Aramco Attack Exposes Saudi Vulnerabilities

Aramco Attack Exposes Saudi Vulnerabilities

CANTON, CHINA: The recent drone attacks by unknown actors of Saudi Arabia’s Aramco Abqaiq oil processing facility on September 15 highlights the company’s extraordinary significance to the world’s energy economy. The attack is expected to lop off 5 percent of the world’s oil capacity in the near term and could further derail a long delayed Saudi Aramco initial public offering that had once been expected in late 2019.

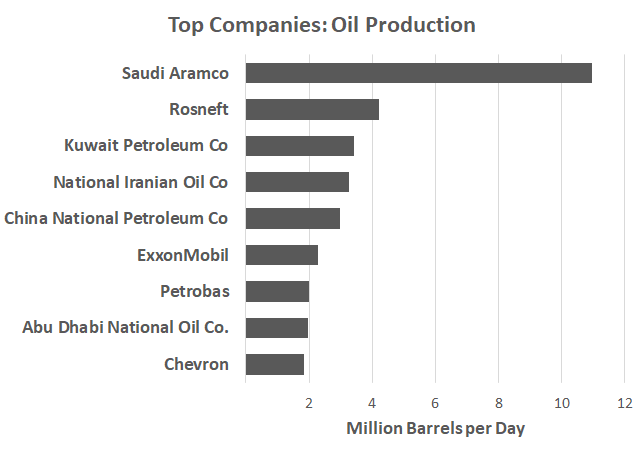

Saudi Aramco is simply the world’s most profitable company, its 2018 profits exceeding $111 billion, more than double the $53 billion of distant second-place competitor Apple. To put this in perspective, the all-time record profits overshadow all other Saudi companies combined and is more than the profits of Google, Facebook, JP Morgan and Exxon combined. Saudi Aramco’s profits are partly due to its low oil production costs, about $3 per barrel, against a world average of nearly $30 a barrel, but high taxes supporting the Saudi economy eat into that profitability.

Saudi Aramco caught the attention of global investors in 2016 by proposing an initial public offering. As described by former Saudi Energy Minister Khalid al-Falih, the IPO would be for an estimated 5 percent equity float of the company and the biggest stock market IPO in history, with an estimated valuation of $2 trillion and expected to raise upwards of $100 billion for Saudi Arabia. Officially, the IPO was postponed, not cancelled, to acquire a 70 percent stake in Saudi petrochemical company SABIC. Postponement was a relief for the many international banks and legal advisers who stood to make up $200 million on the IPO flotation.

Higher oil prices may have reduced capital need and softened the blow to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 plan to reduce oil dependency. At any rate, the float value of 5 percent equity to private ownership still ensures near total Saudi royal control of this company described as a “crown jewel.”

Saudi Arabia continuously endures an economic diversification problem underscored by volatile oil prices, of which this attack amplifies. Any shortfall in oil revenues wreaks havoc in economies over-reliant on oil. The Saudi phenomenon of great wealth and voluntary “educated unemployment” persists to this day. Unlike other countries, where youth travel abroad for education in mostly Western countries, many with the aspiration to stay, Saudi youth long to return home for high-paying, white-collar, government-sponsored jobs that their oil economy provides. This trend is costly, and entrepreneurship along with lower-level job entry suffers. Saudi Arabia must import foreigners to do the heavy lifting.

Saudi Arabia has multiple ways to achieve diversification: upgrading oil and gas sectors to produce more value-added products, such as plastics and special fuels; allowing private development of largely untapped natural mineral abundance in vast Saudi deserts; encouraging more entrepreneurship opportunities among small- and medium-sized businesses; reducing regulation; and accommodating the growing impact of women in the workforce. Diversification must also prioritize newly emerging world trade patterns, especially Asian markets, and the digital economy. Saudi Arabia is trying to do this with the $500 billion creation of its digital city, Neom, modeled after Singapore, but can-do and know-how matter more than costly facilities.

In The Saudi Arabian Economy, Mohamed Ramady writes extensively about the need for Saudi Arabia to diversify its oil and gas economy and implications on not doing so for its people and competitiveness. Peaking oil reserves drive this need for economic diversification, particularly in the Ghawar field of eastern Saudi Arabia, which pumps out more than 3.8 million barrels of oil a day. While still an incredible production feat, accounting for one in every eight barrels of the daily world crude oil supply, the output is significantly below the 5 million barrels a day that the oil markets held for several years, considering more than 260 billion barrels of oil still in reserve. Additionally, Saudi Aramco pegs much of its further development on large-scale shale gas production, in other words a plan for more addiction to the fossil fuel model, not less.

Nonetheless, the markets simply do not trust Saudi commitment to diversification and a Saudi future beyond oil. Despite the 2014 dip in world crude prices that disrupted Saudi balance sheets, offering a catalyst to diversify, the rebound in oil prices since 2017 not only put the IPO on hold, but renewed Saudi Aramco interest in increased production and exploration activities abroad. A bond issue in April, attracting $100 billion in demand, gave reason to pause in any rush to privatization. With money rushing in, Saudi Arabia has no need to listen to nagging boards of foreign directors and shareholders.

Two critical implications of the bond offering highlight money over substance:

Climate change: The world continues to be addicted to oil. Even with renewables, caseload power for cars, trucks, ships and planes will be fossil fuels well into the future. Green energy such as vehicles powered by electricity and batteries has only a small market share and only in wealthy countries, mostly in Northern Europe and developed Asia including Singapore, South Korea and Japan. BP’s 2018 world energy report states that oil use will grow, in particular in developing countries through 2040, even if renewables do increase “off the charts.” The markets recognize this, which is no doubt why the Saudi Aramco bond issue was oversubscribed: Payments are stable, put forward by a profitable state-controlled company.

Human rights: US President Donald Trump reaffirmed that human-rights issues carry low priority when he proclaimed that the Saudi Arabia buys too many weapons, about $450 billion worth, from the United States, adding that one individual’s death – namely, the October 2018 botched murder of Washington Post writer Jamal Khashoggi in a Saudi consulate in Istanbul – could not jeopardize those sales. Other human rights issues shoved under the rug include Saudi Arabia’s proxy war against Iran in Yemen against Houthi separatists, with atrocities against civilians by Saudi Arabia forces documented. Empowerment of women, beyond driving cars, remains a concern. Saudi Arabia is highly patriarchal and relies on immense monetary clout in diplomacy to remain that way.

The Saudi bonds slid in value even before the recent troubles including sabotaged tankers. Saudi Arabia is eager to soothe global markets and avoid supply disruptions. Avoiding a major recession or war would coincide with Trump administration goals before the 2020 US presidential election. Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, appointed days before the attack, suggests the damage will be repaired within weeks and the IPO will proceed as planned. Houthis in Yemen claimed credit for the attack, but the United States and Saudi Arabia blame Iran. Iran denies responsibility. Regardless of the attack's source, analysts question Saudi and industry security capabilities in the highly monitored Persian Gulf region. Saudi Arabia, despite a decrease from recent years, spends more than 8 percent of its budget on defense, ranking among the top five countries in the world with military expenditures, while Global Fire Index ranks the Saudi military as 25th.

Economic diversification is crucial to be competitive in today’s knowledge-driven digital world. Huge profits from Saudi Aramco and its various subsidiaries may prevent Saudi Arabia from achieving this goal. Petro states, from Nigeria to Venezuela to Malaysia, struggle to wean themselves off the addiction to dollarized revenues for a commodity and immense wealth when prices are high. The attacks have only accented the volatility of oil markets, driving prices higher by highlighting the instability in the Middle East and the fact that there is no real alternative to Saudi oil production when the chips are down. For now, the attacks may force a necessary rethink on many Saudi plans and possibly even de-escalation of tensions with Iran and Yemen.

Will Hickey is a Visiting ASEAN Professor with Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Canton, China. He is also author of Energy and Human Resource Development in Developing Countries: Towards Effective Localization, Macmillan, 2017.