The South – Ultimate Pandemic Victim

The South – Ultimate Pandemic Victim

STOCKHOLM: By definition, a pandemic knows no boundaries and is inherently limitless. No country escapes, and crises cascade. With the world economy in freefall, countries have acted to protect their population, but equal determination is required for unparalleled multilateral cooperation. The wealthiest nations have launched gigantic financial packages to mitigate the effects on their own economies, but the consequences for the global South have raised only marginal concern. This is a recipe for disaster.

In a few short months, the virus has placed a hyper-globalized world in a state of paralysis. For the developed world, disease struck first followed by economic disaster. The reverse is true for developing countries, hit hard financially due to the global downturn, followed by the onslaught of Covid-19.

The world has radically reduced poverty – the World Bank estimates that less than 10 percent of the world’s population lived on less than $1.90 a day in 2019, down from more than a third in 1990 – while inequality has grown. For the first time since 1998, poverty rates will rise as the global economy falls into recession and the ongoing crisis will erase almost all the progress made in recent years. The World Bank estimates, conservatively, that up to 60 million people will fall into extreme poverty in 2020, and the World Food Programme estimates that 265 million may suffer from crisis levels of hunger – an increase of 130 million over pre-pandemic levels. Public debt will grow, and government revenue will decrease, with consequences not least for already weak and underfunded health systems.

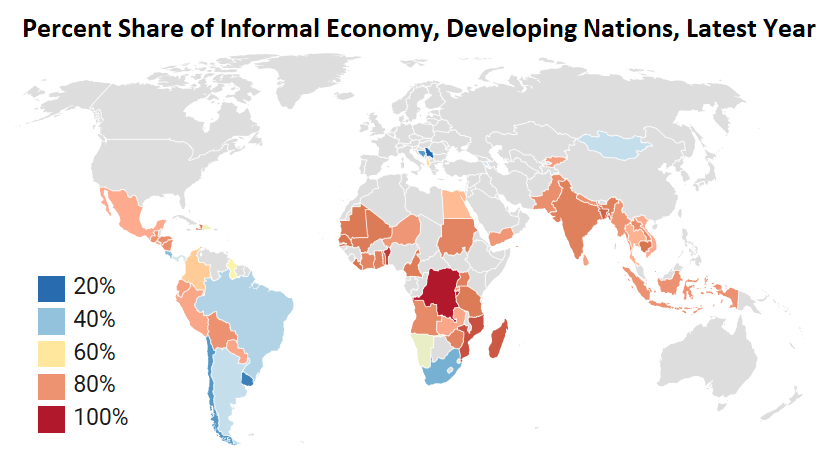

As developed economies focus on their needs rather than wants, many middle- and low-income countries, deeply integrated into the global economy and its value chains, will struggle. The World Trade Organization expects global trade to decline by between 10 to 33 percent due to the corona pandemic. In Bangladesh alone, 4 million garment workers, mostly poor women, have lost or risk losing their jobs. The same goes for Cambodia, another country with a huge garment industry based on demand from wealthy countries. For other countries, the vital tourist industry, employing tens of millions, is near dead. Mexico and Turkey rely on tourism for 15 and 11 percent of GDP, respectively. Foreign capital suddenly flows in the opposite direction, out of the countries.

Tens of millions of migrant workers and their families are exposed. Many migrants send money home from their work as construction workers, maids, drivers in richer countries – a lifeline. Such remittances account for a hefty percentage of gross domestic product – 20 percent in El Salvador and Honduras, 30 percent in Haiti, 10 percent in the Philippines and Senegal – often much more than foreign aid. These transfers dwindle with profound consequences.

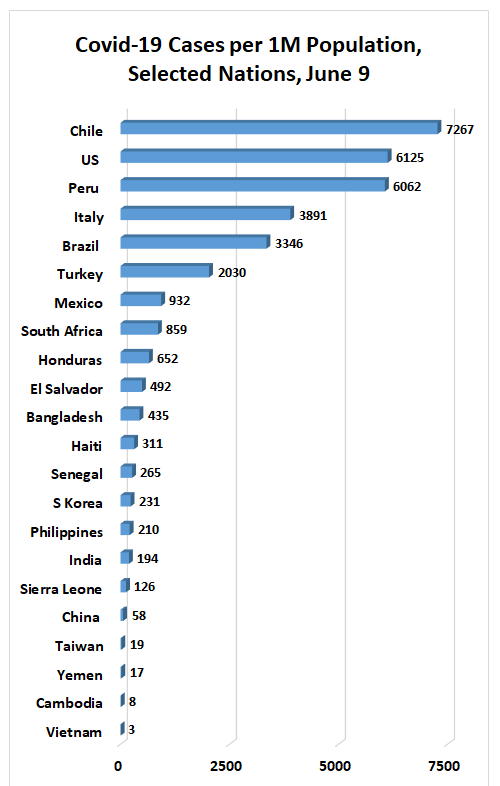

Latin America is the epicenter in the South. Brazil is the worst affected country in the developing world with total deaths exceeding 38,000, mass graves and a president in denial. Peru and Chile report some of the world’s highest infection rates, with more than 6,000 and 7,000 cases per million people, respectively. And no country in the region will escape the devastating economic impacts.

.png)

War-torn Yemen and refugee camps like the one in Bangladesh, with more than 1 million Myanmar-displaced Rohingyas – lacking clean water and space for social distancing, let alone “protective equipment – are at the brink of losing control over Covid-19’s spread.

Just over 50 million, or less than 5 percent of Africa’s population of nearly 1.4 billion, consists of people over age 60. Given the vulnerability of the elderly, that is an advantage for the coronavirus, but malnutrition, reduced immune systems, malaria, widespread HIV, disrupted vaccinations due to lockdowns and basic lack of resources weaken the population’s resilience. Some African countries have fewer than 100 ventilators. Sierra Leone has one ventilator for 7.5 million inhabitants and 10 nations have none at all, reports the New York Times. Western countries have drained the market.

Some countries, such as South Africa and India, have taken drastic preventive measures with the most vulnerable inevitably hit first. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi introduced a national curfew, without warning, at the end of March. Tens of millions in the extensive urban informal sector tried desperately to reach their hometowns, increasing the risk of spreading infection. The virus could thrive in the dense slums of Mumbai and Cape Town is emerging as Africa’s covid epicenter.

China, the origin of the virus and the pandemic, bears undeniable responsibility. It managed, with the full force of the party-state, to contain the infection within its borders. But transparency and early notification were lacking. The government silenced Li Wenliang, the doctor who sounded the alarm in late December, forcing him to sign an assurance not to spread "false rumors.” Despite the experience of SARS in 2003, the sale of live animals in crowded city food markets continued. Traditions run deep, and so does Chinese nationalism. The blame lies elsewhere.

A number of other East Asian countries have fared, partly due to experience with SARS, much better than Europe and the United States. South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam immediately recognized the imminent danger, and through vigorous testing and tracing managed to minimize Covid-19 infections. No success is guaranteed, however, as a new cluster emerging in South Korea in late May shows.

A heavy responsibility rests on Western democracies for their tragically slow and inadequate response. Pandemic management should be an essential part of contingency planning for every country, especially as climate change increases risks. Despite dramatic evidence with lockdown of the entire province of Hubei on January 23, population 60 million, Covid-19 still took too many countries by surprise.

In 2019, close to 140 million Chinese traveled abroad, including 4 million to Italy. But in Lombardy, such risks were not understood. More than 16,000 died there compared with, officially, 3,200 for Hubei.

The pandemic epicenter shifted from southern Europe to the United States. President Donald Trump, focused on his reelection, infallibly blamed the World Health Organization and China, stepping back from international leadership and announcing plans to leave the World Health Organization. The global research community otherwise cooperates as never before in real time to produce a vaccine, but international cooperation, especially between the US and China, is a zero-sum game, including fabricated accusations and counter-accusations of “vaccine nationalism.”

In mid-April, the G20 countries agreed on a time-bound suspension of debt repayments for the world's poorest countries: 17 European and African leaders – including Germany’s Angela Merkel, France’s Emmanuel Macron and South Africa's Cyril Ramaphosa – launched an appeal to support Africa. On June 1, a new appeal was launched by, among others, former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown stating, “Without further G20 action, the pandemic-induced recession will only deepen, hurting the world’s poorest and most marginalized people the most. Because G20 represents 85 percent of global GDP, it has the capacity to mobilize resources on the scale required – and its leaders must do so immediately.” Such Initiatives, while welcome, are just a start. The International Monetary Fund suggests that emerging markets and developing countries need $2.5 trillion to overcome the crisis, with only a fraction allocated so far.

History will judge the post-corona world by how it mobilizes awareness and resources to prevent irreparable harm for the global South and obvious risks of recoil effects. Otherwise, Covid-19 will go down in history as the pandemic of denials and rich-world shortsightedness.

The "normalcy” of the last few decades is unsustainable. Denying the treacherous connections between climate change and increased frequency of pandemics, between inequality and desperate migration, would be the ultimate folly.

Börje Ljunggren is former Swedish Ambassador to China, author of Den kinesiska drömmen – Xi, makten och utmaningarna, The Chinese Dream – Xi, Power and Challenges, 2017, and associate, Harvard Asia Center.