Prospects for Russia and Putin 4.0

Prospects for Russia and Putin 4.0

WARSAW: With a spring in his step and cool vigor that whips up domestic support, Russia’s President-elect Vladimir Putin prepares to march into the Kremlin’s St. Andrew Hall and be sworn in for his fourth term of office. Putin will need that energy and more in confronting the many political, economic, and social challenges that the ineffective regime is ill equipped to handle.

Over the past two decades, Russia has been transformed into a hybrid system that mixes an authoritarian structure with a free-market economy and great-power narrative. Putin secured a comfortable win in the March elections partly due to the anxiety running throughout society. Russians fear uncertainty, and for them, the leader at the helm of power for nearly 20 years is a familiar reference point on the political landscape.

Domestically, Russia will pursue its current course with several modifications. The elites will continue to treat state resources as loot, and Putin will play a central role in redistributing assets and disciplining the disobedient. Given the autocratic nature of the regime, Putin will have difficulties in giving up power in 2024. Hence, certain amendments to the form of government are likely. Before the next parliamentary elections are scheduled in three years, Russia’s regime model might shift from a presidential to the chancellor system with a strong prime minister and weak president, allowing Putin to overcome the limitation of presidential terms and remain in power indefinitely.

Executing this concept, Putin, 65, can be expected to delay the question of his successor. Yet a priority for Putin is finding the right heir who can ensure his personal security. Eventually he would need an absolute loyalist just as Boris Yeltsin found Putin in the late 1990s. The incumbent president is aware that any power vacuum in Russia would lead to chaos and internal crisis.

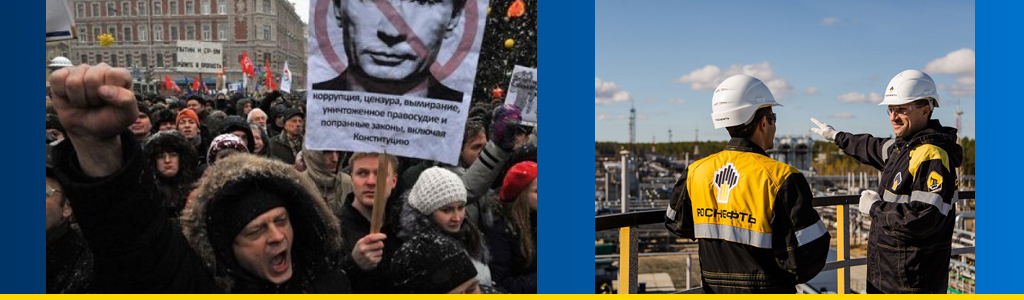

As the term of office proceeds, with few decisions shaping the political system’s succession, competing factions will come forward, and Putin’s position as an arbiter could be undermined. Until now, Putin has been the sole guarantor of balance among the Russian elites. The recent rise of Igor Sechin, Russia's most powerful oligarch as head of Rosneft and Putin’s friend, suggests that the delicate domestic equilibrium has started to shift.

More evidence of the shift is the emergence of a new generation of senior federal and regional officials. Since 2016 young technocrats have been filling posts of governors and administration managers. Putin replaces old leaders with a younger cadre even more loyal to and dependent on him. This process will continue and might in consequence limit the scale of corruption as more strict rules on extracting rents from the state and private business are set. Reducing corruption is key as a model of the Russian economy could be depicted based on three statistics: The energy sector generates 40 percent of the national budget, oil and gas account for 60 percent of Russia’s exports, and the state’s share in the economy is estimated at 70 percent. Whenever there are wide fluctuations in oil and gas prices, Russia is among the first countries to feel the negative consequences.

Economic stagnation is likely to continue as GDP growth oscillates between 1 and 2 percent, financial reserves dwindle, and dependence on energy exports remains heavy. The Russian ruling castes, accepting this outlook and a system that benefits them greatly, have no inclinations to disturb the status quo.

In April, the US Department of the Treasury imposed another tranche of sanctions against Russian officials, state corporations as well as private companies with links to the Kremlin. Since 2014 the United States has sanctioned nearly 200 Russian individuals and entities under various programs. Russia has thus far managed to deal with sanctions without serious perturbations to the economy. In the long run, however, technological and research cooperation with the West, and Washington in particular, must be restored for Moscow to develop sources of sustainable growth other than energy.

Russia, with virtually no tools to respond to Western sanctions, placed some economic hope in China. Yet Beijing has adopted a relatively neutral stance towards the clash between the West and Russia. The nation has no intentions or possibilities to compensate its struggling neighbor for the western markets, capital and technologies. China’s policy in this regard is unlikely to be amended.

Given Russia’s model of economy as well as the pressure of sanctions, it should be expected that Russian society pays the price for Putin’s adventurism in Syria and Ukraine. There is a strong likelihood that Putin will be forced to increase the retirement age, now 60 for men and 55 for women, and carry out reforms of the social care system, including further elimination of tax deductions.

As far as foreign policy is concerned, Russia’s increased assertiveness in power projection has marked Putin’s most recent term. Moscow’s directed activities at satisfying its global aspirations, consolidating the society around its leader, and stimulating the transformation of the liberal international order into a new edition of concert of powers, where states fiercely compete in the name of national interest. In many respects the Kremlin has achieved its goals of prominence on a global stage, at least in the Middle East. But Western allies’ recent decision to expel more than 120 Russian diplomats in relation to the nerve agent attack in the United Kingdom signaled the West’s unity.

Putin’s fourth term could likely sharpen antagonism between Russia and its adversaries in the West, and Moscow will be opportunistic in its approach. On the one hand, it will continue the policy of freezing war in Ukraine and masquerading as a protector of peace. On the other hand, Russia will count on the fatigue amid the Western bloc while trying to secure new geopolitical assets in Syria or the Balkans without open confrontation. The Kremlin will also target individual EU and non-EU countries to divide both NATO and the broader Western alliance, for example by engaging Hungary or Japan, with the latter hoping to regulate territorial disputes with Russia.

The 2018 World Cup in Russia, starting June 14, might serve as a temporary pause for disputes between Russia and the West. Yet the conflict in Ukraine, after the 2014 Olympics in Sochi, shows that the globe can expect aggressive actions to resume after a sports-related de-escalation.

Russia is a country with great history and potential, but bleak prospects. At his state-of-the-nation address delivered in March, Putin – with nostalgia in his voice – enumerated the geographic, military, and economic losses Russia endured with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, to which he still refers as the greatest tragedy of the 20th century. And modern-day Russia still glorifies the historic narratives of Soviet achievements during World War II. A 2017 Levada Center poll revealed that 38 percent of Russians think that Joseph Stalin, more so than Putin, is worthy of the title of Russia’s greatest ruler.

With the next six-year term and Putin in charge, Russia can expect no significant economic reforms or political liberalization. Instead, he will develop a model of succession or preservation of power within his own narrow circle, and any forward-looking strategies will give way to plots aimed at conserving the system.

Michał Romanowski is a Eurasia expert with The German Marshall Fund of the United States in Warsaw.