To Resolve the Syrian Crisis, Partition Is Necessary

To Resolve the Syrian Crisis, Partition Is Necessary

BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA: Syria was never a country whose 14 provinces and 8 main communities were voluntarily bonded together by secularism and tolerance. Not surprisingly the six-year civil war became violently sectarian and ethnic. At ceasefire talks on May 4 in Astana, Kazakhstan, Russia proposed four “de-escalation zones” with Iran, Turkey, and itself serving as guarantors. Yes, partition is necessary. But having three nations that greatly abet the strife serve as enforcers will not produce peace. An impartial plan must be formulated and implemented.

Since 1971, under father Hafez al-Assad and son Basher, Syria has been ruled by Alawites comprising 13 percent of the population. Through oppressive rule, they and their Shiite partners engendered among Sunnis, 74 percent of the population, a desire to extract retribution. Christians, Druze, Jews and Yezidis found a degree of security by bending to the Alawite leadership’s wishes, but thereby came to be seen as complicit. After the civil war broke out in March 2011, the Syrian president’s security agents increased imprisonment, torture and execution of dissidents. His air force launched barrel and hose bombs and chemical attacks on civilians.

Bashar al-Assad’s international partners became entwined in this ethno-sectarianism. Russia deploys its aerial firepower to reinforce the Alawites’, most notoriously by bombing hospitals in Sunni areas. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards and proxies including Iraqi Shiite militias and Lebanese Hezbollah purge captured towns of Sunni Arabs and Kurds. The regime’s foes fight back in religious and ethnic factions, too. The self-proclaimed Islamic State and Al-Qaeda affiliates are backed by Sunni financiers and fighters from the Persian Gulf states and the Caucasus. The Free Syrian Army counts on financing and weapons sourced from Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Syrian Kurds, reliant on US and EU resources, work to carve out their country.

Russia’s goals in entering the Syrian arena include quashing the Sunni militancy to sever its links to Chechnya and threats to Russian society, maintaining Syria as a political client state, and expanding its Middle East and Mediterranean presence through Syrian bases. Iran’s goals are similar to those of Russia in ending Sunni militancy in Syria and severing those terrorists’ links to Iraq and threat to Iran, maintaining Syria as an Alawite-controlled religious surrogate for influence westward across the Middle East and Mediterranean, plus stymieing Saudi Arabia’s growing influence. Turkey’s direct involvement focuses on suppressing Kurds, who are regarded by Ankara as worse than Islamist terrorists due to their nationalist aspirations, and curbing their control over strategic Syrian territory. Saudi Arabia’s actions in the civil war are largely aimed at boosting Riyadh’s influence in the Middle East as the head of Sunni nations, smothering Shiite political aspirations across the Middle East and ending Iran’s reemergence as a regional power. Israel takes action in Syria to thwart military attacks from Assad’s regime, Sunni terrorism from the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda cronies and Iran from re-arming its proxy Hezbollah.

Russia’s goals in entering the Syrian arena include quashing the Sunni militancy to sever its links to Chechnya and threats to Russian society, maintaining Syria as a political client state, and expanding its Middle East and Mediterranean presence through Syrian bases. Iran’s goals are similar to those of Russia in ending Sunni militancy in Syria and severing those terrorists’ links to Iraq and threat to Iran, maintaining Syria as an Alawite-controlled religious surrogate for influence westward across the Middle East and Mediterranean, plus stymieing Saudi Arabia’s growing influence. Turkey’s direct involvement focuses on suppressing Kurds, who are regarded by Ankara as worse than Islamist terrorists due to their nationalist aspirations, and curbing their control over strategic Syrian territory. Saudi Arabia’s actions in the civil war are largely aimed at boosting Riyadh’s influence in the Middle East as the head of Sunni nations, smothering Shiite political aspirations across the Middle East and ending Iran’s reemergence as a regional power. Israel takes action in Syria to thwart military attacks from Assad’s regime, Sunni terrorism from the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda cronies and Iran from re-arming its proxy Hezbollah.

Within the current battlefield, the United States and its EU partners have been more distant players, supplying funds and armaments to anti-Assad rebels while occasionally bombing Syrian government and Islamist terrorist bases. Washington and its European partners see only limited gains – transient victory over Sunni terrorism within a single country, hope of preventing instability spreading to neighboring nations and reduction of refugee flows to the West.

Syria already has been de facto partitioned by the opposing forces of the civil war. No political leadership represents the many domestic factions, and none could control the territory militarily and politically, or run a national administration. Moreover, there is no currently-envisaged governing coalition that would be acceptable to the major international players. Consequently for Syria the solution must be multilateral negotiations leading to separation into geographically-discreet, self-governing regions based on communal affiliations. Indeed partition was first attempted under the League of Nations French Mandate of 1923-1946.

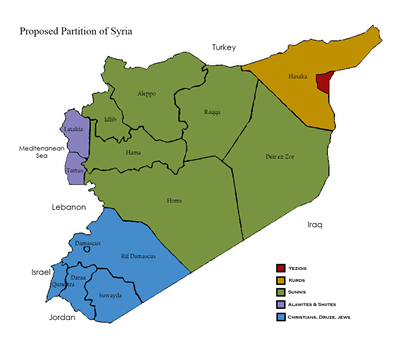

The Sunni Arab majority should hold the central and northern provinces or governorates of Homs (Hims), Hama, Idlib, Aleppo (Halab), Raqqa and Deir ez Zor (Dayr az-Zawr). Kurds could control the northeastern province of Hasaka. Alawites and Shiites could retain the Mediterranean coastal provinces of Latakia and Tartus. Christians, Druze and the few remaining Jews can regain safety and security by sharing the southwestern and southern governorates of Rif Dimashq which surrounds Damascus, Quneitra (Qunaitra), Daraa (Dar‘a) and Suwayda along the borders with Lebanon, Israel and Jordan. Yezidis could gain a small enclave in Hasaka along the Syria-Iraq border. Each community could then rebuild its society and economy.

Population transfers are necessary, such as Kurds from Aleppo to Hasaka and Alawites from Damascus to Tartus, for separation to be achieved. But a bloodbath similar to what accompanied the partition of British India can be prevented if President Vladimir Putin’s proposal that Russian, Iranian and Turkish forces act as enforcers is rejected – because they already have shown themselves to be brutally partisan. Russia’s scheme would even bar the US-led international coalition from safeguarding anti-Assad forces and civilians or Israel from protecting itself within Syria. Coalition aircraft and troops are not permitted into the de-escalation zones, even though Russian forces already there as monitors have not stopped the fighting. Worse, Assad and the Islamists have reached a deal under which those terrorists are being relocated from the regime's areas like Damascus to provinces held by moderate rebels.The US and EU should push for a more viable plan rather than permit Moscow, Tehran and Ankara to stage a covert takeover of Syria which would certainly result in the decimation of Sunni opponents of Assad, Christians, Druz, Jews, Yezidis and Kurds.

Semi-autonomous or fully-autonomous divisions do bring the potential for future problems. Assad and his regime, despite war crimes, may go unpunished. But leadership change in Syria could be part of the deal. When they met on April 12, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov conceded that Russia is not staking everything on Assad, and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson acknowledged that the United States would accept the Syrian dictator’s departure occurring in an orderly way. The Sunni heartland may not completely eliminate radical Islam from its midst. But the United States and the European Union could work with Middle East countries to move swiftly at the first signs of resurgence and prevent Syria from being overrun again by terror groups. Kurds may seek to expand their Syrian autonomous region by supporting secessionist rebels in eastern Turkey, northern Iraq and northwestern Iran. But they could be convinced that so doing would lead to dire retaliation. Druze, Christians and Jews would still face discrimination, but could reach security, economic and cultural agreements with Israel and the West to reduce need for interaction with former oppressors.

Major and regional powers will not stop trying to influence the ethno-sectarian regions. Russia and Iran may retain naval and air bases among the Alawites, but their overland and overflight access can be blocked by the Sunni and Kurdish regions. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Emirates could shape the societies of Sunni Syria. Turkey and the Kurds are unlikely to end their cross-border altercations. But such challenges would be continuation of ones currently in place, yet on a lesser scale because no foreign nation will have sway over the entirety of the Syrian landscape. Moreover Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey could be warned that using their Syrian spheres of influence to stir trouble in the region, generally or harm Israel specifically, would be firmly met by economic, political and military responses from the United States and the European Union.

Partition may not the ideal outcome for Syria’s crisis, but is necessary and can be done correctly.

Carol E. B. Choksy is Lecturer in Strategic Intelligence in the School of Informatics and Computing at Indiana University and CEO of IRAD Strategic Consulting, Inc.

Jamsheed K. Choksy is Distinguished Professor of Central Eurasian Studies and Professor of Iranian Studies in the School of Global and International Studies at Indiana University. He also serves on the US National Council on the Humanities at the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Comments

Sometimes an article is written that is SO silly it defies comment. This is one such article.

The article offers a suggestion and suggestions are urgently needed.

"An impartial plan must be agreed upon and enforced by nations who did not contribute to the strife."

No, it must be agreed upon by the Syrian people. SELF DETERMINATION is key.

If only there was a historical record to show why the idea of creating 3 land-locked countries is a bad idea... Oh wait, there is.

Not to mention, after the Yazidis and Kurds are eliminated by the Turks and the Islamists from northern Iraq, how long before the newly emboldened leaders of the proposed 100% Sunni Muslim nation of "Most of Old Syria" decide to regain their territory from the "heritics" in coastal "Alawi-land" and "The Leftover People's Almost-Lebanon?" This is not a real-world answer.