Want to Build a 3D Printer? Look No Further Than Your Electronic Junkyard

Want to Build a 3D Printer? Look No Further Than Your Electronic Junkyard

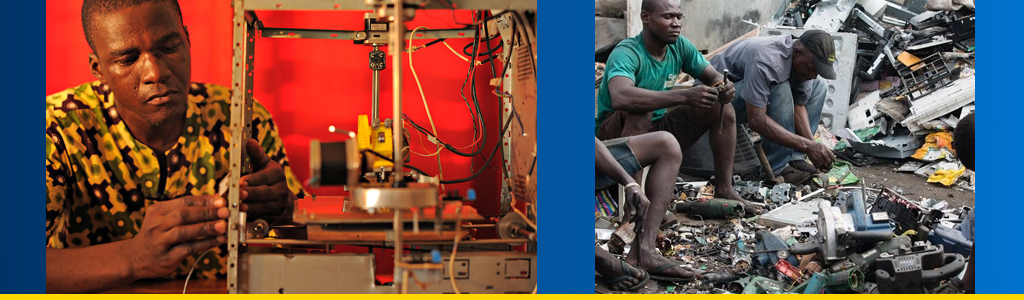

LOME: In 2013, Togolese inventor Afate Gnikou built a 3D printer entirely out of recycled electronic waste. The 34-year-old had become consumed by the idea of creating his own version after seeing a 3D printer assembled at the inaugural edition of Fab Lab – a digital fabrication workshop-in Lome, the capital of Togo, in August 2012.

A small country in West Africa, with a population of about 7 million, Togo’s main industry remains subsistence agriculture, on which more than half of the Togolese continue to depend. Young Togolese under the age of 35, representing 75 percent of the population, confront a severe unemployment challenge. Unemployment rates for the entire country hover around 6.5 percent, but are near 10 percent for young adults. Under-employment is estimated at more than 20 percent. The Togolese economy is robust, reports the World Bank, but struggling due to a recent slowdown in neighboring Nigeria and a widening deficit. More than half the population lives below the poverty line.

In Togo and other countries struggling to develop, the latest technological advances are out of reach. Constructing new devices with bits and pieces from discarded units may not eliminate considerable poverty or the large amount of waste, but e-waste recycling could foster broader innovation, education and exploration, solving a plethora of socio-economic problems.

Workshops like Fab Lab offer both education and entertainment. Gnikou is a geographer by training and tinkerer in electronics and bricolage by necessity – experienced in putting together small electrical cars and car doors, as well as repairing cell phones for people in his neighborhood, all helping him earn extra income to survive. A friend urged him to attend the workshop featuring an entrepreneur from Europe who would assemble a new technology. Driven by curiosity, Gnikou attended the Fab Lab as an observer. The speaker put together a 3D printer during the workshop with an installation kit brought from France, including all required hardware and software that ensured the final device was operational.

Gnikou became enthralled, immediately envisioning the potential for his country where industry accounts for 5 percent of the labor force. Such a device could bolster technological innovation and creativity, allowing entrepreneurs to create affordable, professional and rapid prototypes to ensure that their inventions would function well and reliably. A 3D printer could enable consumers to purchase locally-made products tailored to their needs rather than standardized, imported commodities from either Western countries or China. Such printers could ultimately propel Togo into the technological markets of West Africa and eventually the globe. Gnikou also recognized that the printer would be environmentally friendly by increasing reuse of discarded electronics available in local dumps.

After the workshop, the 3D printer was displayed in an education center for the next year, though December 2013. Gnikou visited the display once a week studying the device and trying to figure out its assembly and how it operated. Installation kits were unavailable in Togo, and Gnikou was determined to replicate the 3D printer from scratch using readily available e-waste. He set up an open-air workshop in the small courtyard near his home, shared by several neighbors. His laboratory consisted of a large table and chair, the area protected from the scorching sun by a plastic cover tied to nearby trees.

Gnikou had several old desktop computers at home. He tore them apart to use some of the elements, including the overall frame and the electrical wiring. He spent six months of trial and error as well as reading instructions on the internet and watching YouTube videos until he eventually assembled his own 3D printer. The most difficult yet also exciting part, he confessed, was figuring out how to assemble the extruder, a key part of 3D printers that melts the material and moves back and forth, creating layers to mold the desired object. After extensive online reading about printers, the young inventor managed to create his extruder using old plastic copier gear.

His device attracted substantial international recognition, including the prize for technological innovation during the 10th International Conference of Fab Lab in Barcelona in 2014. He continued working to improve his device, producing several smaller, more robust and efficient models. By 2015, he created a second prototype, again using parts of discarded computers and printers mostly from the electronic waste market near Lome’s Port.

Many old consumer electronics arrive at this port, shipped from Western countries, sometimes illegally. Globally, more than 40 million tons of electronic waste are generated every year, comprising around 70 percent of total toxic waste. Tracking is imprecise, and government regulators in the developed nations concede that exporting used electronic devices, most to countries in West Africa and Asia with less stringent environmental regulations, can be less costly than discarding at home. With 85 percent of the e-waste generated at the regional level, West Africa faces a growing problem of its own making. Most of the e-waste is burned to prevent unmanageable stockpiles that contaminate the soil with hazardous substances like lead and mercury. The smoke from burning is equally dangerous, though, containing dioxin, heavy metals and other elements threatening human and environmental health. Despite this, only about 15 percent of e-waste is recycled globally. In December, the United Nations issued a report recommending greater global collaboration on e-waste.

Since creating his 3D printer, Gnikou has found multiple uses for the device. One of the first was printing inexpensive prototypes of designs by local entrepreneurs. For instance, his device helped print multiple prototypes for an anti-theft device created by three young Togolese men based in Lome. The prototype helped resolve production flaws and moved that invention to its final stages. That anti-theft product addresses a specific need for the many West Africans who rely on motorcycles for transportation. But the small vehicles are often stolen, and according to official statistics, more than 7,000 motos were stolen in 2015 alone. The anti-theft invention includes an integrated GPS system that tracks the stolen vehicle and allows owners to cut their vehicle’s engine.

While printing models and prototypes are helpful for emerging Togolese innovators, such work still did not provide Gnikou a living wage. So he shifted his focus to training others on how to create and use their own 3D printers. In December 2016, working with EcoTec Lab – an innovation center for ecology and integrated sciences – Gnikou co-organized the Togo MakerFest, a two-day do-it-yourself manufacturing event and led community sessions on building a 3D printer.

Gnikou is not giving up on inventing or Togo. He continues striving to define the role of the 3D printer for the Togolese market and make plans to improve its functioning. Among his upcoming projects is to produce the special plastic material needed for the 3D printer by recycling available plastic in Togo. In particular, he wants to recycle plastic bottles that end up covering the streets and beaches of Lome, often blocking sewage systems.

In a country where the literacy rate is below 65 percent, his efforts reaffirm of the value of technology, education and exploration and a can-do spirit.

Raluca Besliu is a freelance journalist focused on women’s and children’s rights, refugee and human rights issues, and peace and post-conflict reconstruction. She graduated from the University of Oxford with an Msc in Refugees and Forced Migration after studying international affairs at Vassar College. She founded the nonprofit organization Save South Kordofan. Follow her on Twitter.