US Retreats From Syria and the Middle East

US Retreats From Syria and the Middle East

LONDON: US President Donald Trump’s showboating on the dramatic assassination of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi cannot mask the more enduring result of his capricious decisions during October’s turmoil in North-eastern Syria, strengthening the Syrian regime and its allies, notably Russia.

Turkey’s military incursion into northern Syria, controlled by the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Defense Forces, or SDF, has reset the standing of the players in the Syrian civil war, in its ninth year. The winners are the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Turkey and its allied militia of Syrian rebels, Russia and Iran. The losers are the United States, once protector of SDF fighters, and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. The chance of regrouping by escapees from among 6,000 ISIS jihadists held in SDF-run detention camps have diminished in the aftermath of al-Baghdadi’s death.

Trump’s handling of this crisis – created by his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s offensive, code-named Operation Peace Spring, to remove Kurdish forces from Turkey’s 440-kilometer southern border and transfer up to 1 million of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees to the 32-kilometer wide strip – highlighted his multiple personality and policymaking flaws. In his self-created parallel world, Trump exercised his “great and unmatched wisdom” – sharp contrast to the down-to-earth character of Russian President Vladimir Putin who is inclined to make calculated geopolitical moves.

For years, Turkey watched with alarm the growing affinity between the SDF and the Pentagon. Many SDF Kurds are also members of People’s Protection Units – Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, or YPG – an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ party fighting an insurgency against the Turkish state since 1984, first for independence and then for autonomy, which has consumed 40,000 lives.

Fear of Kurds’ quest for self-determination, materializing as the sovereign state of Greater Kurdistan covering contiguous Kurdish-majority parts of Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria, has existed among the rulers of these countries for decades. Indeed, the autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan that existed under Western protection from 1991 onward held a referendum in September 2017 which showed 94 percent backed independence. The central government in Baghdad aided by Tehran used force to reassert authority, thus ending the region’s autonomous status.

Given this, Iran is pleased to see the Kurdish-dominated Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria compelled to reconcile itself with Assad’s regime at the behest of Moscow to resist Turkey’s onslaught. With the Syrian president withdrawing forces in 2013 from the sparsely populated region, occupying a quarter of Syria’s territory of 185,000 square kilometers, to curb the mounting armed opposition in the populous southwest, Kurds had little reason to actively oppose Assad.

The roots of Washington’s Kurdish alliance go back to late 2014 when the Kurds ended Islamic State’s siege of Kobane, with the assistance of the Pentagon’s arms and airstrikes. The Kurds went on to win a string of victories against ISIS jihadists. Along the way these fighters absorbed non-Kurdish groups, changed their name to the Syrian Democratic Forces and saw their ranks swell to 60,000. In the six-month long battle from April 2017, they expelled ISIS from its capital of Raqqa with coordinated help of the United States and lost an estimated 11,000 fighters.

Little wonder that US politicians and pundits decried Trump’s 6 October decision to withdraw 1,000 commandos who had provided air support, ground assistance and training for Kurds against ISIS as a great betrayal. The move was viewed, rightly, as creating a vacuum to be filled by Russia and Assad’s regime. Trump tried to make amends with a stern letter to Erdoğan on 9 October: “History will look upon you favorably if you get this done the right and humane way. It will look upon you forever as the devil if good things don’t happen. Don’t be a tough guy. Don’t be a fool!” Turkish presidential sources told the BBC that Erdoğan “received the letter, thoroughly rejected it and put it in the bin.”

After meeting US Vice President Mike Pence in Ankara, Erdoğan agreed to a “pause” of five days in his offensive. Trump claimed it was “a great day for civilization” that would save “millions of lives.” The total population of the north-eastern region is 2.3 million, one-tenth of the pre-war figure for Syria.

After a cascade of criticism over Turkey’s incursion, on 14 October Trump re-imposed 50 percent steel tariffs on Turkey, authorized sanctions against current and former officials, and halted negotiations for a distant $100 billion trade deal.

On 16 October, the House of Representatives condemned his abandonment of Kurdish forces in Syria, 354 to 60, with two-thirds of Republicans joining Democrats. This vote came hours after Trump described his original decision as “strategically brilliant” at a news conference.

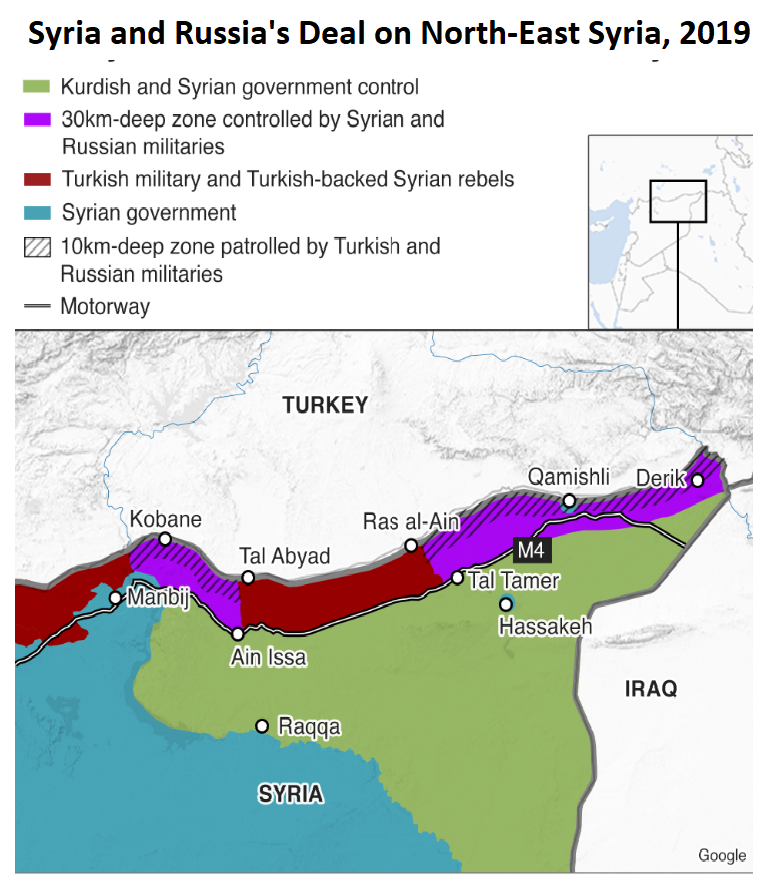

Six hours of talks between Erdoğan and Putin on 22 October in Sochi defined the contours of Turkey’s “safe zone.” along its southern border. Turkish troops will remain in areas seized since the offensive; Russian forces and the Syrian army will control the rest of the frontier, effectively fulfilling Erdoğan’s aim at Putin’s discretion.

The next day Trump declared the Syria ceasefire as “permanent” and lifted token sanctions on Turkey. “Let someone else fight over this long-bloodstained sand,” he declared. Then, as before, he tried to make amends. He announced a plan to keep 500 US troops to protect oilfields in the area and tweeted that the United States just “took control over oil in the Middle East.” Fact-checking is enough to prick Trump’s make-believe bubble. At 25,000 barrels per day, Syria’s oil output is puny in the global total of 100 million barrels per day. And in February 2018, state-owned Rosneft of Russia acquired exclusive oil and gas exploration and production rights in Syria.

Putin has combined an impressive sense of timing with optimum use of Russia’s strategic cards. He intervened militarily in Syria in September 2015 to save Assad from a defeat in the civil war while wisely refraining from committing ground troops. That left intact Russia’s friendly relations with Iran dating back to 1997. Gulf rulers, sensing new power in the Middle East, made beelines to meet him in Moscow or Sochi.

With Russia producing as much oil as Saudi Arabia, leader of OPEC, King Salman sought Putin’s cooperation in cutting output to keep prices buoyant. Acting as leader of non-OPEC oil producers, Putin obliged. Salman’s subsequent state visit to Moscow in October 2017 laid a firm foundation for cordial Russian-Saudi relations. Two years later, in the midst of turmoil in North-eastern Syria, Putin paid a return visit to Riyadh. Saudi Aramco agreed to acquire a 30 percent stake in Novomet, a Russian oil equipment supplier, and the Kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund signed $600 million deal to invest in Russian aircraft-leasing business. This helped Russia to offset slightly the negative consequences of Western economic sanctions following its 2014 annexation of Crimea.

In the neighboring United Arab Emirates, the air force painted the colors of the Russian flag in the sky as Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed greeted Putin at the Abu Dhabi airport. More than 3,000 Russian companies are registered in the UAE, which welcomed more than 900,000 Russian tourists last year.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE are among the 13 countries keen to purchase Russia’s S-400 air defense missile system, superior to America's Patriot and THAAD missiles. An advanced, mobile, surface-to-air defense system of radars and missiles of different ranges, it is capable of destroying targets as varied as stealth bombers, cruise missiles, precision-guided munitions and more. Each battery normally consists of eight launchers, 112 missiles and command-and-support vehicles.

Defying US threats of sanctions, Erdoğan signed a contract for the purchase of several S-400 missile systems, two of which have been received and deployed in Turkey, a NATO member.

In the chronology of the geostrategic Middle East, situated at the intersection of Asia, Europe and Africa, the killing of al-Baghdadi will merit nothing more than a footnote in a chapter outlining America’s retreat from the region and the advance of its challengers.

Dilip Hiro is the author of After Empire: The Birth of a Multipolar World (Nation Books, New York). His latest and the 37th book is Cold War in the Islamic World: Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Struggle for Supremacy published by Oxford University Press, New York; Hurst Publishers, London; and HarperCollins India, Noida. Read an excerpt. Read a review. Listen to a podcast interview with Hiro.

This article was posted 30 October 2019.