Wrong on Rights

Wrong on Rights

NEW HAVEN: The Bush Administration has jumped into one of the thorniest of legal thickets, and come down on the wrong side. In a case recently argued in California federal court, the White House claims that a 214-year old law that allows foreigners to sue gross human rights violators in US courts threatens foreign policy, endangers corporations, and harms the war on terrorism. The government's position is wrong, unnecessary, and damaging to meaningful efforts to promote corporate responsibility in the US and respect for human rights worldwide. Ironically this would also deny the US the right to try terrorist organizations for their action abroad.

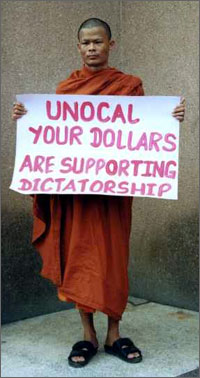

The Administration filed its brief before the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Doe v. Unocal, a lawsuit brought by Burmese citizens, which alleged that the US energy company Unocal had aided and abetted the Burmese military junta's use of forced labor and other human rights abuses during the construction of a gas pipeline. The Clinton Administration vociferously condemned the junta's human rights abuses, which in recent days has led to the brutal arrest of Burma's rightful leader, Nobel Peace Prizewinner Aung San Suu Kyi, and the killing and imprisonment of many of her supporters.

The plaintiffs filed their suit under the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA), passed in 1789, which authorizes aliens to seek civil damages in US courts from defendants who commit "torts in violation of the law of nations," i.e., gross violations of international law. Since 1980, the ATCA has emerged as an important tool of domestic human rights litigation. The plaintiffs cited precedents from seven different federal courts which have upheld the rights of human rights victims residing in the US to recover from state sponsors of terrorism like Iran, indicted war criminals like Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, and officials of Castro's government. In landmark briefs, the Carter and Clinton Administrations had supported the foreign plaintiffs' right to sue gross violators, including nonstate actors, under the ATCA.

In the lawsuit involving Unocal, the lower courts initially ruled that the case could proceed, and the full appeals court just reheard the case, with its decision likely by early fall. The Bush Administration's Justice Department under John Ashcroft had four choices. Like the Clinton Administration, it could have supported the plaintiffs; it could have supported the defendants on case-specific grounds; or it could have declared neutrality (as it did in the Supreme Court's recent Texas sodomy case). Instead the Administration chose a fourth, radical option, urging a position that would wipe out nearly twenty-five years of appellate precedent. The Department dramatically changed its interpretation of the two-hundred year-old statute, now insisting that victims of gross abuse cannot sue under the ATCA, even if they could prove that defendants shared responsibility for the abuses, because the claimed abuses occur outside of the United States and a ruling against the corporation would endanger American interests in the war on terror.

The administration's position is wrong, as both law and foreign policy. Only seven years after the ATCA first became law, the then-Attorney General opined that "there can be no doubt" that the law affords aliens injured by torts committed in violation of the law of nations "a remedy by a civil suit in the courts of the United States." In 1992, Congress reaffirmed the ATCA by enacting a modern statute - the Torture Victim Protection Act - that addresses the same concerns. The Administration's approach would virtually repeal these laws by granting immunity to all human rights abusers, whether official or corporate, so long as they commit their violations abroad. Moreover, the Administration's approach harms, not helps, the war against terrorism, by equally immunizing from suit Al Qaeda, other terrorist groups like Hamas or Hizbollah, and state sponsors of terrorism.

Nor is the government's approach necessary to protect US corporations against frivolous ATCA suits. More than half a century ago, the Nuremberg Tribunal held private German industrialists criminally liable for their support of the Holocaust. US courts are fully capable of dismissing frivolous lawsuits and do so routinely. Since 1993, there have been more than twenty ATCA cases against private corporations, some of which have been dismissed and none of which has yet resulted in a final judgment against a US company. Indeed, the federal courts of appeals have unanimously held that corporations can be sued under the ATCA, but only so long as plaintiffs can meet the high threshold of proving that the defendants knowingly committed or collaborated in the commission of crimes against humanity. If adopted, the Administration's position would perversely push similar lawsuits against our companies into foreign courts, where they will lack the protections of US law.

If this Administration is seriously committed to promoting corporate responsibility in human rights, it should not attack the ATCA in our courts or call for congressional tinkering, as some business groups suggest. Rather, it should support an international treaty on what constitutes unacceptable corporate "aiding and abetting" of governmental human rights violations. Such a treaty would give valuable guidance to the courts and to corporations about what types of overseas conduct are impermissible. The last administration helped negotiate a similar private-public deal in which foreign corporations that had profited from the Holocaust paid survivors billions of dollars in compensation for their losses. Numerous international drafting efforts are currently ongoing to clarify when a corporation illegally aids and abets official human rights abuse. The United States and British Governments are already developing common standards to clarify when a corporation illegally aids and abets official human rights abuse and work is proceeding on an international convention under OECD auspices. The Fair Labor Association has created both an industry code and a transparent monitoring system for companies in the apparel industry. In 2000, several major oil companies and then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright announced principles to regulate human rights abuses for security forces in the extractive industries, and British Petroleum recently announced a human rights code of conduct to govern its operations abroad.

These measures deserve support, but they require a real commitment to multilateral diplomacy and dialogue with responsible corporate leaders. If this Administration cares as much about advancing human rights as it professes, it should put its efforts into developing such standards and encouraging responsible companies to meet them, not attacking a venerable law that has been used to call terrorists and genuine corporate abusers to account.

Harold Hongju Koh, Professor of International Law at Yale University, served as Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor in the Clinton Administration.