US Retreats From Its Lead on Epidemic Preparedness

US Retreats From Its Lead on Epidemic Preparedness

NEW HAVEN: As a major innovator, donor and active implementer of health programs worldwide, the United States is among the major pillars in global health. The US government has led in targeting many pressing global health challenges including tuberculosis, HIV, reproductive health and the fight against epidemics.

Swift attention and action from providers and researchers in developed nations prevent local events from becoming global epidemics. Such preparedness is among the most urgent challenges facing the international community in an interconnected world.

Budget cuts proposed by the Trump administration, as well as criticism directed toward foreign aid and multilateral engagement, could reduce the US leadership role in global health. Early budget blueprints from the administration proposed big reductions to the underlying US health infrastructure that responds to disease outbreaks: 25 percent for US State Department programs targeting health issues; 17 percent for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including a 10 percent cut for the agency’s office of public health preparedness and response; and 18 percent for the National Institutes of Health, the nation’s medical research agency. Institutions like the Fogarty International Center, which builds partnerships with countries abroad and trains health researchers from around the world, would be eliminated.

The entire world, populations in low-income countries and the American people, will suffer. In an increasingly interconnected world, epidemics are more routine than unusual – including SARS in Asia and Canada, cholera in Zimbabwe and Haiti, various flu pandemics, Middle East respiratory syndrome, and Ebola and Zika in recent years.

A strong frontline of skilled medical researchers and providers pinpoint outbreaks and communicate updates to monitor and stem the spread of diseases that can disrupt the lives and well-being of thousands of people in a matter of weeks. Most political leaders understand that viruses and other diseases do not stop at national borders and that global health is a humanitarian duty, one with strategic implications. International cooperation, responding to disease outbreaks at the source as soon as they emerge, is necessary to protect citizens around the globe.

Optimism ran high in the 1970s that infectious diseases would no longer threaten humanity due to progress in medicine and hygiene. But rapid increase of travel and international commerce, ongoing environmental degradation as well as population growth and urbanization as global megatrends are ensuring that diseases spread far and more quickly than ever before.

Consider the most recent major health crises:

· Massive in scope and fast-spreading, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa killed more than 11,300 people within 18 months. It weakened health systems and took a dreadful toll on the countries’ economies and social systems.

· The Zika virus, a mosquito-borne disease causing brain malformations in newborns, spread rapidly in the Americas and other parts of the world.

· Currently, public health experts are highly worried about one of the deadliest strains of avian flu spreading in China and causing a surge in human infections.

These are only some of the most prominent examples of disease outbreaks that have alarmed and put the global health community on high alert.

Researchers have recognized and addressed the threat of fast-moving infectious diseases since the early 2000s. Governments, international organizations, NGOs and private actors have created numerous policies and instruments to prepare for epidemics. Constant vigilance and investments are required to monitor threats that can emerge anywhere, and the current level of preparedness remains inadequate.

The US government has played a major role in first raising and emphasizing the issue of epidemic preparedness. Washington was among the first countries that emphasized the challenge by listing infectious diseases as a high-ranking national security threat, for example, in the 2000 report of the National Intelligence Council. The United States also crafted policies and a health infrastructure aiming at epidemic response both at home and, to a lesser extent, abroad. As a major supporter for reforming and strengthening the International Health Regulations in 2005, Washington pushed for improved capabilities to detect, assess and respond to health crisis. The US announced the Health Security Agenda in 2014 to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and US health institutions responsible for domestic health surveillance like the Centers for Disease Control, the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health are renowned for providing technical assistance and training for health professionals from all over the world.

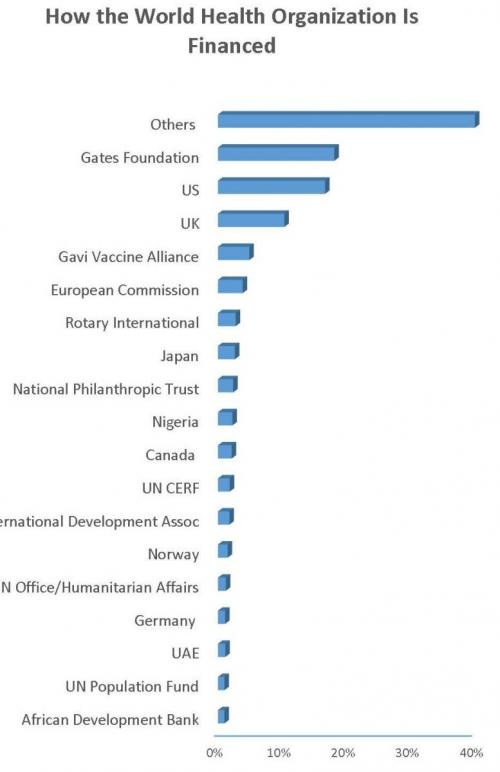

Team effort: A mix of private foundations and nations around the globe fund the many programs of the World Health Organization (Source: WHO)

But “America first” principles, embodied in Donald Trump’s vow in the budget blueprint to “keep […] more of America’s hard-earned tax dollars here at home,” stand in sharp contrast to this approach. His critical view toward foreign aid, largely viewed as charity, ignores key lessons learned by the international community in responding to recent infectious disease outbreaks: Epidemics can be best contained at their source, and prevention is better than reaction.

Caregivers everywhere must be trained and ready to report unusual events, and investments in the health systems of low- and middle-income countries are the first line of defense when it comes to the prevention of outbreaks. Proposed budget cuts would contribute to less vigilance, preparation, training and a slower response.

International diplomacy, multilateral coordination, and concise public communications are critical during large-scale disease outbreaks in order to control the situation. News reports suggest that the Trump administration is sidelining career professionals in the US State Department. Impulsivity, irritable reactions, delayed or confusing communications, and impatience with multilateral approaches could complicate the public response for the next epidemic. Relaying accurate communications about the nature of the disease and prevention in an era of “fake news” and “alternative facts” could be the greater challenge.

In addition, US preparedness is in question with key positions of critical public health agencies, pivotal for researching and respoding to infectious diseases, still vacant four months into the administration. The Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention currently has no permanent director, and many positions are yet unfilled at the Department for Health and Human Services along with sub-cabinet positions.

The Trump administration does propose a Federal Emergency Response Fund for disease outbreaks, but details about the fund’s size and source are unclear.

We are living in one of the most dangerous times in terms of the spread of diseases, and the world relies on cooperation with fast and accurate reporting along with research on prevention, treatment and vaccines. An “America First” philosophy does not bode well for global health, and the outlook for the US leading role in strengthening epidemic preparedness is rather dire.

Still, dangerous disease outbreaks have increasingly gained attention with the start of this century from many actors and organizations apart from the US government. The topic is high on the agenda of Germany’s G20 presidency and the World Economic Forum – and disease prevention is prominently embraced by wealthy donors like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as well as international conferences like the Munich Security Conference.

Recent health crises have alerted and enabled a large force for strengthening capabilities to detect and respond to epidemics worldwide. But make no mistake, the US government’s restraint in outbreak preparedness is a major setback for global health policy.

Daniela Braun is a 2016-2017 Fox Fellow at Yale University and a PhD candidate with the Free University Berlin whose research centers on the intersection of health and security. Her dissertation investigates the role of military assistance in a health crisis response. Her experience working on topics related to German security and defense policy as a program officer at the German Council on Foreign Relations, and she is also a member of the extended board of the German chapter of Women in International Security.