Shelter for an Aging World

Shelter for an Aging World

.jpg)

MADISON, WISCONSIN: Changing demographics throughout the globalizing world, in particular an increase in the aging population and a decrease in birth rates, are disrupting housing markets.

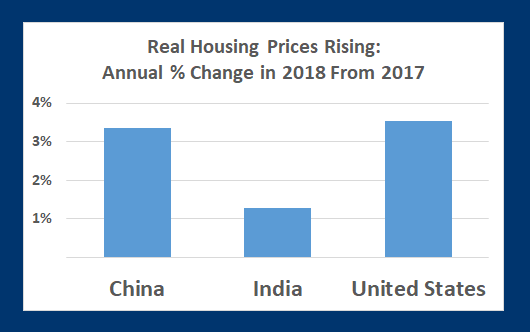

Since 1970, global median income per capita increased, with a few exceptions as in 2009 and 2015, and inequality also widened among and within nations. The International Monetary Fund’s Global House Price Index collapsed in 2008 before climbing again to reach pre-crisis levels. Due to these demographic and financial trends, household structures have changed with increased preference for smaller, shared living quarters and less home ownership worldwide. Analysts increasingly focus on mapping and predicting effects of globalization on housing markets and individual decisions.

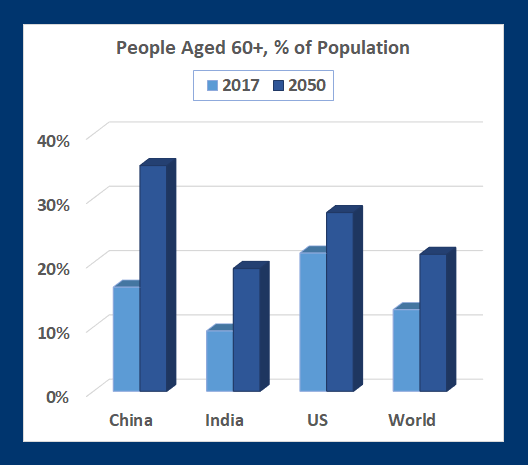

Countries at the forefront of globalization, namely the United States and China, as well as rapidly globalizing countries like India, expect their aging populations to double by the year 2050. Coupled with changes to the family structure, especially a childbirth rate nearly halved since 1950 and more dual-income households, decisions involving the housing stock are more complex than ever before.

The three behemoths in the world in terms of population – the United States, China and India – may share a common challenge: Their governments are not prepared for exponential growth in their graying populations. Out of the three, the United States could be most affected, as the primary mode of senior care in China and India is in-home care. If family support remains the top choice for senior care, this could insulate India and China from the adverse effects of lags in adequate public and private planning. In-home care involves family members covering the cost and accommodation of senior members. Citizens over age 65, as of 2017, represented 15 percent of the US population, 6 percent of India’s population, and 11 percent of China's population. About 65 percent of US elderly in need of assistance rely solely on family and friends, and non-family senior care is relatively new for India and China.

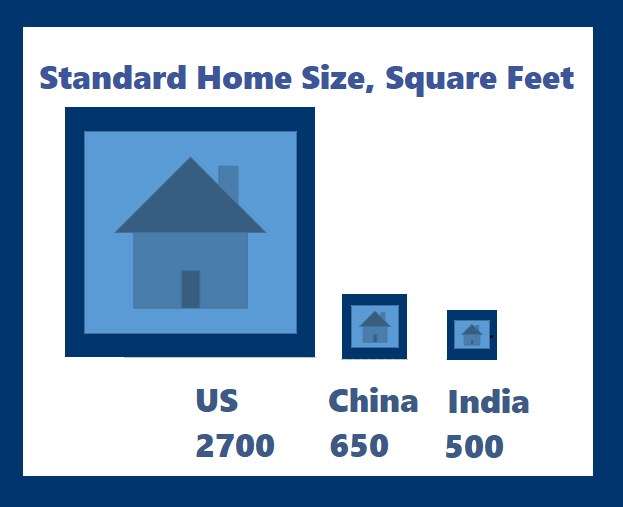

The average home size in the United States has nearly doubled since the early 1970s, with 2,700 square feet considered standard in comparison to India's 494 square feet and China's 646 square feet.

In the United States, the demographic of those aged 65 and above is predicted to swell, nearly doubling before 2040. The 2018 report by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University points out that "affordable, accessible housing located in age-friendly communities and linked to health supports is particularly in short supply." Challenges for seniors in need of housing include widening inequality, shrinking government subsidies for affordable housing and an imminent lack of feasible options. Detached, single-family homes and small apartments remain a popular choice for most adults aged 25 and above in the United States. With generally smaller families and a 30-year low in birthrates, according to the US Centers for Disease Control, smaller spaces have become more functional. Millennials also marry later and wait to buy homes. Demand has therefore shifted from large homes to individual rental units. Government at all levels provides tax breaks for senior housing, but regulations are few and health experts call for the private sector to make plans.

In Asia, the lack of planning may be less bleak with care of elderly parents deeply engrained in most cultures. China also confronts a majority-senior population, and a 2016 NCBI study found that 41 percent of the Chinese population aged 60 and older live with an adult child. Another 34 percent have an adult child living in the immediate neighborhood and 14 percent in the same county while 5 percent do not have an adult child living in the same county. Falling birthrates and shrinking family sizes, factors for China's housing market, have not yet reduced the practice of family care. While the wide-scale practice of live-in, in-home senior care will likely persist, private entities are showing interest in planned senior care. Potential investors view specialized senior care as a "sunrise industry," and try to overcome regulatory obstacles including an absence of detailed implementation rules and supporting policies from the government.

For India, in-home care remains the leading form of senior care and there is social stigma surrounding exclusive senior housing. The country anticipates housing challenges with a senior population some 240 million strong by the year 2050. Unlike the United States and China, wealth distribution is more polarized, with the top 1 percent of the population holding more than 70 percent of India’s wealth. Consequently, a small portion of the population enjoys high standards of living, options for housing and retiring in luxury. But the majority of the middle- and working-class households continue providing in-home care for senior citizens, and joint and multi-generational housing is the most common form for that socioeconomic category. Meanwhile, millennials in India follow global trends, trading ownership for access, showing a preference for leaner households and rental housing.

Globalization allows more cooperation among nations in addressing changing housing stock and financing. Between the first quarters of 2014 and 2018, for instance, Chinese private investors purchased about $1.4 billion of US housing properties targeting seniors. That investment has since stalled.

.png)

Globalization has also shifted cultural views on housing. Right to Housing is a United Nations–led movement that highlights shelter as a fundamental human right. Policies acknowledge increasing preference for planned, small, standardized housing designed for two adults. Examples of policies that acknowledge this trend involve eliminating property tax caps for seniors and encouraging efficient use of the housing stock through tax regulation.

Other factors for analyzing the interaction between a globally aging population and the housing market include advancements in medicine and living standards, among other variables, which contribute to greater longevity. One study predicts that in countries like the United States, with uncertainty over the availability of senior accommodations, people may stay in their own homes longer, in turn reducing available housing stock. If public and private sectors fail to meet demand, a perfect storm of trends could force greater reliance on multi-generational housing and shared living.

Asia led the way with shared multi-generational housing, and the United States and Europe may take that one step further with innovative forms of shared housing, including communal living in Europe, online matchmakers like Silvernest in the United States, and anecdotal reports of single seniors, unrelated, caring for and living with one another. These housing programs, both formal and informal, transcend differences as old and young, poor and wealthy, family members or not, live together under one roof. The transition, at least for millennials, could be seamless, as that generation has already embraced the concept of a "sharing economy" with ease.

Kanzuda Islam is a graduate in international relations and pre-Law. She has worked with notable NGOs that research shelter and human living standards such as BRAC.