Oman Strives for Neutrality in the Middle East

Oman Strives for Neutrality in the Middle East

UPDATE: Sultan Qaboos bin Said, age 79, has died. His cousin Haitham bin Tariq al-Said has been sworn in as the next sultan of Oman.

RABAT: Like many of the lesser-known countries in the Global South, Oman rarely commands the attention of the international community. For the opaque politics of this Arab sultanate, though, the obscurity appears intentional. Omani officials have relied on their country’s relative anonymity to exercise considerable influence behind the scenes, maintaining contacts with competing regional powers such as Iran, Israel and Saudi Arabia in addition to the world powers battling for control of the Middle East, among them China, Russia and the United States. As tensions between Iran and the United States rise over the American-orchestrated death of the Iranian spymaster Qasem Soleimani, Oman's longtime role as a regional mediator may become more important than ever.

Iran wages a cold war against the Western world while Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates prosecute an all but endless war in Yemen. Oman shares land borders and maritime boundaries with Iran, the UAE and Saudi Arabia and has managed to distinguish itself as an island of stability in the region. In fact, the sultanate’s oft-cited reputation as “the Switzerland of the Middle East” has allowed Omani officials to serve as mediators in these conflicts.

Former US President Barack Obama often references the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – the international agreement limiting the Iranian nuclear program – as among his major accomplishments. But he might not have realized this achievement without Omani assistance. Oman, a close ally of the United States in the Middle East and perhaps Iran’s only reliable partner in the Persian Gulf, facilitated a backchannel between the US and Iranian diplomats that laid the groundwork for the talks that ended with the JCPOA in 2015.

In the case of Yemen, Oman has hosted peace talks between the Emirati- and Saudi-led coalition backing a frail Yemeni government and the motley alliance’s tenacious opponents, the Houthis, a collective of rebels backed by Iran. Whereas most other member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council joined the Emirati and Saudi war effort at one point or another, Oman’s respected history of neutrality in Yemen and the region as a whole underpins its role as an intermediary.

After the United States targeted Soleimani's vehicle in Baghdad, Oman immediately urged Iran and the United States to pursue dialogue to deescalate tensions.

In many ways, neutrality and obscurity go hand in hand in this country of 4.9 million people. The sultanate has more or less refrained from taking sides in the ever-expanding roster of Middle Eastern conflicts since Omani Sultan Qaboos bin Said al-Said ascended the throne in 1970. Therefore, Oman has had little reason to engage in the kind of headline-grabbing interventions that have often characterized American, Emirati, Iranian and Saudi foreign policy. In turn, the few outsiders who do think about Oman know it as a neutral country and a tourist destination, not as a source of conflict.

As Middle Eastern and Western pundits alike have lambasted regional and world powers for their part in proxy wars on the Arabian Peninsula, in the Levant and in the Maghreb, Omani officials have earned goodwill by bankrolling cultural diplomacy and sustainable development. Oman invites Western students to the country to study Arabic and sponsors a prize for environmental scientists in cooperation with the United Nations.

In addition to Qaboos’ recent contributions to Omani foreign policy, the sultanate has adopted an isolationist, noninterventionist approach to the world because of its demographic and historical characteristics. Unlike their Shia and Sunni neighbors, most Omanis practice Ibadism, a conservative, secretive offshoot of Islam that emphasizes moderation and tolerance. In keeping with their traditions, Ibadism’s adherents tend to keep to themselves. The downfall of the Omani Empire, which once extended from Balochistan to Zanzibar, also taught Omani leaders the dangers of the expansionist ambitions that tempt their Iranian and Saudi counterparts.

Oman’s lack of interest in pursuing the rivalries that have riven the Gulf as well as the rest of the Middle East explains the depth of its friendships across the region and the world in general. The sultanate has hosted delegations from Israel and Saudi Arabia, cut trade pacts with China, Iran and Russia, and received military aid from Britain and the United States. Few other small powers could balance relationships with so many competitors at once.

Beyond growing Oman’s list of allies and keeping the sultanate out of the spotlight, the country’s foreign policy has shielded its internal affairs from outside scrutiny. Like its neighbors, Oman has limited human rights and freedom of expression in particular – even imprisoning critics occasionally – yet Omani officials have encountered much less criticism than their Emirati and Saudi counterparts. The country’s status as an absolute monarchy has also received little attention, and many Omani officials engage in torture without fear of consequences.

Despite the many ways in which Oman has gained from its foreign policy, contemporary history signals that this Omani renaissance may be coming to an end. Oman’s most powerful neighbors, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have proved frustrated with the sultanate’s opaque decision-making. In 2011 and again in 2019, Oman claimed to have discovered Emirati spy rings operating on its territory. Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, has pressured Oman to move away from Iran. The kingdom’s leadership has long wanted Oman to halt trade with Iran, and some analysts have speculated that Saudi Arabia could withdraw its investments from the sultanate to compel Omani compliance.

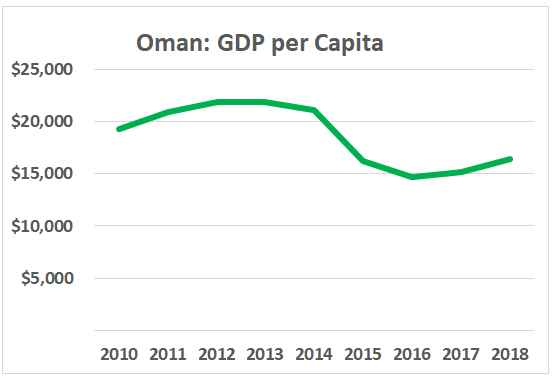

.jpg) (Source: World Bank and Observatory of Economic Complexity)

(Source: World Bank and Observatory of Economic Complexity)

Two longer-term challenges indicate that Oman may struggle to afford the luxury of neutrality in the coming years. Many analysts question what will happen to the sultanate’s foreign policy once Qaboos, a 78-year-old monarch, dies or relinquishes power. Qaboos has yet to pick a successor. Oman’s dwindling oil reserves, which could be depleted as soon as 2032, have heightened the lack of clarity over the sultanate’s future. Observers expected revenues from fossil fuels to fund more than 70 percent of the 2019 budget, predicated on a price of $58 per barrel. If either problem leads to a constitutional crisis, this little-known neutral country may find that, in fact, it has few permanent allies.

In the face of these looming challenges, Oman can try to capitalize on its immediate relevance to geopolitics by building on its diplomatic and economic partnerships to cement permanent alliances. Neither the principals of the American-Iranian contest for dominance of the Middle East nor the combatants in the Yemeni Civil War have access to a better intermediary than Oman. Omani officials could leverage their diplomatic skill in courting financial assistance or trade guarantees from other powers in need of such intercession. Iran, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the US may also need the sultanate’s assistance to determine the future of the Strait of Hormuz as tensions remain heated. Oman still has the diplomatic capital to extract these actors from the region’s persistent conflicts.

Whether Oman can sustain a foreign policy built on neutrality and obscurity well into the future remains a question for the few analysts who reflect on the sultanate’s trajectory. So far, Oman has fared better than the Gulf’s regional powers, from Iran and Qatar to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, in dodging ceaseless conflicts that have entangled so many other Middle Eastern players.

The North African and Western Asian countries that have made a point of distancing themselves from the region’s conflicts, such as Kuwait and Morocco, tend to succeed where so many others have failed. By ignoring the temptation to pursue regional hegemony, these likeminded monarchies have escaped the fate of Iran, Saudi Arabia and other oft-criticized middle powers viewed as pariah states by many in the international community. For its part, Oman has continued to offer the best example of a neutral country in a region bereft of them.

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture and politics in Africa and Asia. His research has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.