Riots, Language and Britain’s Globalized Underclass

Riots, Language and Britain’s Globalized Underclass

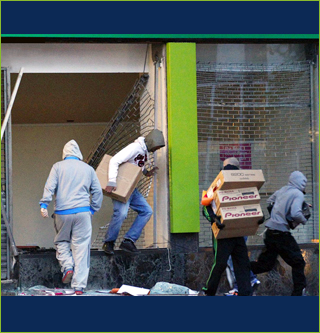

LONDON: In the aftermath of the English riots of August this year, mainstream media analysts pored over the rioters’ language, with special attention to social-media exchanges. There are precedents for this preoccupation with forms of speech as social markers, with British society being acutely class and accent conscious, but on this occasion, something more troubling was going on than the usual fun and games with language and social stereotypes.

A sense that a socially excluded underclass has become worryingly entrenched and that the language spoken by many of the young rioters, largely drawn from London’s marginalized social housing projects, was somehow implicated. The emergence of this dialect, called Multicultural London English, or MLE, by sociolinguists and “Jafaican” by the popular media may offer insights into the accelerating globalization of Britain, the globalization of British English and decreasing social mobility.

In the days after the trouble, many commentators noted the confluence of violent destruction, nihilistic materialism and MLE. The Guardian, for example, presented an array of exhortations to riot culled from texts on Twitter and BlackBerry Messenger, including “the riots have begun ... mandem [a group of boys/young men] pullin out bats n pitbulls everywere. Join in!” and “what ever ends [neighborhoods] your from put your ballys [balaclava, bandana, face covering] on link up and cause havic.”

In a live televised debate, Professor Richard Starkey, specialist in Tudor England and celebrity historian, offered an account of a white underclass that has “become black” in the context of a “violent, destructive and nihilistic gangster culture.” This “blackening” of white youth is most visible, he argued, through the extensive use of a Jamaican patois “intruded” into Britain.

His comments drew a firestorm of criticism from liberal commentators and politicians, with leader of the New Labour opposition party, Ed Miliband, asserting that such comments were “absolutely outrageous” in the 21st century. There were numerous calls for sanctions. But his description of the “patois” as Jamaican was erroneous, for the dialect he referred to is homegrown and British. Yet while Starkey was undeniably wide off the mark on a few points, he articulated the concerns of many and drew attention to a language spoken by many on London streets, one that is a direct consequence of cultural globalization.

As far back as 2001, research by educationalists found that more than 300 languages and dialects were being spoken by children and teenagers in London’s schools, and MLE has emerged from this this exceptionally diverse linguistic environment. More recent research, led by Paul Kerswill at Lancaster University and Jenny Cheshire at Queen Mary, University of London, claims that the new speech form is spoken in more or less the same way by young people of diverse ethnic backgrounds; this is not mere slang, but a dialect, or “multiethnolect,” that emerges out of a multicultural sphere of everyday, shared, lived experiences and negotiations. MLE derives, it’s suggested, from four main sources: Caribbean Creoles, most notably Jamaican – a cornerstone of London street speech for decades and the reason why many non-speakers label it as “black”; former colonial forms of English, such as those of South Asia and West Africa; Cockney, the fading dialect of the London working class; and “learner varieties,” unguided second-language acquisition through friendship groups.

All of this, of course, has reignited a popular British debate about the “dumbing down” of English. But this time round, in the aftermath of riots, the stakes are high. Arguments about the coarsening of language and imprisoning effects of “restricted” language codes are emerging from unlikely sources. For example Lindsay Johns, a self-defined hiphop intellectual, argues that the youths he mentors in south London are trapped – linguistically, educationally, socially – by “ghetto grammar” and cannot “code switch” their way out. He describes a key issue from a linguistic point of view: the inability of some young people to navigate between different languages, dialects or registers of speech. Lindsay’s fear is that young people who cannot do so may be psychologically trapped with a restrictive language that is more for performance than reflection.

The areas of London from which MLE emerged appear, over the last decade or so, to have contracted as neighborhood affiliations intensify and the emergence of gangs represents a new hyper-territorialism at the heart of one of the world’s great global cities. John Pitts’ work on “reluctant gangsters” argues that it is increasingly difficult for young people to opt out of these street-level affiliations. One ray of good news is that these tiny neighborhood identifications are post-racial; the “end” matters in the capital’s patchwork culture more than ethnicity.

But this convergence among young Londoners on MLE could represent a double-restriction of urban space and the mind. And such restrictions are taking place against a backdrop of crisis for disadvantaged youth: The official unemployment rate for British youth is 20 percent, functional illiteracy among teens is at 17 percent, and the country has one of the lowest social mobility rates in Europe, according to an OECD 2010 study.

Many accounts of this crisis do not encompass its many dimensions, constrained as they are by political correctness and liberal orthodoxies around race and racism. A contemporary source of such constraints was the flawed but influential 1999 Macpherson Report on institutional racism, the simplifications and illogicalities of which were matched only by the dogmatic fervor with which the New Labour government implemented its recommendations throughout the 2000s. But Gus John, the Guyanan-born writer and activist who has worked in Afro-Caribbean community empowerment and British education for decades, recently said what white, liberally minded sociolinguists do not say aloud: that much of the dysfunction and pain experienced by the underclass is, to a significant extent, generated from within its own patterns of culture.

John’s voice amounts to a cry of despair that demands recognition of the problem’s true scale, which does not sit well with the conventional wisdom routinely employed, that minorities are passive victims of institutional racism and top-down social injustices. Earlier in the year, before the riots, John called for a “peoples’ inquiry” into murders in the African community, enabled by guns and knives. The role of language and its brutalization was front and center: “No ‘black talk’, street language or slang should contain nonchalant sayings like ‘he was duppied’, meaning that he was shot or stabbed to death; or he ‘got a wig’, meaning that he was shot in the head. All of that represents a measure of brutality and barbarism that dehumanizes not just the perpetrators but the entire community and society.”

Great Britain has a challenge in mainstreaming a globalized, multiethnic underclass, coherent enough to produce a genuine multiculture, but largely immobilized in increasingly territorial and socially dysfunctional neighborhoods. Ending an entrenched, nihilistic youth culture is not easy – and more difficult if those tackling the problem cannot move beyond the narrative that suggests the suffering and social pathologies of the underclass are entirely somebody else’s doing. This would require an end to the condescending pretense that MLE is anything more than a rudimentary, limiting form of street speech. Left unchecked, MLE can only perpetuate the entrapment of its speakers in increasingly primitive “ends.”

Garry Robson is a professor of sociology at the Institute of American Studies and Polish Diaspora, Jagiellonian University, Krakow.