Law’s Special Place in Area Studies

Law’s Special Place in Area Studies

NEW HAVEN: In many US universities, interest in Brazilian politics and institutions has grown considerably. US-based scholars play an ever-more significant role in producing new accounts of Brazilian power structures and dynamics. This state of affairs may create a fertile ground for Brazilian studies, but for those familiar with the “law and development” tradition it also raises concerns. “Law and development” is a product of both intellectual and political conditions that marked the 1960s. Concerns notwithstanding , internationationalization of Brazilian studies, with critical review and questions, is welcomed to counter the current unhealthy trends.

Intellectually, the study of law in the United States had been reinvigorated by “legal realism” and an interest in “law in action” – the production, implementation and effects of legal rules – more than “law on the books,” or the statutes and cases. This shift created opportunities for new academic identities and projects to emerge. The Law and Society Association, a multidisciplinary academic forum dedicated to studies of the law in its social context, was both a product and visible expression of these changes.

Throughout the 1960s, the Cold War divided the world politically. US foreign policy relied heavily on “developmental assistance” to bar what North Americans feared could be the advancement of real socialism. These “development projects” were generally inspired by modernization theory and an understanding that societies tended to “evolve” from “underdevelopment” to “developed” – from commodities-based, rural, autocratic societies to industrialized, urban democracies. The theory also suggested that “underdeveloped” countries could accelerate this “evolutionary” process by adopting structures typical of their “developed” counterparts.

Law was one such structure, with a group of entrepreneurial “legal developers.” These so-called legal developers shared a clear-cut view about law and its relationship to economic and political transformations in what was then called the “Third World.” They thought of law as a system of general rules, backed up by the state and applied by specialized agencies such as courts. They also maintained that law had a “purpose,” that instead of representing transcendental ideals of justice, general legal rules were meant to preserve or change society in a given, purposeful way. It followed that passing and applying proper laws was a powerful way for countries to transition from “underdevelopment” to “development.”

The legal developers considered that “proper laws” were those that would structure and protect a private sphere including property rights, corporate law and capital markets law. Once in place, these laws would produce a US-style marketplace and expand individual freedoms.

Developers offered an agenda including both research and reform. They reviewed laws, legal institutions and legal practices, searching for discrepancies between those in place and the ideal models they had brought to bear. In light of their findings, they didn’t hesitate to propose changes. In Brazil, the developers focused on legal education. Struck by the formalism of Brazilian legal culture, in part an extension of Portugal’s legal traditions, the developers supported reforms to provide Brazilian law students with better analytical skills and more “purposeful” legal reasoning.

As time went by, however, the developers became troubled. To begin with, they encountered socioeconomic structures that didn’t fit their models. Brazil was and continues to be an economy in which the state, before the marketplace, plays a central role in economic development. New laws to structure and protect a private sphere were insufficient for changing this state-of-affairs and, of course, did little to curb Brazil’s authoritarian turn in the mid-1960s.

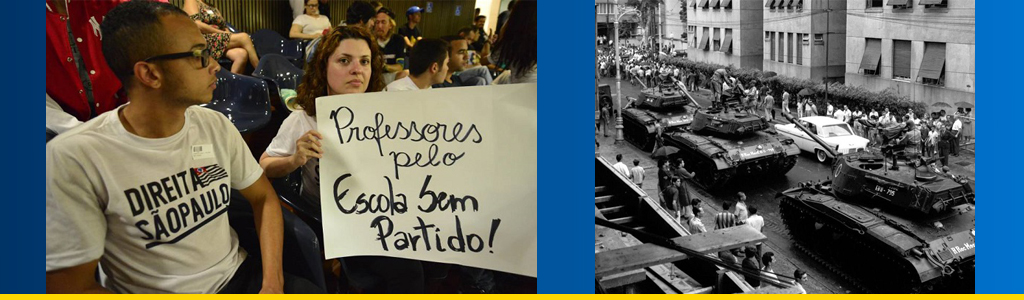

Also, some reforms generated unintended results. As authoritarianism mounted in the wake of the 1964 civil-military coup, the attempt to give lawyers more “purposeful” thinking enabled those working for the state to effectively implement rather than challenge the growing body of illiberal rules. Before long, the developers ended up losing their faith in their own models. Against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and other military interventions, they questioned policy motives behind the push for law and development projects and and whether the United States offered a desirable template for other countries to follow.

.png)

By the mid-1970s, such disappointments, as well as new US foreign-policy priorities, ended the first generation of law and development. Still, its critical legacy endures and, when faced with questions about how the view from the US academy can contribute to research on Brazilian politics and institutions in both countries, those familiar with the “law and development” tradition tend to respond, “It depends.”

Is that view aware of the structural contradictions and conflicts that constitute Brazil and how scholarly work fits such context – whether to challenge or reinforce it? Does the view involve an open commitment to freedom, equality and democracy, instead of the abstract belief that, with the right economic reforms, those will, one day, inevitably come? Is the view based on horizontal and solidary relationships with Brazilians, beyond elites who often make strategic use of foreign connections to enhance their own power?

To develop a better “view” and avoid “self-estrangement” requires a response from a collective and institutional level. University programs must provide an infrastructure allowing students and faculty to learn the language, immerse themselves in the Brazilian context and culture, and develop relationships that challenge certainties and assumptions.

Needless to say, none of this is easy. Obstacles begin in the United States, where financial support associated with foreign-policy interests has long gone away and the reigning academic structure offers no tangible rewards for the time and energy spent by faculty in efforts to create Brazil studies programs.

Hardships have also grown in Brazil, where despite pressures for “internationalization,” higher education institutions face cutbacks in funds and threats of privatization. Affirmative action and policies that have made student bodies more inclusive and diverse are under siege, and anti-intellectualism and attacks on academic freedom have mounted, as represented by the Escola Sem Partido movement and the recent election of Jair Bolsonaro.

With persistence and mutual support, however, these are challenges that can be overcome. And while for some of us a call to chart “the road ahead” for Brazilian studies in the United States may raise questions and doubts, hopefully it will also evoke more inspiring images, like that in the 1856 poem of Walt Whitman, wherein “road” appears as a metaphor for a utopian, “open” space, finally attained:

Allons! the road is before us!

It is safe – I have tried it – my own feet have tried it well – be not detain’d!

Fabio de Sa e Silva is assistant professor of International Studies and Wick Cary Professor of Brazilian Studies, University of Oklahoma and co-director of the Brazil Studies Program. This article is based on his paper delivered at the conference “Brazilian Studies in the United States: The Road Ahead,” held November 30 and December 1 at Yale University’s MacMillan Center. E-mail: fabio.desaesilva@ou.edu