India’s Foreign Policy Crisis

India’s Foreign Policy Crisis

LONDON: Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh is a busy man these days – on a legacy tour, trying to underscore his credentials as a foreign policy leader of consequence. At home, though, he remains isolated, marginalized by his party, mocked by the opposition and hounded by the national media. Not surprising, therefore, that at the end of his 10-year stint at the helm of Indian politics, he is seeking refuge in foreign lands.

Singh visited the United States in September for the UN General Assembly meeting and then the Association for South-East Asian Nations summit in Brunei, together with a bilateral visit to Indonesia, before heading off again, first to Russia and then to China, two critical states in India’s foreign policy matrix. On the surface, New Delhi’s foreign policy is doing well – major partnerships look steady and various joint declarations proclaim a convergence of interests. But a closer examination suggests that, in the name of multipolar diplomacy and non-alignment, Indian foreign policy is in danger of becoming rudderless, especially with economic decline and political turmoil at home. India’s major relationships are suffering as questions emerge in Washington about India's rise, in Moscow about the gravitation to the West, in the East and Southeast Asia about India as credible balancer – all this emboldens China.

India’s ties with the United States, which Singh bolstered with the signing of the US-India civil nuclear pact, are now flagging. There’s a sense of despondency about the future of India as a potential strategic partner in Washington, unprecedented in the last two decades. The growing differences between the two today are not limited to one or two areas but spread across most areas of bilateral concern. The United States is unhappy that despite valiant efforts to bring India into the nuclear regime the nation has yet to make headway in selling nuclear reactors there. India is concerned by the US immigration changes and forthcoming withdrawal from Afghanistan.

During Singh’s recent meeting with US President Barack Obama, no progress was made on issues apart from strengthening defense cooperation. Singh reiterated concerns stressed during a one-hour meeting with Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, both attending the UN General Assembly meeting in September, over terror emanating from Pakistani soil and the need for Islamabad to rein in elements responsible for the violence. Obama politely thanked Singh “for what has been a consistent interest in improving cooperation between India and Pakistan.” In a separate meeting with Sharif, Obama urged cooperation, pointing out that “billions of dollars have been spent on an arms race… and those resources could be much more profitably invested in education, social welfare programs on both sides of the border.” In turn, Sharif offered “commitment to build a cordial and cooperative relationship with India.” The net result of this triangular diplomacy so far has been unprecedented volatility on the Indo-Pak border with the Pakistani Army violating a ceasefire in operation since 2003 in an attempt to once again internationalize Kashmir issue.

Russia and India, meanwhile, are both keen to emphasize that Pakistan’s bid to rehabilitate Taliban is not an acceptable outcome in the aftermath of a US drawdown but have yet to figure out a way to influence rapidly evolving realities on the ground.

For all the talk of “time-tested” Indo-Russian ties, the two sides feel the pressures of a changing global context. Bilateral trade is struggling to cross the measly $11 billion mark, and Russia’s privileged position as India’s defense supplier of choice is under pressure as India shifts to the purchase of smart weaponry, which Russia is ill-equipped to provide. The Indian military has also been critical of relying too heavily on Russia for defense acquisitions, especially in light of the lengthy dispute over refitting the aircraft carrier Admiral Gorshkov, renamed INS Vikramaditya, supposed to be handed off to India in 2006. New Delhi expected that contracts on the construction of third and fourth nuclear reactors at Kudankulum would be finalized during Singh’s visit, but Russia had liability concerns. For all the brouhaha about US pressures, India’s old friends, Russia and France, also resist entering the Indian civil nuclear power sector.

Russia’s growing closeness with China is also troubling for India as it faces an aggressive China on its borders.

The outcome of Singh’s talks with China was meager. The much touted Border Defence Cooperation Agreement, or BDCA, aimed at curbing border incidents that inflame public passions was his most significant takeaway. Yet the BDCA is more hype than substance as the two sides have already articulated a range of principles and protocols to manage border tensions, most notably in 1993, 1996 and 2005 – all of which seem to have only strengthened China’s position. The visit yielded little on India’s growing trade imbalance with China. On river water disputes, Beijing merely offered to take into account Indian concerns while making its policies and building a series of dams on the Brahmaputra and other rivers that flow into India from Tibet. Sino-Indian ties remain tense.

India’s profile in its own neighborhood has been shrinking rapidly as New Delhi’s inability to shape the evolution of domestic politics in Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka demonstrates. India’s attempt to project its “soft power” in Afghanistan has not yielded the hoped for results. This prompts regional states to question India’s ability to emerge as a balancer in the larger Indo-Pacific. While keen to court India, these states do not see India emerging as a credible actor in their neighborhood any time soon.

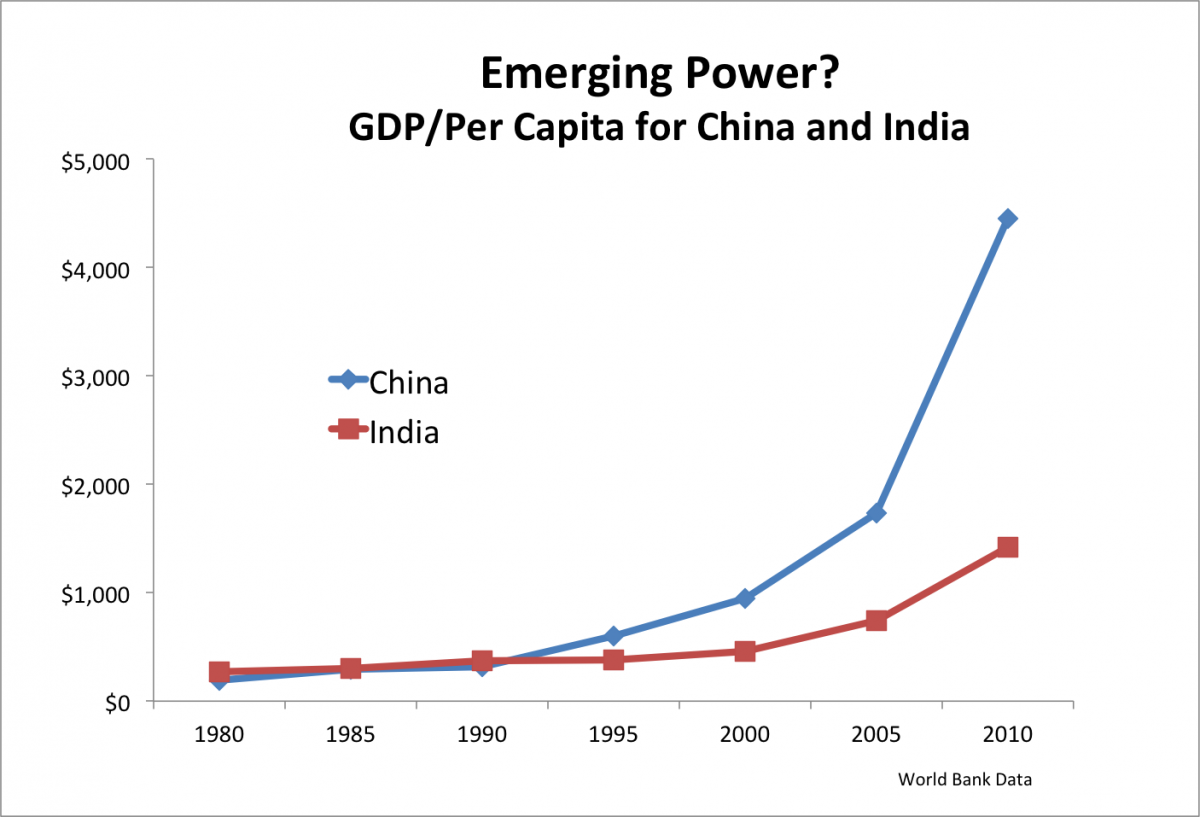

This foreign policy crisis is of India’s own making. Inability to put its own house in order has shattered the notion of India as an emerging global power. In the last five years, the government in New Delhi decimated economic potential, scaring domestic and foreign investors, and making the county hostile to private investment. The peculiar balance of power between the government and Congress Party ensured that Singh – who as finance minister under then Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, opened India’s doors to the outside world – became a party to stifling the Indian economy.

This has had serious implications for Indian foreign policy, and for too long, the Indian policy establishment viewed economic growth as a substitute for grand strategy. The thinking was, Why does India need a foreign policy? They assumed as the Indian economy grew, its weight would automatically resonate in the international system, and they expected to be wooed by major powers.

So once again, the idea of non-alignment was resurrected in the name of grand strategy. The idea that India should be equidistant from China and the US, a critical balancer who could choose sides – touted in the name of “strategic autonomy’” as a unique brand of foreign policy – was laughable at best and disingenuous at worst. Lulled into overconfidence about its own geostrategic significance, it mattered little to Indian policymakers that Chinese economic and military capabilities were far ahead of India’s, and New Delhi on its own had little capacity to balance China.

The last two decades were exceptionally good for Indian foreign policy in that they allowed India to operate in an international environment devoid of major power conflict. Under US predominance, the international system gave New Delhi unprecedented strategic space to pursue economic growth and new strategic partnerships without worrying about costs. After initially taking advantage of this benevolent environment, Indian leadership lulled itself into believing that it would last forever. Where bold choices were needed, all Indian policymakers could offer were a rehash of old ideas. As the system is undergoing changes with relative American decline, India finds itself bereft of economic heft and diplomatic agility. If the Indian story appears less attractive today, then Indian leadership must shoulder most of the blame.

Harsh V. Pant teaches at King’s College, London.