Questions on Succession in North Korea

Questions on Succession in North Korea

HONG KONG: The reappearance of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un at a factory opening on May 10 silenced rumors that he had died or was incapacitated. After 21 days out of public view, Kim appeared confident, smiling and smoking as he cut the ribbon accompanied by his sister Kim Yo Jong and other officials.

Analysts and journalists who leapt onto the “Kim is dead” bandwagon were left looking silly. But Kim is obese and a chain-smoker, reportedly a heavy drinker, and appears to walk with a limp. Moreover, since May 10, he has only made a handful of public appearances – far fewer than during the corresponding period last year. Although only 36, he could be a candidate for a health event. Since he has no obvious heir, this prospect raises a host of questions.

When Kim’s grandfather Kim Il Sung died suddenly in July 1994, at age 82, he had just welcomed former US President Jimmy Carter to Pyongyang and agreed to negotiations with Washington on the North’s nuclear weapons program. His successor Kim Jong Il followed the same path, eventually agreeing to freeze the program in return for American aid and improved diplomatic relations.

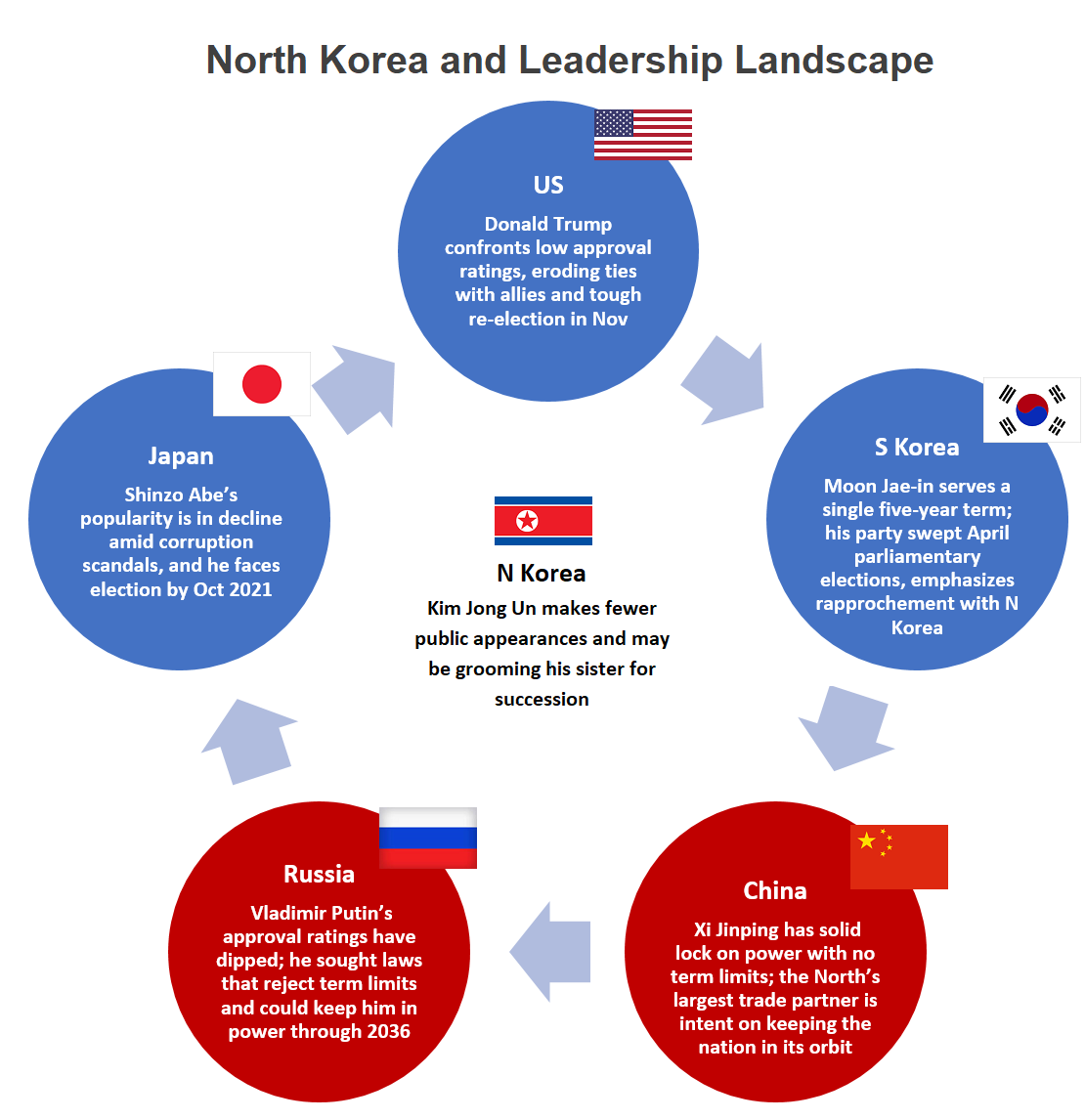

Should Kim Jong Un leave the scene, however, the international environment is dramatically more polarized, with rising tensions between the United States and China as well as US allies. Frustrated with his failure to convince Washington and Seoul to ease international sanctions, Kim outlined a major strategic reorientation last December that ruled out dialogue with the United States or South Korea and focused instead on ramping up military power. This hardline approach could lead to tests of medium-range Rodong and short-range Scud missiles, submarine-launched missiles or other weapons that approach – but do not cross – Washington’s ban on North Korean tests of nuclear devices or intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Pyongyang has refrained from such moves since it began talking with the Trump administration in 2018, while continuing to produce weapons-grade plutonium and uranium and improving its missile technology. However, with North Korean military prowess growing, and President Donald Trump preoccupied with Covid-19 and a stiff reelection fight, Kim may think there is little the United States would or could do to retaliate if he did stage a nuclear or ICBM test. Moreover, if it appears that Joe Biden is indeed likely to defeat Trump, Pyongyang may, as one former US diplomat put it, “want to lay down a marker in advance of the election.”

This is the dangerous context in which North Korea’s internal succession and external maneuvering would play out if Kim should die. His country has proved surprisingly resilient, surviving two leadership successions, severe famine and international sanctions.

Only those with a direct blood link to Kim Il Sung are thought to have the legitimacy to lead. Analysts believe Kim Jong Un has three children. All are young, the oldest about 10 years of age. His older brother, Kim Jong Chol, was passed over by Kim Jong Il, apparently for lacking the toughness to rule. There has been much speculation about his sister, widely seen as her brother’s trusted confidante.

While previously behaving more like a valet than a potential successor, in recent weeks, she has taken on an increasingly public role. In June, she issued a series of denunciations and threats targeting South Korea, with her statements featured prominently in North Korea’s official media. Although it is hard to imagine a young woman acquiring the authority and legitimacy to rule in North Korea’s conservative, male-dominated society, even with her bloodline, her growing influence fuels speculation she is being groomed to succeed her brother.

If Kim Jong Un were to die sooner rather than later, North Korea – and its nuclear weapons, missiles and 1.2 million-strong army – would enter uncharted waters. Even a relatively orderly succession would likely see a significant increase in the role of the stridently anti-American armed forces. A struggle for power could conceivably lead to civil unrest, an outflow of refugees into China and South Korea, and in the worst case, armed clashes among competing factions and loose nuclear weapons.

In this kind of situation, the priorities of Washington, Beijing and Seoul would diverge – the United States seeking to secure the North’s nuclear arsenal; China to maintain the North as a pliant buffer state; and South Korea, committed to engagement and hoping for reunification, eager for stabilization. Yet officials in the three capitals are not having the critical conversations required to ensure that a bad situation would not become even worse.

The United States and South Korea have long had contingency plans for a crisis, addressing everything from defending the border to seizing Pyongyang's nuclear arsenal. But the US-South Korea alliance is crumbling, with Washington and Seoul at loggerheads over how much Seoul should pay for hosting US forces. Trump’s threats to scale down the US military presence have made coordinating a response to disruptions in North Korea more problematic.

Beijing, which probably knows more about the North’s internal dynamics than Washington or Seoul, is widely believed to have plans to deploy military forces to ensure North Korea’s survival as a viable buffer state. China has long resisted US requests to discuss contingency planning – even while facing the likelihood of US or South Korean military intervention to seize the North’s nuclear weapons – in part to avoid revealing its hand and in part to avoid upsetting Pyongyang. With Sino-American relations in a downward spiral, Beijing has even less incentive to cooperate.

In 1950, the prospect of American and South Korean troops operating along its border with the North led China to enter the Korean War. Despite the world’s preoccupation with COVID-19, the key parties need to start talking as North Korea faces an uncertain and dangerous future.

One way to do this might be to hold a series of so-called Track 1.5 or Track 2 diplomacy – unofficial interactions between government officials, often facilitated by a third party like a think tank, or informal conversations among former senior officials, experts and scholars. Such gatherings could include the United States, China, South Korea and possibly Japan.

This approach has been tried over the years in relation to North Korea, and, as former State Department Korea expert Evans Revere, who participated in such gatherings, has noted, “it might help open some doors.”

But in the current poisonous climate, even attempting to arrange such meetings could be problematic. The absence of adequate coordination or discussion of contingency plans between Washington, Beijing and Seoul, however, leaves the world ill equipped to handle what could be an extraordinarily dangerous crisis.

Mike Chinoy is a non-resident senior fellow at the University of Southern California’s US-China Institute. He has visited North Korea 17 times and is the author of two books about the country: Meltdown: The Inside Story of the North Korean Nuclear Crisis and The Last POW. His latest book is Are You With Me? Kevin Boyle and the Rise of the Human Rights Movement.