Europe in Disarray – Part II

Europe in Disarray – Part II

PARIS: For more than half a century, European life has been charmed – peaceful, prosperous, and able to settle its differences as it advanced towards greater unity. Now, the double blow of the rejection of the proposed constitution and the collapse of European Union budget talks offer a salutary reminder that the past is no longer enough. Europe must choose between the prospects offered by a volatile market-driven economy and the comfort of a contracting social-welfare economy.

Backroom deals that kept the European project together have reached their limits. The gulf between differing economic and social goals is so wide that national leaders can no longer paper them over by evoking a broader common purpose. Europe faces a challenge for which, in its present state, it may not be prepared.

The collapse of budget talks in Brussels last weekend revealed the growing strength of national sentiment in major member states. Across the continent, countries are turning inward, particularly in France, where the recent tendency has been to reject change.

With politicians engaged in a heated blame game, Europe's claim to represent a new form of internationalism is in tatters. The collapse of a common will has hurt the steadily falling euro, as traders worry that the prevalent political atmosphere – to which the currency is, supposedly, immune – may continue to pull down its value. The European Commission's modernizing agenda is severely jeopardized. The prospect of a unified market in services, to complement the single market for goods, is a lost cause. Ten new member states, mainly from formerly communist Europe, look on askance, fearing for aid promised to them. Euro-skeptics of right and left rejoice.

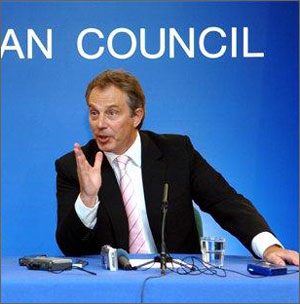

This does not, however, signal the end of European Union. The EU will continue functioning, even if decision-making among the two-dozen nations is cumbersome and potentially disjointed. There will be leaked suggestions of compromise over controversial issues in the weeks ahead, as the protagonists jockey for position. But with British Prime Minister Tony Blair assuming the revolving six-month EU presidency on July 1, the crisis is too deep for the usual last-minute sticking plaster. At stake is the underlying social and political philosophy of the member nations.

Beyond the many, often irrelevant, issues arising from the French and Dutch rejections of the constitution, a basic lesson is apparent: Europe's leaders have lost touch with their people. The EU has become the scapegoat for concerns that are not its doing. In the Netherlands, voters worried about the economy, government spending cuts, and immigration. In France, high unemployment, hostility towards the political establishment, and fear of low-cost competition from new EU states won a majority for the No vote.

President Chirac's support is at a record low – below 30 percent in opinion polls – and his refusal at the budget talks to consider any reduction in French farming subsidies has done him no good. Instead of hailing him as a hero upon his return, the French press labeled him a failure – particularly damaging since foreign policy has been one of his strong points.

The weakness of leadership is reflected across the Rhine. A weak economy, high unemployment, and an unpopular – if much-needed – reform program have forced Chancellor Gerhard Schröder to call an early federal election, in which the polls predict a loss to the Christian Democrat Union (CDU). His probable successor, CDU leader Angela Merkel, may take a less rosy view of the French leader, who has two remaining years in his term. Behind the electioneering screen, Merkel is thought to be much more ready than Chirac to envisage a gradual move away from the post-war welfare state consensus. In this sense, she may be more in tune with the Chirac's probable successor, Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy, whose path to power Chirac is intent on blocking – if he can.

Meanwhile, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, fighting to hold together his coalition government, faces a tough battle in national elections next year against a revived left, which did well in recent regional polls. His economic policies have not worked, and many suspect that he uses legislation to defend himself from corruption allegations. In the end, the election will come down to a vote of confidence, or no-confidence, in the media mogul turned prime minister. Of the four main EU players, Blair stands out, if only because – despite falling levels of public trust – he won a third term in the May general election.

Now, as he takes over the EU presidency, Blair wants to spread the gospel of economic and structural reform to rescue the continent from its economic doldrums. In the Brussels discussions, he underscored the need for a fundamental re-assessment, starting with agricultural policy, which soaks up 40 percent of EU spending. Originally allocated by agreement between national governments, this spending plan parallels the original Common Market deal between French farming and German industry. Better, says Blair, to devote less to farmers, and more to research and development, encouraging new technologies to help Europe compete in a globalized world.

Blair trusts that Merkel – and then Sarkozy – would more likely prove to be collaborators than Schröder or Chirac. He also hopes for backing from new EU states in the East – though his rejection of their proposed compromise soured relations.

For all his thirst for change, the British PM faces an uphill battle. The relationship between London and Paris is at a new low. Desperately seeking support at home, Chirac cannot compromise on agriculture; farmers voted heavily against the constitution, and any decrease in subsidies would trigger potentially violent demonstrations.

Beyond these concerns, deeper currents are at work. Paris and Berlin want to retain their leadership roles, rather than letting Blair bring to the EU his reformist zeal. France and Germany insist that English-style "liberalism" – the market – would destroy social and economic systems their countries hold dear. The chairman of Schröder's Social Democratic Party speaks menacingly of "locust" investment funds sucking the lifeblood from German firms, while Chirac insists he will protect the French from "le liberalism anglo-saxon."

Blair must walk a fine line. At Brussels, he rejected any tampering with the US$5.5 billion (€4.6 billion) compensation Britain receives for its contribution to the overall EU budget, mainly for agriculture. His unyielding position, reminiscent of Margaret Thatcher, may work well at home, but it scares new member states, which risk seeing their aid programs blocked as a result of the budget breakdown. Also, it makes it all too easy for Chirac and Schröder to portray Britain as the EU "bad boy" – at the very time when Blair must paint himself in the most positive possible colors.

So, even if the need for change in Europe is widely accepted, there is little agreement on its shape. For France and Germany, the future is in the past, returning to a supposed golden age when Europe's economy functioned better, when the elite ruled unchallenged, and when governments could afford extensive welfare systems. For Britain, it lies in a leaner, deregulated continent, where a social safety net exists in a market-driven economy. Grave as the referendum votes and the budget collapse were, Europe faces even more fundamental choices. The question is whether it has the will to even address the issues.

Jonathan Fenby is author of On the Brink, the Trouble with France (Abacus), and Editorial Director of the predictive news service, earlywarning.com.