Energy Transition: Coal as the Canary

Energy Transition: Coal as the Canary

AUSTIN, TEXAS: The Covid-19 pandemic has presented a range of pressing economic challenges including unemployment, lost wages and volatile stock markets. Stalled economic activity has also temporarily reduced energy demand and pollution levels around the world. While the coronavirus creates acute, emergency needs for many households and communities, the kinds of social safety net measures that can cushion the impact in this current crisis have similarities to those needed for longer-term clean energy transitions. Recovery from this pandemic may offer opportunities to recover with a lower-carbon and more equitable economy.

Even before the pandemic, the global energy landscape was already changing dramatically, with the rise of shale gas and renewables leading to major shifts in energy markets. Similar to previous technological revolutions, a clean energy transition could have significant consequences for workers and local economies. For example, when societies transitioned from the horse-and-buggy to the automobile, jobs for blacksmiths and stables all but vanished, but new industries, social structures and jobs emerged. The same is true today.

.png)

Over the past 10 years, natural gas and renewables have reshaped the electricity landscape in the United States, leading to coal’s rapid decline. A decade ago, coal’s continued growth seemed inevitable – it was still the dominant source of electricity in the United States and the appetite in rapidly industrializing countries seemed insatiable. Today, coal’s future in the United States is bleak, and pressure grows in other countries to phase out coal to address air pollution and cut carbon emissions.

In the United States, power generation from coal has been eclipsed by natural gas and will likely be surpassed by renewables in coming years. In 2009, coal provided over 45 percent of US electricity demand, but by 2019 it was less than 28 percent. Five US coal companies filed for bankruptcy in 2019 alone.

The transportation sector is also ripe for change. Though electric vehicles still constitute less than 1 percent of all US vehicles, businesses and governments are leading the way in electrifying fleets. If climate change drives new policies, as expected, fossil fuel-based industries will inevitably be affected. Cement, steel and plastics industries also brace for transition, beginning to research and invest in low carbon solutions.

These changes raise questions about what obligations governments have to their citizens. How can governments support workers and communities so that the energy transition does not make them permanently worse off? How can governments provide income support and invest in training and skills to reemploy people in emerging sectors and attract new businesses?

Arguments for a “just transition” suggest that the clean energy transition must attend to equity and justice for those whose livelihoods depend upon fossil fuels and support vulnerable communities that lack access to energy or suffer from pollution. Numerous communities in the top coal producers of China, India, the United States and Australia rely on coal revenues and taxes. For example, before it was recently shuttered, the Navajo generating station, a coal-fired complex near Arizona, brought the Native American community $40 million per year to the otherwise impoverished Navajo Nation. Other communities are just as reliant on oil and natural gas for budgets and jobs. Just transition centers the considerations of communities dependent on fossil fuels and the needs of underserved and vulnerable communities.

To prevail in political debates about a clean energy transition, advocates must establish support mechanisms including salary, pension, health care and job retraining. In the US context, many of the contenders for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination embraced just transition policies in their campaign platforms, but these concerns extend beyond a single political party.

In December 2019, Congress rescued the pensions of nearly 100,000 retired coal miners, authorizing the US Treasury to transfer as much as $750 million a year to such pension funds. Bankruptcies in the sector left few to no companies contributing to the funds. In Colorado, a recent bill, HB 1314, created a new institution called the “Just Transition Office,” to focus on the impact on coal plant workers and mine closures. Abrupt closures of two Wyoming coalmines in 2019 led to calls for emulating Colorado.

Other countries like Spain and Germany are also grappling with how to support communities in the transition away from coal. While the Trump administration fights a futile battle to revive the coal sector, the Merkel government in Germany negotiated an accelerated $44 billion coal phase-out plan, including $4.8 billion in compensation for coal producers over the next 15 years as well as funding for clean-energy research institutes and worker retraining.

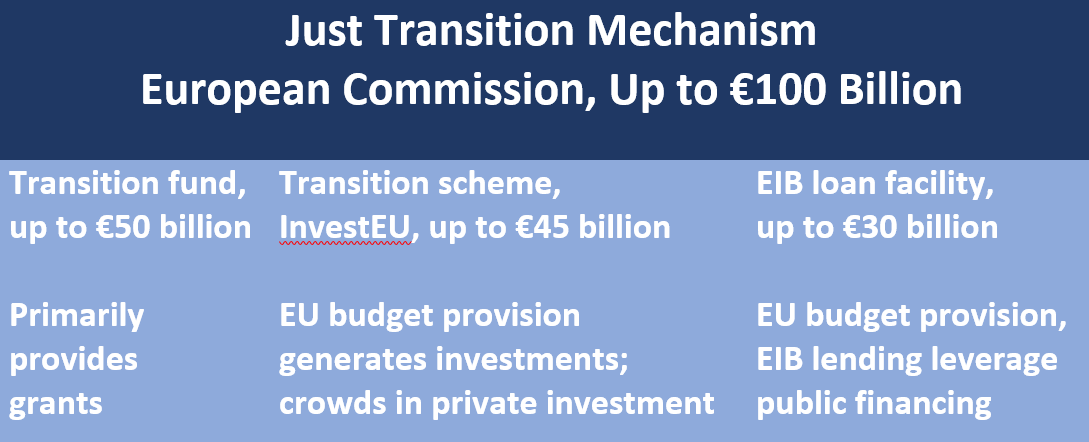

In January 2020, the European Commission issued a proposal for a Just Transition Mechanism to mobilize €100 billion, about US$107 billion, between 2021 and 2027 in supporting regions struggling with the transition. The proposal includes additional funding to the EU’s existing Multiannual Financial Framework, direction of InvestEU funding to transition projects and a public-sector loan facility at the European Investment Bank – all intended to support displaced workers, revitalize local areas and invest in land restoration with emphasis on coal-intensive regions.

International organizations like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and forums such as the climate negotiations offer recommendations for managing these transitions, including income support, local economic development programs in affected communities, job retraining programs, sharing best practices, research and development programs to foster technological adjustment, and sustained attention to indigenous and minority populations.

The coal sector is the canary in the transition to clean energy, and other sectors can also anticipate disruptive technological changes – utilities, engine and turbine manufacturers, auto parts suppliers, oil and gas, steel, cement and more. A lack of policy certainty as well as state and regional entities to assist with energy-transition planning add to the challenges. The proposals for a just transition are not simply about making workers or communities whole in the face of disruptive change, but preparing for a vibrant and equitable 21st century clean-energy economy.

The ability of states like China to capitalize on investments in clean energy to command large market shares in clean technologies raises questions about whether the United States should have an industrial strategy. For example, China invested a decade ago in photovoltaic manufacturing, dropping costs of solar panels by 80 percent. Today China is the dominant supplier of these technologies to global markets. A similar pattern is in process for batteries and electric vehicles, with China already establishing a dominant 73 percent of lithium-ion battery production capacity.

Strong industrial policies can send clear signals to market actors and reward investment in renewables, energy efficiency technologies, mitigation strategies as well as forward-looking innovation in carbon capture, advanced nuclear technologies and next-generation solar capability. Countries that remain overwhelmingly reliant on legacy energy technologies risk exposing workers and communities to large losses in sectors that become obsolete.

Energy transitions inevitably create winners and losers. Establishing dedicated institutions, financial mechanisms and thoughtful planning is the only viable route towards ensuring a transition that is not only clean but also just. The United States would be well served to make long-term investments, highlighting sources of revenue, such as reversing Trump era tax cuts for the wealthy, versus the costs of doing nothing. Otherwise, the United States runs the risk of propping up the last vestiges of the 20th-century energy economy and ceding leadership of the energy transition to others.

Recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic will eventually lead to a pulse of economic activity and higher pollution levels, but there will also be opportunity once this crisis subsides to support a low-carbon and more equitable economy. The impact of the energy transition on the vibrancy of local communities will be a key metric of success.

Joshua Busby is associate professor with the LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas-Austin. Morgan D. Bazilian is director of the Payne Institute, Colorado School of Mines. Dustin Mulvaney is associate professor of Environmental Studies at San Jose State University.

Comments

Splendid article, neatly encapsulating the challenges and opportunities ahead for - albeit centred on the USA circumstance - the energy supply industry globally. During my own studies of the evolving situation, I have become increasingly convinced of the pivotal character of 'climate justice' in the effort to achieve a successful global energy supply transition: an aspect that I suspect may still be lost on observers of a purely technocratic mindset, as I have been in the past.

We in the UK also have our ghost towns - and harrowing it is to visit them: some ex-coal mining communities, others legacies of other dead or dying industries. It is nothing short of infuriating that similar 'capitalist sentiment' to that which spawned and nurtured those communities is so glaringly absent at their hour of greatest need - a dignified demise, and regeneration in a new form, fit for the next surge of enterprise.