US Election and the World – Part I

US Election and the World – Part I

PARIS: The day after the US re-election of George W. Bush, Europe woke up with a hangover, resigned to the fact that the Bush II show will go on just like the Bush I did, with or without the Europeans. The show must go on. Whether it likes the play, the actors, the director or not, Europe has no choice: As the British daily, The Independent, wrote, "America has voted for Bush, and the world must live with the consequences."

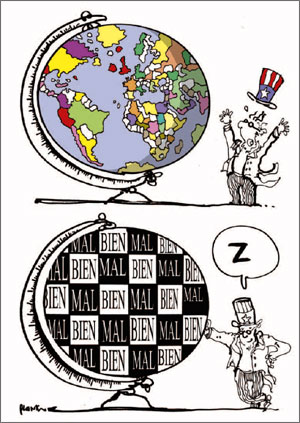

This resignation is tinged with apprehension that the quarrelling-old-couple Europe-US relationship might be headed for the rocks. And, though most leaders have expressed hope for reconciliation and improved cooperation, Bush's leadership has greatly alienated much of the European public and left European leaders at a loss for common ground with their long-time ally.

Though many hope that George W. Bush's second term will be more moderate than the first, Europe remains confused about how to respond to US proposals. In the last four years, pro-Bush opinions in Europe have been dismissed as overly compliant with Washington's whims. Meanwhile, anti-Bush stances have been rejected, as in the case of French President Jacques Chirac, who almost always said no to Washington.

Except for the support from leaders like Britain's Tony Blair, Italy's Silvio Berlusconi, and Russia's Valdimir Putin, the Republican tidal wave baffles and frightens most European politicians. The European Union is proud of having shed extremism, exacerbated nationalism, and religious fundamentalism: The notion of the world divided between Good and Evil is perceived with dread, and religious practice is slowly fading away. Nothing underlines the cultural gulf better than the recent European Parliament rejection of a highly religious Italian commissioner candidate. He had publicly condemned homosexuality as a sin and stated that women should stay at home and bear children. Having rejected such views in their midst, European politicians find the influence of conservative religion in American politics extremely difficult to grasp.

It is obvious that Europe has deeply misunderstood the wide appeal of conservatism in the United States. Europe's increasingly secular societies find it hard to comprehend how the Middle East and America could be the main regions where religion is gaining ground. Many preferred to think that religious fervor was limited to a loony right. They believed that the Democrats, who are closer to the European mainstream mindset, would have mass appeal in the United States. They underrated both the appeal of "values" to American voters and the divisive nature of issues like abortion and gay marriage.

One would be hard-pressed to find many European personalities satisfied with the outcome of the American election. Even before the vote, a vast majority expressed their support for John Kerry, and most of the European press – including The Economist – had endorsed the Democratic candidate. After the vote, even the ultra-liberal head of the French employers' movement expressed great personal sympathy for Kerry. In France, few politicians outside the far right supported Bush. These anti-Bush sentiments were widespread and mainstream, and thus deeply distinct from the Cold War era anti-American feeling which was limited to left wingers and nationalists.

Europe's leaders nevertheless recognize the importance of maintaining good US relations. European leaders are currently engaging in damage limitation exercises, trying to avoid a worsening of transatlantic relations and hoping, on the contrary, for improvements, even if modest. Indeed, Bush's lack of popular support in France didn't stop President Jacques Chirac from sending his "Dear George" a congratulatory message expressing his "very cordial friendship." He also articulated in this letter his hopes that Bush's "second mandate could be the occasion to strengthen Franco-American friendship," and provide the opportunity to continue "the common fight against terrorism." Today's challenges, he added, cannot be overcome without a "tight transatlantic partnership."

The tone of France's response has not been entirely conciliatory, however. Chirac's Foreign Minister warned Americans that they cannot aspire "to build and lead the world alone." And, even if Paris wishes to engage Washington on areas of common interest and change the tone of bilateral relations, it is still highly unlikely that France will send troops to Iraq or consent to direct NATO involvement in the country's reconstruction. As Jean-Marie Colombani, publisher of the French daily Le Monde, noted, the United States and Europe are now "a world apart."

This growing gulf means that while attempting to define its relationship with the United States, France must also consider the position of its major European partner, Germany, which wishes to improve relations with Washington. Chancellor Gerhard Schröder expressed this desire as in "the interest of the US, of Germany, and of Europe." But this did not stop major German newspapers, like the moderate left Sueddeutsche Zeitung or the conservative Frankfürter Allgemeine Zeitung, from expressing their worry of a "war of cultures" across the Atlantic. This concern is shared by many media throughout the continent, including the UK, and is the reason why Europe is faced with a major challenge: to build itself into a world power. Denis MacShane, Britain's minister for European affairs, stressed this, suggesting that Europe should stop obsessing over America and concentrate instead on building a strong Europe to partner with the United States.

Britain also hopes for smoothed European-US relations. Prime Minister Tony Blair wants to use his position as President Bush's closest partner in the war in Iraq to bridge the gap between European leaders and the US administration. He also hopes that the United States will more actively seek a political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – a hope shared by all Europeans, even if they lack Downing Street's optimism. PLO Chairman Yassir Arafat's failing health will certainly exacerbate Europe's concern over the situation. Blair knows how unpopular his pro-American policy is, including among many Labour MPs. And, as columnist Peter Riddell wrote in "The Times," this is his big chance to show he's no puddle."

Hope thus remains among European leaders that, as the dust settles – and if the Bush administration doesn't display too much disdain – relations could yet improve. The appointment of the new US Secretary of State will be a good indication of the White House's attitude towards the rest of the world, as Colin Powell was widely regarded as the soft side of the administration.

If the United States does not meet certain conditions, many believe that the Euro-American parting of ways might be irreversible. The future of the European-American alliance is thus at a potentially fatal juncture. The former head of the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London, François Heisbourg maintains that the gap between the two is so wide and the understanding so lacking that "the process of slow disintegration of the Atlantic Alliance will go on."

French academic Patrick Higonnet, who teaches history in the States, described the situation to Le Monde before the election: "We are living through a great turning in the history of this old couple which was formed between America and Europe, quarrelling but nevertheless lasting. Today, a divorce seems to me unavoidable. It will be a friendly one if Kerry wins, a bitter one if the election turns sour."

The Bush administration thus has one last chance for reconciliation with its most enduring partner. But both parties must really want it.

Patrice de Beer is an editor with Le Monde.