The Future of Migration - Part Two

The Future of Migration - Part Two

CAMBRIDGE, USA: As economic, demographic, and technological forces propel another mass migration ( See "The Future of Migration - Part One"), the anti-immigration sentiments of rich receiving countries are preventing this influx.

Technically, migration is prevented by people with guns. It is the threat of violence that prevents people from crossing borders to take advantage of the economic opportunities. In nearly all industrialized countries (the preferred destinations of migrants) the people with guns are employed by a democratic government, a government which usually represents the preferences of its citizens. Thus, the primary reason there is not more migration is that the citizens of the industrialized world don't want it.

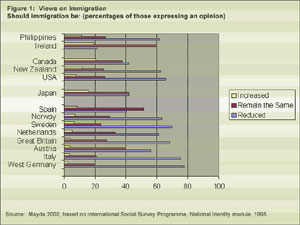

This reality was reflected by the International Social Survey conducted in 1995 (see Figure 1). The survey asked people in many different countries if they were in favor or against higher levels of immigration. In no place in Europe was support for any additional migration higher than 10 percent. Moreover, those that favored reductions in the level of migration were an absolute majority in almost every Western European country and composed the largest category everywhere else.

These statistics have likely become more pronounced in the aftermath of 9/11, since there has been an understandable backlash against "lax" control of borders. It was reported that almost two-thirds of Americans were in favor of halting all entry of any kind from countries suspected of harboring terrorists.

Thus, advocating a substantially greater flow of immigration appears to be an electoral loser. The widespread view is that it is simply impossible to drastically increase labor flow above the current levels, and hence it is futile to even discuss the issue.

It is interesting that a large strand of "rights based" movements have been about eliminating differences in offering employment based on arbitrary differences - in race, in gender. Yet the largest differences in the world's job market - between workers in "have" and "have not" countries - are arbitrary, not based on any individual's hard work, talents, or even skills, but on where the person happened to be born. And yet there is remarkably little moral outrage surrounding this issue.

One reason for this lack of moral indignation is the widely held idea that labor mobility would be detrimental to the poor in the industrialized world. And indeed, this concept is not entirely unfounded. The fact that wages for unskilled labor will fall as more unskilled labor enters a country seems a reasonably straightforward application of supply and demand.

If this argument were fully true, however, imports from countries with low wages that embody an equivalent (relative) amount of unskilled labor should have exactly the same impact on wages. But, when applied to trade, economists will agree that a potential decline in wages is not a reason to limit imports. It is therefore unclear why this same argument does not apply to actual mobility of labor. Uncomfortably for 'free traders', there may be as much an argument for social equity to oppose imports of labor intensive goods as there is to oppose migration.

Moreover, the poor in richer industrialized countries are immensely better off than the poor (or even the middle income) in poor countries. So from a world welfare point of view the distributional effects of labor movements are (generally) hugely positive.

Given the obviously huge and growing gaps in standards of living worldwide, many people in the developed world doubtless feel the occasional twinge of unease. Yet most continue to cling to the myth that increased labor mobility is unnecessary to raise standards of living.

If one believes the "natural" state of affairs is that income levels will converge without labor mobility then it is easier to rationalize restrictions. Many people hold that trade in goods can provide a substitute for the movement of factors (including people) and that trade barriers can be reduced instead of immigration barriers, to yield the same results. However, there is no evidence that trade is in fact an effective substitute for labor flows.

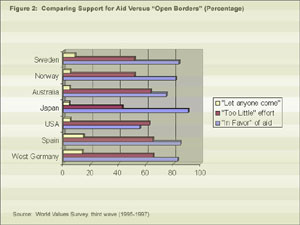

Likewise, many people tell themselves that foreign aid can serve as a substitute for increased migration (see Figure 2). But again, the efficacy of anything like the current levels and structure of aid in promoting substantially faster income growth - at the rates needed to reduce wage gaps - is highly questionable.

However, the views of those in the developed world on migration are also greatly influenced by proximity as the sole determinant of common moral "socia" obligations. People in most industrialized countries think that tolerating excessive differential treatment of people within their national boundaries is "immoral" but have few qualms about the suffering of those living outside their boundaries.

People in Haiti, for example, cause little direct concern to Americans, although they are experiencing great levels of deprivation. If a Haitian manages to reach the United States, however, his very physical presence on US territory creates an enormous set of obligations and political concern. So, one way to think of border controls is a dynamic pre-commitment to not creating an ethical obligation through proximity. Although democratic countries will not allow people to become "second class" citizens while close in proximity, they can tolerate people being treated as worse than 'fourth class' citizens abroad. It is not clear, however, why the common view of "no rights if 'there', but full rights if 'here', and no right to move from 'there' to 'here'," is morally and politically persuasive.

This general denial of people in the industrialized world regarding the increasing pressures for labor flow makes migration a difficult issue to bring to the international and development agenda. The structure of the international system provides for organizations to promote the stability of the payment of international loans (through the International Monetary Fund) and the freer mobility of goods (through the World Trade Organization). Yet migration has remained strictly off the agenda.

The question is, when and how will it come on the agenda? Fortunately, the development "community" has put itself on a clock. The "Millenium Development Goals" (MDGs) aim to halve poverty, ensure universal completion of primary schooling, and reduce infant mortality by two-thirds - all before 2015.

It is obvious, however, that the MDGs are not going to be achieved in every country. So what is the backup plan?

Plan B should be to create mechanisms for enhanced labor mobility to create an integrated, truly global international system. Since no one would embrace entirely free labor flows, the scheme could allocate specific numbers of workers to work in specific industries on an explicitly temporary basis. It could also provide compensation to the sending country for tax loss and "development impact." The country could be allocated a quota for the stock of immigrants, and any failure of return would be deducted from the allowed flow.

The WTO could play an integral role in creating a multilateral agreement to oversee these changes. The organization could be responsible for increasing unskilled migration, separating labor flows from development issues, and linking "immigrant rights" with labor mobility.

No one should underestimate the challenges of bringing greater population mobility - both migration and temporary labor flows - onto the international and national political agendas. The dangers of migration for the recipient countries - of increased inequality, of social stratification, of intolerable abuses of the human rights of the workers - are very real. It is also a difficult challenge to design policies that are simultaneously development-friendly, respectful of human rights, and politically viable in recipient countries. But I am optimistic that if the same degree of intellectual creativity is channeled into that challenge as has gone into making trade freer and increasing capital flows, the world could be just as successful in putting a personal face on globalization.

Lant Pritchett is Lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. This article is adapted from a paper he presented at “The Future of Globalization: Explorations in Light of the Recent Turbulence,” a conference hosted by the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization on October 10, 2003. The complete paper will be presented as a chapter in a forthcoming edited volume of the conference proceedings.