Sex, Gender and Identity Revolution

Sex, Gender and Identity Revolution

.jpg)

NEW YORK: With its antecedents brewing for decades, the 21st century has ushered in a sexual, gender and identity revolution. Increasingly, members of the LGBTQ community – lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning – are becoming more visible and outspoken, consequently gaining recognition and acceptance. At least 26 nations now allow marriage equality and 27 others allow civil unions and partnerships.

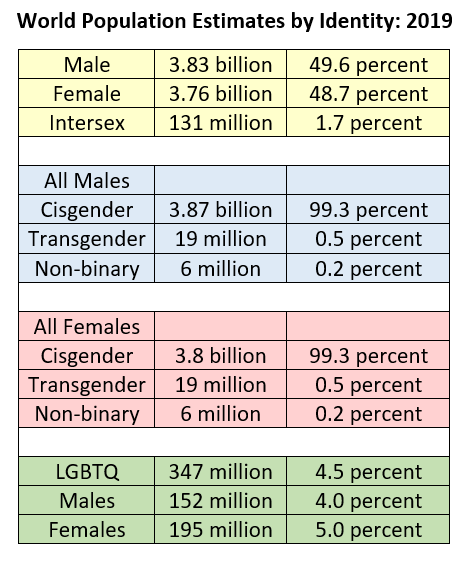

Traditionally, societies divided human populations into two sex categories: male and female, based on reproductive systems. However, some 131 million people, or 1.7 percent of the world’s population, fall outside of those two categories based on having intersex conditions.

Ambiguous genitalia can be attributed to an array of health issues related to hormones, chromosomes, gene mutations and more. Still, about 70 nations criminalize homosexuality, most in Africa and South Asia, with the death penalty possible in Iran, Mauritania, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, the Sudan and Yemen. Brunei announced strict interpretation of Sharia law in April, including death by stoning for homosexuality and adultery, but has since said that the rules won’t be enforced.

People with intersex conditions are those whose anatomy or genes do not fit typical biological definitions of male or female. For example, an individual might be born appearing to be female with mostly male-typical anatomy on the inside. Gender, in contrast to one’s biological sex, can refer to social roles based on a person’s sex or personal identification of one’s own gender, masculine or feminine, based on internal awareness or gender identity. With many terms and definitions used for gender identity, sensitivity and uncertainty may arise regarding the appropriate terminology.

Society is adjusting to a multitude of categories. Facebook offered users more than 50 gender options in 2014 and allows custom pronouns. The dating app Tinder allowed potential daters to choose among at least 37 options. The Common Application, used by more than 600 US colleges, also provides applicants with a free-response box to elaborate on how they self-identify.

Nevertheless, there is entrenched opposition to gender identity being culturally defined or individually determined. In the United States, for example, the federal government is trying to define gender as a biological, immutable condition determined by genitalia at birth. Such a definition would adversely affect an estimated 1.4 million Americans who identify as a gender other than the one assigned at birth:

The term cisgender describes people, estimated at about 99 percent of the population, whose assigned sex and gender identity are much the same or in line with each other. A cisgender person, for example, is male with a masculine gender identity or female with a feminine gender identity. Transgender describes people, estimated at about 0.5 percent of men and women, whose gender identity or expression does not match the sex they were assigned at birth. A transgender person, for example, may identify as a woman though born a male or identify as a man though born a female. Not all transgender people identify as male or female with some identifying as more than one gender or no gender at all.

The World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association recently reclassified transgenderism from a psychiatric disorder to a condition related to sexual health. According to WHO, gender incongruence is characterized as a “marked and persistent incongruence between an individual’s experienced gender and the assigned sex.”

Individuals whose gender is not male or female may use a variety of terms to describe themselves, including non-binary, agender, bigender, and genderqueer. While some are non-binary, most transgender persons have a gender identity that is either male or female. Non-binary people, estimated at about 0.2 percent of men and women, are usually not intersex. Generally, they are usually born with bodies that may fit typical definitions of male and female, but their innate gender identity is something other than male or female.

(Sources: Estimates compiled by authors)

Global statistics on the LGBTQ population are limited, largely by the fact that most official government records do not include data on sexual orientation and gender identity. Governments typically collect demographic data, issue identification documents and establish policies, laws and programs that distinguish individuals on the binary basis of sex. Population censuses, civil registration systems, identity cards, voting rolls and birth, marriage and death certificates, for example, differentiate people by and large on the male-female binary classification. Furthermore, due in large part to discrimination and other negative consequences in many parts of the world, members of the LGBTQ community are reluctant to reply accurately to questions about sexual orientation and gender identity. As a result, such questions typically result in high non-response rates.

LGBTQ population estimates are limited and vary depending on a variety of factors, including how questions are phrased – whether based on self-identification, physical attraction or sexual behavior – and how people are interviewed. Consequently, LGBTQ populations are likely to be undercounted.

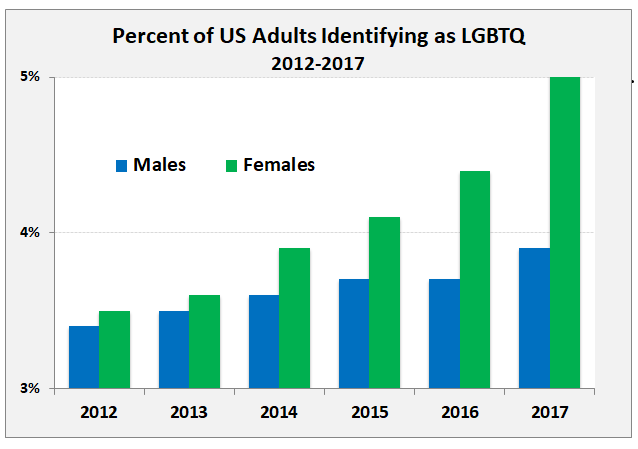

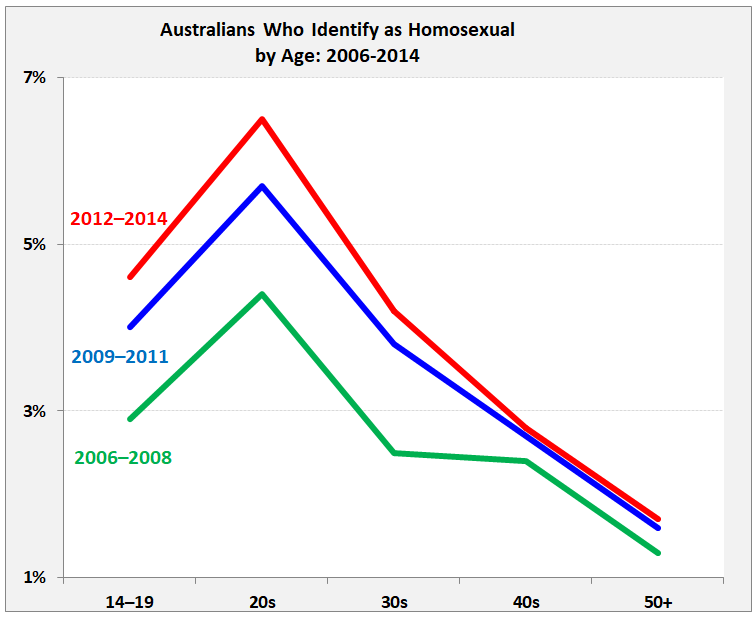

Despite definitional and measurement limitations, disclosure of LGBTQ status in nationally representative surveys has been consistently on the rise from one survey round to the next. That upward trend is likely to continue since disclosure is more frequent among younger cohorts. In addition, the increasing proportions of people identifying as homosexuals, bisexuals or transgender may reflect the general public becoming more accepting.

Based on data from sample surveys in a handful of countries, some insight and tentative estimates may be gained on the levels and trends of sexual orientation and gender identity. In United States, for example, the proportions of adults identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender have been rising in recent years, reaching approximately 4 and 5 percent of males and females in 2017, respectively, or no less than 11 million adults. Also, while females continue to be more likely to identify as LGBT than males, that difference may be due to more social acceptance for women.

Among the 14 OECD countries where survey estimates are available, lesbians, gays and bisexuals account for close to 3 percent of the adult population, or no less than 17 million adults. With considerable variation among those countries, ranging from a low of about 1 percent in Norway to close to 4 percent in the United States, the overall estimate of 3 percent should be viewed as an underestimate.

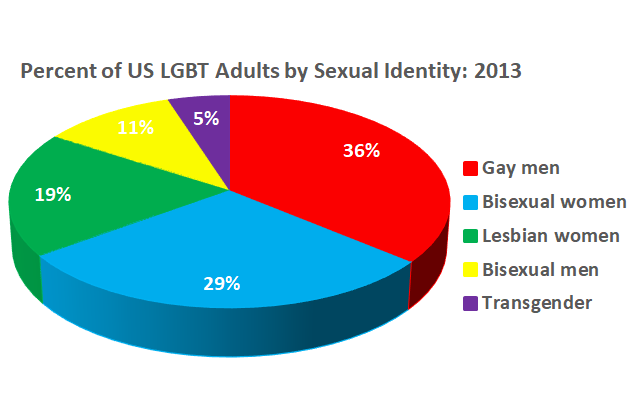

For many reasons, including privacy concerns, uncertainty, stigma and discrimination, determining the distribution of LGBTQ persons by sexual orientation or gender identity is a challenging undertaking with considerable uncertainty. One nationally representative survey in the United States in 2013 reported the estimates of the community's members: 36 percent gay men, 29 percent bisexual women, 19 percent lesbian women, 11 percent bisexual men, and 5 percent transgender. Some transgender adults in the survey described themselves as gay or lesbian.

Time-series sample surveys concerning sexual orientation have been conducted in Australia, and as observed in the United States, the proportions of Australian adults considering themselves homosexuals have risen since 2006. In addition, the proportions identifying as homosexuals varied by age with peaks of more than 6 percent for those in their 20s and lows of nearly 2 percent for those aged 50 years and over. However, those age differentials, also observed in other developed countries, may simply reflect a more accepting social milieu for younger homosexuals to disclose their sexual orientation.

The scarcity of accurate and timely statistics and studies on the LGBTQ population makes it easy to marginalize them, overlook issues affecting them and delay needed policy reforms. As is widely acknowledged, not being counted typically means one does not matter for policy purposes. Official government estimates of numbers and characteristics of LBGTQ persons are essential for relevant policy development and evaluation, informed decision-making and appropriate funding priorities. Without such statistics and studies, current policies and programs aimed at LGBTQ communities are likely to be misguided, inefficient and inadequate.

Joseph Chamie is a former Director of the United Nations Population Division and Barry Mirkin is the former Chief of the Population Policy Section of the United Nations Population Division.

Read more about the history of World Health Organization’s disease categories and declassification for sexual orientation.