Retirement: No More Golden Years

Retirement: No More Golden Years

NEW YORK: A right to work counts among basic human rights, but retirement goes unmentioned. Nevertheless, government-sponsored pensionable retirement has evolved into a popular social institution worldwide, especially in industrialized countries. Statutory retirement ages are in flux around the globe and public protests in Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, Croatia, Iran, Belgium and elsewhere attest to the centrality of retirement programs to societal wellbeing and poverty reduction among the elderly.

Governments introduced pension programs for workers near the start of the 20th century. Until then workers toiled until death or disability, and this remains largely the case for workers in less developed countries. Statutory retirement ages of the earliest national programs were typically greater than life expectancy at birth. In the United States, for example, when the 1935 Social Security Act was adopted, the official retirement age was 65 years while life expectancy for American males was under 60 years.

Today most governments have established pensionable retirement programs or social security providing financial support to many elderly men and women. Many programs are based on the three-legged stool of government benefits, employer-provided pensions and personal savings – all of which face serious challenges.

Retirement programs, similar in purpose, differ considerably in scope, coverage, contributions, requirements, taxes, eligibility and benefits. Official retirement ages, for example, range from 50 to 70 years, with most concentrated between 60 and 65. Although women typically live longer than men, the statutory retirement age for women in Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Chile, China, Iran, Israel, Poland, Russia, Turkey and the United Kingdom is lower than men’s.

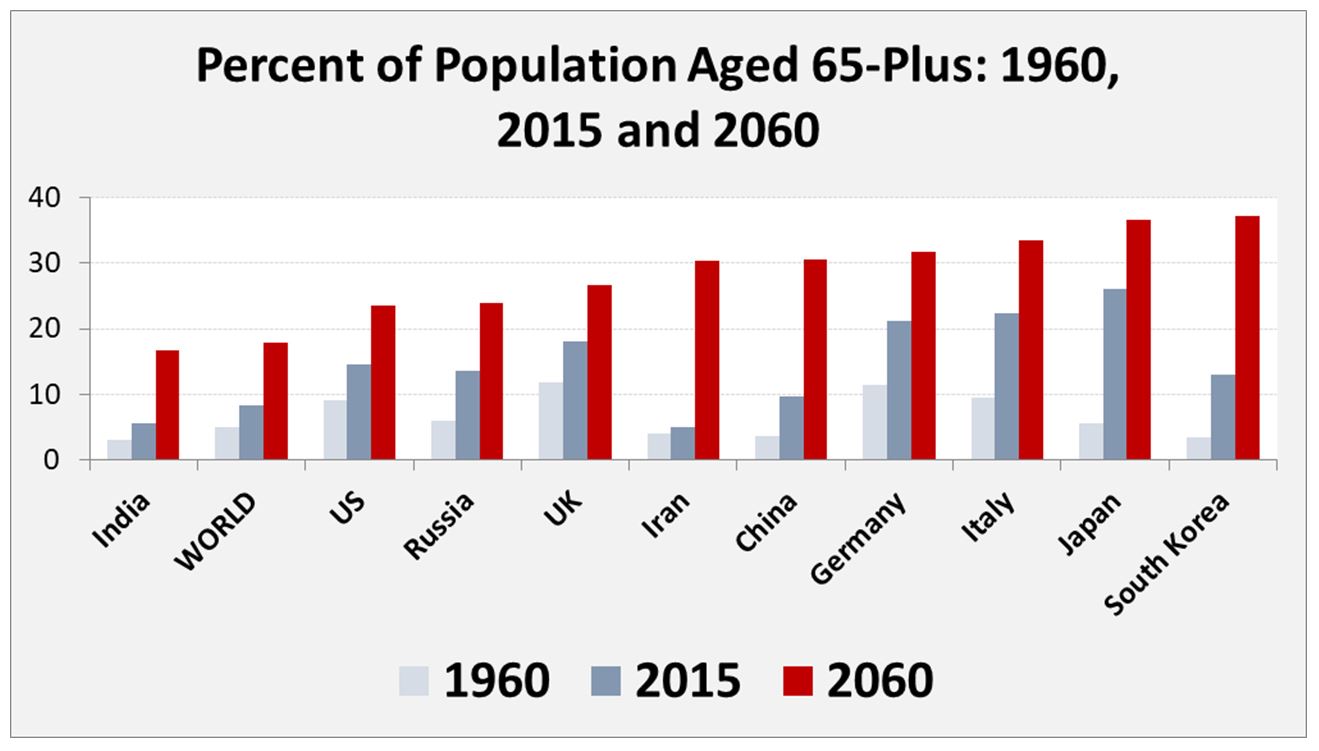

With countries worldwide experiencing population aging, government-sponsored retirement programs incur increased costs in response to growing proportions of retired older persons. In turn, those demographic changes challenge the long-term sustainability of retirement programs. Marked increases in proportion of the population aged 65 years and older are expected to continue, particularly among industrialized countries. Some countries, such as China, Germany, Japan, Iran, Italy and South Korea, are projected to have people aged 65 years and older account for about a third of their populations.

Increased longevity results in more years available for retirement, again translating into increased costs. Since the middle of the 20th century, average life expectancy at age 65 years for the world has increased by more than five years. In some countries, such as Australia, China, France, Italy, Japan and South Korea, the increase in life expectancy at 65 during the past half-century has been more than seven years. A notable exception to this global longevity trend is Russia, where unfavorable health conditions have increased life expectancy at age 65 by only two years.

Many retirement programs are underfunded. In response to the rising costs of aging populations, longer periods of retirement and fewer tax-paying workers per retiree, governments are adopting steps to reduce obligations and improve the financial sustainability of retirement programs. Public opposition greets government plans, including in most high-income OECD countries, to delay retirement by gradually increasing statutory retirement ages.

Some countries, including Denmark, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal, index official retirement ages to life expectancy. Again, widespread resentment greets such proposals as life expectancies vary across occupations, incomes, educational levels and race as well as between men and women.

In the Netherlands, many support early retirement for workers in physically demanding occupations, which tend to have lower life expectancies. In the United Kingdom higher educational attainment translates into longer survival rates for those 65 years and older. Women’s life expectancy at age 65 in Japan continues to be about five years more than men’s. Life expectancy at birth in the United States also varies markedly by sex and income. Life expectancies of American women are approximately five years greater than those of men across major racial groups, with the highest and lowest life expectancies observed among Hispanics and blacks, respectively. Greater differences in life expectancy at birth are observed between rich and poor regions of the United States – from 87 in affluent parts of Colorado to 66 on Native American reservations in South Dakota.

Governments also try reducing pension retirement benefit by switching to less favorable indexation. The United States, for example, changed inflation measures for US social security payments in 2000 to cost-of-living allowances based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, reducing buying power of the monthly benefits.

Governments also increase taxes or redirect taxes from other government programs – the least popular approach. Politicians tend to postpone addressing costly long-term problems, such as retirement obligations, and younger taxpayers are reluctant to pay additional taxes for a far-off retirement that they may never receive. Increasing taxes is difficult to implement in countries where population aging and low birth rates result in fewer tax-paying workers per retiree. In South Korea, for example, the number of workers per retiree has fallen from 10 in 2000 to about five today and is projected to decline to two by 2035.

Private-sector retirement plans have also changed markedly, in turn influencing public-sector practices. Traditional defined benefit pension plans have declined in many countries. In the United States, for example, the proportion of private-sector workers with a defined-benefit pension declined from close to 90 percent in 1975 to around 30 percent today. Surveys of multinational corporations report that defined-benefit pensions are considered outdated. Less costly, less risky defined-contribution pension arrangements are the preferred alternative for companies and even workers.

Long lifespans, insufficient personal savings and risky old-age pensions require many elderly to work past the age they had expected to retire. In Japan, New Zealand and South Korea, for example, a third or more of the men aged 65 years and older remain in the labor force.

In sum, inescapable demographic trends and financial realities coupled with the troubling state of government affairs pose significant consequences for retirement programs:

Higher retirement age: With the goal of reining in rising costs, official retirement ages, including early retirement ages, are gradually being raised. Many governments want men and women to delay retirement until their late 60s or older.

More taxes for retirement pensions: With population aging, increased longevity and fewer workers per retiree, many governments must increase taxes or redirect tax monies from other programs to pay for rising retirement costs.

Transition to defined-contribution pensions: Private- and public-sector employers are moving from traditional defined-benefit pension arrangements to defined-contribution pension plans, thereby shifting financial risks from employers to workers.

Insufficient savings: Despite repeated warnings, most older workers have not saved enough for retirement. The challenge grows with increasing longevity. In addition, most workers lack the financial skills to make informed decisions about investing limited savings for sustainable retirement income.

Reduced retirement benefits: Benefits are likely to be reduced by adjusting inflation indexes, income thresholds, work requirements, means testing, surtaxes or eligibility.

Working longer: Working longer is the likely future for many men and women, especially those with limited savings. Many workers will find themselves working well past the age they had expected to retire, some to stave off poverty.

More changes are anticipated for retirement programs, and nearly half of today’s workers and retirees worldwide expect future retirees to be worse off than those currently retired with some concluding they cannot afford to retire. Ongoing trends justify these disquieting assessments.

Joseph Chamie an independent consulting demographer and a former Director of the United Nations Population Division.

This article was published November 13, 2018.

.JPG)

.JPG)

Comments

Given the difficulty of raising taxes and the unfairness of raising retirement ages for many workers, one possible partial solution is capping the current real value of maximum social security monthly payments. They would still be indexed to inflation, but the workers earning the maximum would know they would not receive more than current high-income retirees do. As wages slowly rise in real terms, more workers would bump into the maximum, but it would be gradual and only a modest cut from what is now promised. Typically, recipients getting the maximum have also saved in retirement accounts and rely on social security for only a fraction of their total income. The vast majority of workers would not be affected. This would help but not completely solve the problem of long term insolvency.