supply, a parity level with market prices for all extensive purposes exists. At one point, Malaysia’s subsidized fuel price of petrol was trading slightly above market prices at US$0.62 per liter. As of this writing, Indonesia has readjusted prices downward to US$0.61, in line with Malaysia and lower than Jokowi’s initial cut.

Any “windfall dividend” must be handled correctly. To do this, nations must have better infrastructure and the power generation that goes with it. For countries that subsidize fuel, most if not all economic scenarios are predicated on utilization of fossil fuels, from longer freeways with petrol burning cars, deeper ports with bitumen-powered shipping, electricity generation with more coal, and bigger airports servicing kerosene-fueled discount airlines. For example, Indonesia’s Jokowi has proposed an ambitious infrastructure rebuilding to get the Indonesian economy moving, particularly for employment. Specifically, “… between 2015 and 2019, the government plans … 2,600 kilometers of new roads; 1,000 kilometers of new toll roads; 15 airports; 24 sea ports; and expand the railway network by 3,258 kilometers” – all based on fossil fuels.

In India, falling oil prices will bring relief to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government and his economic reforms. In Malaysia, a costly problem has been alleviated, but a new one emerges, as so much of the economy depends on oil exports at $85 barrel. In the case of Indonesia and India, both democracies, the leaders have erased subsidies early in their terms to avoid voter wrath down the road. All three leaders promise improved social spending and programs with the fuel subsidy reduction.

But therein lies part of the problem, as governments do not address producer fuel subsidies, that is institutions such as oil, infrastructure and utility companies creating the dependence on continuing use of fossil fuels, thus representing a far costlier long-term commitment. All three countries predicate their economic rebound entirely on continued usage of fossil fuels, with no discernible carbon dioxide reduction targets promulgated by either Jokowi or Modi, and of course a belief that exports will pick up due to more business-friendly investment rules and cheaper labor.

Ironically, the World Bank and the UN International Panel on Climate Change, just as oil prices began falling, issued global warming reports over average increase in global temperatures, with 2014 on course to be the hottest year on record. Many developing countries rushing towards a economic recovery based on low-priced oil are the same countries that will suffer the most from floods, superstorms, heatwaves and prolonged drought. A perfect storm is brewing.

The real problem lies in aggregation. If it were only, say, Indonesia burning more fossil fuels for economic growth, the strategy could perhaps be justified, but every country in the Association of South East Asian Nations, indeed all greater Asia, including China, India, Japan and Korea are predicating greater economic growth on utilization of more fossil fuels: China with monstrous airport capacity in Pudong, Beijing and Chengdu; India with more coal-burning electric plants coming online, some still World Bank funded; Japan using combined-cycle gas plants to make up for lost electric generation after the Fukushima disaster; South Korea building deeper ports in Busan, Incheon and Jeju to enhance their export shipments. Besides climate change scenarios, when and not if oil prices begin to climb, inflation will become a force to be dealt with due to rising energy costs.

The consequences could be severe. Consumers’ fuel subsidies still provide an imperfect advantage for competitiveness in developing countries by essentially keeping labor costs low. Fuel subsidy savings should be used for budgeting; incentives for wind, photovoltaic and geothermal power generation should be at the vanguard of any 21st century environmentally friendly infrastructure plan, in any country. Longer term planning should include an array of hydropower dams, undersea power with tides and nuclear power. But the nuclear option requires a workforce highly capable of harnessing its vast power and understanding of the huge safety demands with a disciplined mindset for details.

Perhaps the best advice would be to not eliminate subsidies entirely – yet – amidst falling oil prices. Watchful waiting may be a better scenario. Even if the funds from a subsidy cut are allocated to what’s been determined by policymakers as better and more productive sectors such as infrastructure, farmers, or workers in social programs in a down economy with weak growth, it will all be a zero sum game if people are struggling to make ends meet while oil prices rebound.

Lastly, any realized subsidy dividend should consider renewable energy investment, not merely recycled into other forms of fossil fuels.