Europe’s Next Immigration Crisis

Europe’s Next Immigration Crisis

ATHENS: Although a wave of race riots in France caught the world’s attention in late 2005, another immigration problem is emerging in Europe that has yet to make headlines. Around the periphery of Europe – in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and along the Mediterranean -- a new group of countries is playing host to immigrants from foreign shores. The question arises: Will these new destination countries follow the path of alienation and intolerance forged by Western Europe during the last forty years?

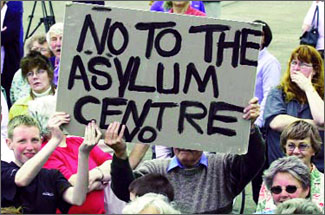

The last decade has been a dangerous period for many of Western Europe’s new arrivals in Germany, England and France. We’ve heard about the fire bombings of immigrant hostels, racially motivated attacks in small German towns, immigrant riots on the streets of Britain and so on. Anti-immigrant feelings have also manifested themselves in semi-official expression with the election, or near election, of right-wing demagogues like Jörg Haider in Austria, Jean-Marie Le Pen in France or Pym Fortuyn in the Netherlands.

In each case, a combination of three factors helps stoke anti-immigrant feelings: first, the total number of immigrants; second, the pace at which they come; and third, a sense of economic insecurity in the local population.

Not surprisingly, the regions with the highest percentage of foreign-born residents are the most developed, namely North America (13 percent) and Europe (7.7 percent) – as people move where there is economic opportunity. And the gap between rich and poor countries is growing ever wider. According to the United Nations, in 1913 the richest countries on earth were 10 times wealthier than the poorest. In 2000, the difference was 71 times.

And the UN says that the number of migrants around the world is at an all-time high – there are almost 200 million international immigrants, more than double the 84 million of 30 years ago. Relative to total world population, one out of every 35 persons on earth is an international migrant. This means that international immigration is a fact of life and it is growing.

But for many of the new destination countries in Europe, the transformation has been profound and sudden. Take Greece, for example: Until 20 years ago, the country was one of the most ethnically homogenous in Europe, with as much as 98 percent of the population identified as Greek. But after a 15-year immigration boom, one out of every ten residents in Greece -- and almost one in five in the center of Athens – is now foreign born. The vast majority came from neighboring Albania, but there are growing numbers of West Africans, Chinese, Pakistanis and Arabs too, and almost all are illegal residents. Likewise in Italy, over the last 20 years the number of foreign-born legal residents has grown from around 300,000 to more than 2 million. In Spain, which has received waves of immigrants from North Africa, there are some 4 million legal and illegal newcomers, combined making up about 10 percent of the population.

The pace and the number of newcomers have started to stir anti-immigrant feelings. In Greece early last autumn, one of the stranger political gatherings of Europe passed almost unnoticed by the outside world on the streets of Athens. Some 150 or so right-wing youth – purportedly from Spain, Italy, France, Germany and Greece – met in the center of the city in the first ever pan-European meeting of racist, anti-immigrant groups. Polls throughout Europe have shown that youth, often competing with immigrants for scarce jobs, are usually the most opposed to immigration. Last year’s meeting itself was a dud, attracting far fewer participants than hoped for by the organizers, the Greek extreme right group Golden Dawn. But that the meeting took place at all is remarkable.

Meanwhile, in parts of Eastern Europe, the extreme right is experiencing its own small renaissance. In Poland, right-wing extremist groups have gained influence since last year’s elections. And in November, anti-immigrant fascist groups marched through the center of Moscow. Although the immigrant populations in Russia and Poland remain small for now, the continuing shock of 15 years of post-Communist economic adjustment has manifested itself in signs of intolerance. In Russia, for example, hate crimes have been rising steadily for several years.

The question is, What is the tipping point? When do attitudes in new “destination” countries go from acceptance to intolerance?

“Some would argue that there is a threshold in Europe, say, around 10 percent of the population. And above that threshold, intolerance gets out of control. But more important than the total size of the population is the rate of increase and under what conditions, how fast it has happened,” says Anna Triandafyllidou, a senior research fellow focusing on immigration at Eliamep, a Greek think tank. “As far as patterns go, you might say, although it’s a bit of simplification, that northern and western Europe were the first hosts and faced the first problems. And now central and eastern Europe are following suit.”

Take a look at racist attacks in Germany, where there have been immigrants for decades – most notably Turks and Greeks who were taken in as guest workers from the 1960s onward to work in the country’s resurgent industries. But the worst forms of extremist violence took place throughout the 1990s. That’s when the number of hate crimes rose steadily, peaking at 14,724 in 2001. Those attacks coincided with the economic downturn that followed German reunification and during a rising wave of immigration – between 1991 and 2003 some 14.2 million immigrants arrived in Germany.

When there are too few jobs, either nationally or within certain regions, antagonism between locals and newcomers grows. Again, looking at the case in Germany, a disproportionate number of racist incidents take place each year in the “east,” where unemployment ranges around 15 percent, double the rate in the western part of the country. That is despite the fact that eastern Germany has relatively few immigrants.

Throughout Western Europe, the pattern is the same. In 2001 the UK witnessed a summer of racial violence in the towns of Bradford, Oldham and Burnley. All of them are located in the economically depressed north of England and all had seen a relatively recent influx in new immigrants. In France, there has been a striking rise in the number of racial attacks on Corsica against the island’s mainly Moroccan immigrant community. It is worth noting that Corsica is by far the poorest region of France, with the second highest ratio of immigrants – some 10 percent of the population. The highest ratio is found in the city of Paris and the surrounding suburbs, the epicenter of the riots in 2005.

So even though last autumn’s right-wing gathering in Athens proved to be more ridiculous than riotous, one must wonder if it is a sign of things to come. What would it take for the opposition to gather steam, or worse, break into fire bombings and street attacks? As a whole, Europe still has not squarely confronted the issue of immigration. Now another chapter of intolerance looms as the poorer countries of Europe follow the path of their richer neighbors.

Alkman Granitsas is a freelance journalist based in Athens.