#SiberiaOnFire: Crisis Communication in Russia

#SiberiaOnFire: Crisis Communication in Russia

NEW HAVEN: Effective communication with citizens, a basic expectation from any democratic government, is essential during a crisis. Most governments struggle to meet expectations and some like Russia may not address public concerns at all. Questions from the media, let alone outright criticism, rankle strong leaders. Cabinet members, business leaders and local authorities hesitate to speak out before the top brass issues an opinion.

.png)

Citizens no longer tolerate such a strategy, especially when information can spread around the globe in a matter of seconds. Russia received that message during summer of 2019 when massive forest fires spread throughout Siberia.

The wildfires began in Irkutsk Oblast, in late June, soon spreading to Krasnoyarsk Krai, Republic of Buryatia and Sakha Republic. By July 31, the fires had consumed 3 million hectares, or 11,500 square miles. Only then, President Vladimir Putin offered his first public statement about the fires and directed the Ministry of Defense to join the firefighting effort. The Kremlin website suggests that the statement made on July 31 was the president’s sole comment on the issue. This came on the heels of the July 29 statement from Mikhail Klinov, head of the Federal Forestry Agency: “We have more fires [sources] than in 2018, but with regard to the area, it is almost two times smaller than on the same date last year. There is definitely no crisis in the fire situation in Russia.”

Citizens look to public officials to calm, inspire and lead during such trials, providing regular detailed updates and recommendations. Barbara Reynolds, PhD, a consultant on international crisis and risk communications, identifies six basic principles of effective crisis communication, including credibility, empathy and competence. Leaders must be the first to address public concern and promote action, not waiting for chaos and speculation in social media.

In Russia, as polls suggest that citizens hold the president responsible for any issue that may occur during his term, building effective communication is of utmost importance in ensuring calm and political stability.

Summer of 2019 was already challenging enough for Russian domestic politics, with a number of events contributing to massive protests in Moscow. The election commission blocked more than 50 independent and opposition candidates from running for the Moscow City Election, triggering protests, but there was also broader discontent over several unpopular reforms and some law enforcement actions. “It is foolish to think that these demonstrations are for transparent elections or the admission of candidates,” said one 17-year old protester. “These demonstrations are in defense of elementary constitutional rights that would not be called into question in a democratic state.” More than 50,000 joined the protests, large by Moscow standards, to express frustration with cumulative government actions.

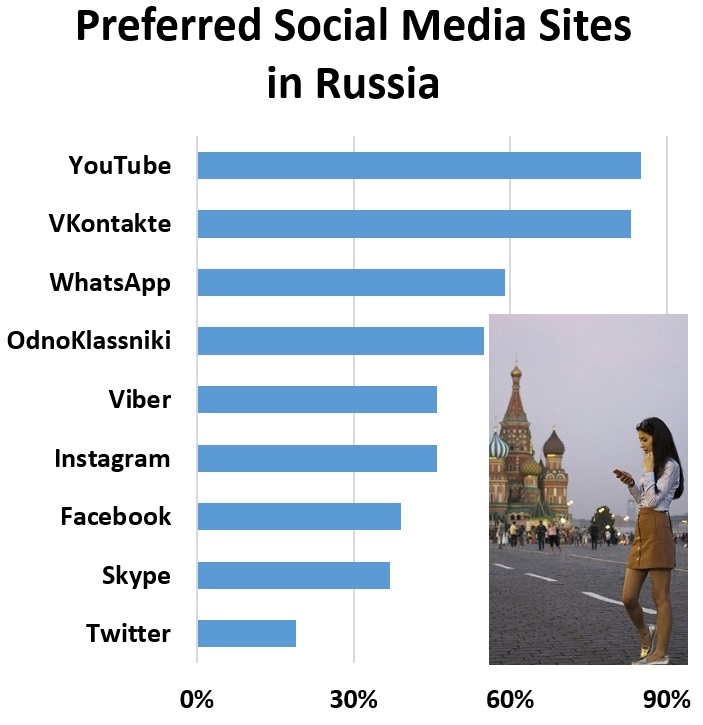

The protests began in mid-July, just as social media users began posting on the fires spreading from Siberia and the lack of government response. The news ignited public anger and skepticism. Opinion leaders, bloggers and celebrities posted terrifying images and statistics, urging public support for a petition requesting the federal government to address this issue. About 75 percent of Russians are on the internet and about half use social media, with these users described as among the most engaged in the world, especially on homegrown platforms like VKontakte and OdnoKlassnik.

A greater concern was that authorities failed to address the issue.

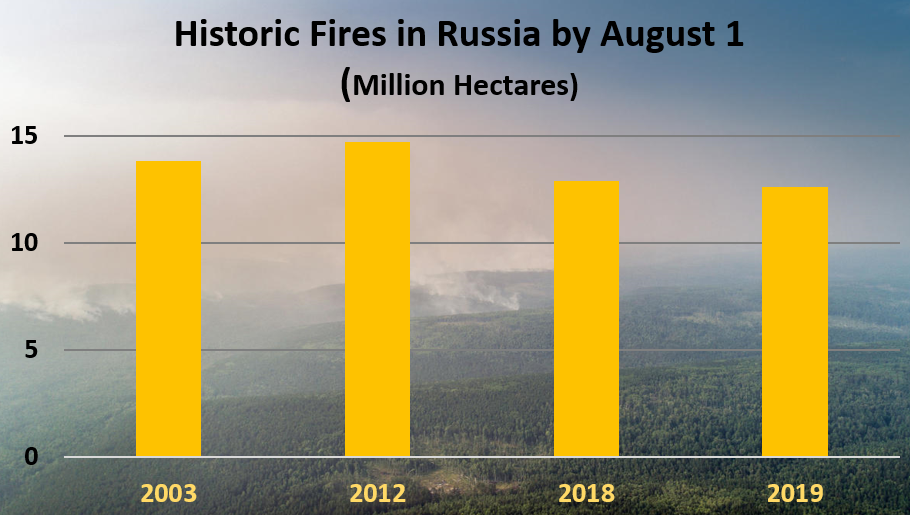

Of course, wildfires are not a new phenomenon in Russia. Every year fires affect millions of hectares of forests mostly in coniferous forests in the Siberian Federal District. The 2019 fires were one of the four largest hazards of this type for Russia in the 21st century, according to Alexey Yaroshenko, with Greenpeace Russia. By early August, areas of woodland three times that of Switzerland had burned. Smoke blanketed Siberia, extending to Alaska and Canada, in one of the most broad-scale natural disasters affecting millions of lives and leading to extensive environmental damage.

Amid minimal news reports and few official explanations, Russians demanded government action with more resources put into the firefighting operations. It is human nature to want to take action as smoke blanketed several densely populated regions, disrupting the lives of people living nearby. Social media messages relayed stories of human suffering, images of burned animals, ruined habitat and retrospective newscasts about the Russian government sending aid to tackle forest fires in other countries. By September 20, a petition on change.org demanding imposition of a state of emergency in Siberia had collected more than 1.2 million signatures. Instagram hashtags #SaveSiberia, #SiberiaIsOnFire and #FightSiberiaFires attracted thousands of followers. People all over Russia including public figures like performers Polina Gagarina and Basta engaged in the unprecedented movement and extended sympathy to Siberians.

Russian officials belatedly explained, according to news reports, that the government only dispatches firefighting teams if the cost of destruction outpaces the cost of firefighting. For all practical purposes, most governments tackle fires only when they pose direct threat to human lives and the costs of potential damage exceed costs of firefighting operations. The government did undertake some measures, including backfire techniques and cloud seeding to induce precipitation. But the territories burning in Siberia are remote, requiring trained operatives and special equipment, and costs would have far exceeded potential losses.

Otherwise, there is little consensus on how to manage such remote wilderness fires. Some experts point to positive outcomes of forest fires and negative consequences of firefighting operations in remote areas. In this respect, the Russian government’s actions were reasonable and justified.

Still, the government did not lead a campaign to explain and legitimize its actions. Local authorities handled virtually all communications even after concerns spread across the country. For Russia’s social-media users, a two-minute broadcast on national television praising the government is not enough. Informing the public and establishing mutual understanding require greater effort, especially during a time of unrest. Local communications are rarely enough. The public expects broad coordination and details on best practices.

The failure to address a complicated issue or crisis poses challenges for domestic policy and international affairs. Public representatives must lead in advocating their opinions and policies. Failure to build an argument, offer insights or share one's views allows others to misinterpret intentions. Efforts to provide ongoing communication during a crisis demonstrate respect for citizens, enabling public trust and smooth policy implementation. Not communicating is an action, too, one that can lead to misinformation and disruption in routines.

Natella Nuralieva is a Fox International Fellow based at the MacMillan Center at Yale University. She is a PhD candidate in sociology at Moscow State University, and her research examines problems of threat perception on individual, group and national levels from sociological perspective.