A Trade Love Triangle

A Trade Love Triangle

NEW HAVEN: The European Union is forced to rethink its position in a changing world order between the United States and China. Despite lingering suspicion about Chinese goals for the continent, increasing antagonism on trade from the United States may move other economies closer together.

For example, the 21st EU-China Summit surprised many strategists with the two sides managing to reach joint agreement, signaling that Europe may not automatically follow the US lead in attempts to contain China’s rise. Chinese leaders suspect US pressure on trade is designed to block China’s emergence. The joint statement from the summit does not reflect the view of “China as systemic rival,” as suggested by a European Commission document published in March and instead signals that the two economies preserve a sense of partnership, committed to joint efforts to smoothing over differences and finding common ground.

The EU is China’s biggest trade partner, and China is the EU's second biggest trading partner after the United States. Under the joint agreement, the two sides will continue to forge synergies through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, BRI; the EU strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia as well as EU Trans-European Transport Networks. China and the EU are at a crossroads, with the EU showing a tougher stance on China’s business practices and leadership of both sides anticipating progress with a new investment access deal. To sustain momentum, the EU-China relationship must be built on a rules-based multilateralism, accompanied by articulation of specific goals and specific guidance for achieving progress.

The EU and China have experienced a honeymoon with a multidimensional relationship. They established formal diplomatic ties in 1975 and have committed to comprehensive strategic partnership since 2003. Cooperation is indispensable. Despite the 2010 dispute on solar panels, the 2013 EU–China summit still put forward the “EU–China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation,” which promised to strengthen bilateral cooperation through sectoral dialogues. Business and trade as priorities largely shaped relations. China accounts for about a fifth of EU goods imports and more than a tenth of its exports. About 8 million people travel between the two places, and the past four decades have witnessed a 250-fold increase in trade between the two sides. China and the EU also express strong commitment to multilateralism, the Paris Agreement on climate and non-proliferation issues even as the United States turns its back to global governance.

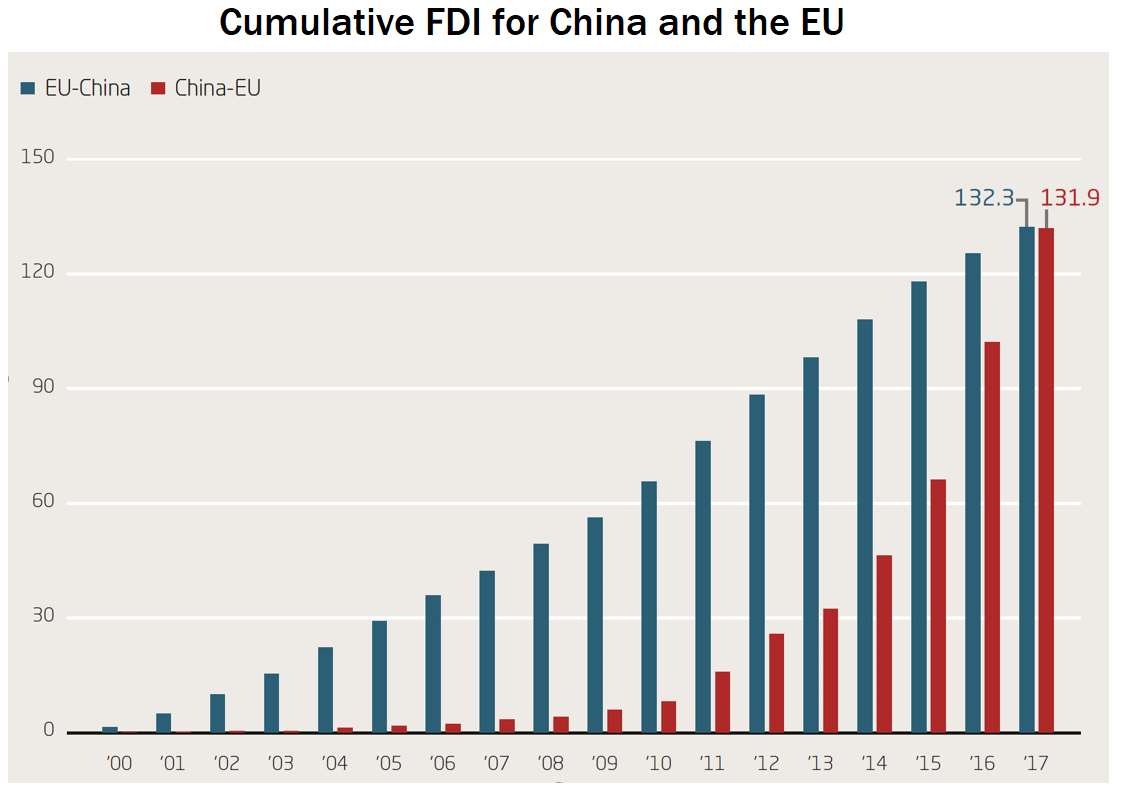

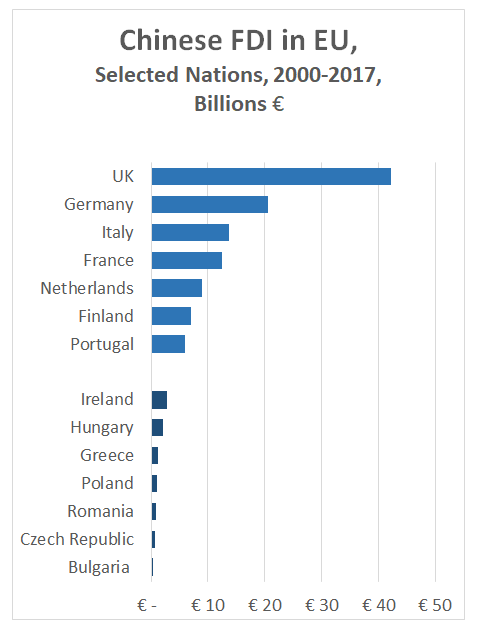

However, Europe and China are in an uncomfortable love triangle. The United States may force the EU to choose over siding with China or the US, expecting the EU to take a more hawkish attitude on designing its 5G networking platform to avoid Chinese firms. The EU confronts decisions on how close to stand with China. Some in Brussels and EU member state capitals view China as a significant challenger as well as a major growth vector. First, China has built economic connections to EU member states with unprecedented scale and speed. China’s foreign direct investment to the EU hit a record of €37 billion in 2016, up from €2.1 billion in 2010. Second, some view China’s assertive political reach as an attempt to split the EU, testing the union by giving Eastern Europe countries huge benefits in exchange for vocal advocacy of Beijing stances in international settings. China has an ambitious strategy in Eastern Europe with infrastructure projects under the China-CEEC framework – the cooperation network between China and 16 central and eastern European states – and that economic aid is vital for less wealthy countries. Portugal’s largest Atlantic port, Sines, awaits redevelopment with Chinese funding. Italy was the first of G7 countries to sign on to the Belt and Road Initiative, offering China port access. China already enjoys control of the Greek port of Piraeus. So far, 14 EU member countries have signed memoranda of understanding on BRI, despite discouragement from members like Germany. The EU is far from a uniform and single voice in its dealings with China.

The EU-US relationship faces continuous challenges spawning from trade disputes and political divergence. The Trump administration creates a dilemma for the European Union in multiple ways. The United States proposed $11 billion in tariffs towards the EU, a response to Airbus subsidies, in April, a day before the China-EU Summit. President Donald Trump’s reluctance to commit to the NATO meetings with the EU stoke worries about the transatlantic alliance. Also, Trump does not hesitate to express support for Brexit while criticizing German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s refugee policy. Trump may view Europe’s unity as a threat for the United States.

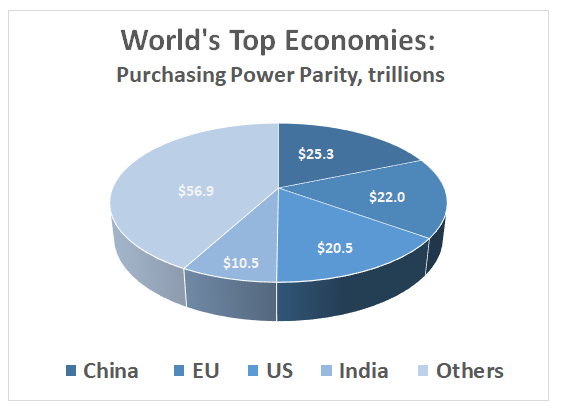

The United States, the European Union and China as the world’s three largest economies rethink approaches, and in the run-up to the summit, China’s EU envoy to Europe, Zhang Ming, called for the EU to plot its own path.

Still, increasing Chinese investment, divergences among EU member states and the changing international order have hardened Europe’s position towards China. At the midst of Europe’s fuzziness, yet a new rules-based paradigm of relationship is about to emerge, requiring greater efforts from both the EU and China. For example, a more effective investment agreement is required. Ongoing EU-China negotiations for the investment agreement must reach consensus in key areas – providing a level playing field for investors as well as creating transparent and licensing process for foreign investment.

An agreement must work for both sides, particularly as a response to emerging Chinese economic clout in the EU, easing EU suspicions. China has become a capital exporter since 2015. Since that year, more than 50 percent of China’s FDI flows to the EU consisted of mergers and acquisitions including takeover of Sweden’s Volvo, owned by Ford, from Geely; a majority stake in Germany’s robotics firm KUKA by China’s Midea; and Italy’s tiremaker Pirelli by ChemChina.

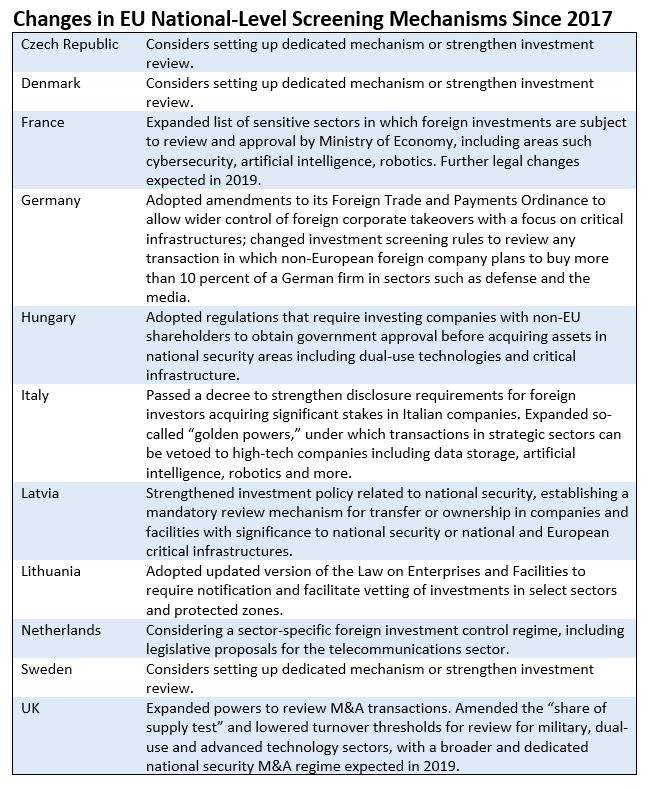

Such an investment agreement must also play a role in avoiding negative consequences that followed the EU investment-screening framework approved by the European Council in March, which concluded the legislative process. For strategic reasons, the EU proposed a mechanism seeking to ensure that FDI inflows from third countries do not compromise security and public order in member states. In that regard, member states and the European Commission consider whether a foreign investor is controlled directly or indirectly by the government of a third country.

Realistically, a common framework on screening is hard to achieve. Current screening, at most, asks member states for voluntary reporting to Brussels about proposed investments, but lacks enforcement. Not all of the EU member states have national screening systems, not to mention the varying stances on welcoming foreign investment. Also, administrative resources for screenings are costly. Increased compliance costs could lead to uncertainty and delays for acquiring firms.

Given the fact that such a mechanism could pose negative consequences for both authorities and private firms, an EU-China investment agreement is perhaps the better alternative. Such an agreement enables the EU to pursue a more open, transparent and secure environment for capital inflow, reaching more Chinese markets for capital outflow, and China can enter the Europe with fewer barriers and enjoy vibrant foreign capital to stimulate the domestic economy.

The EU and China speed negotiations on the investment agreement, hailing the breakthrough during the EU-China summit. The aim of such a rules-based agreement is to create a more conducive environment for capital flows. Europe and China, with strong codependency, will not end their marriage on trade and sectoral cooperation. They are reviewing and adding more rules for a new paradigm to make the relationship stable and sustainable. Accordingly, with the rules-based partnership principles, China’s Belt and Road Initiative may complement Europe’s Connecting Europe to Asia Strategy for further intense exchange in trade, goods, people and culture, with the goal of reciprocity and mutual benefit.

Xueying Zhang is a 2018-2019 Fox Fellow at Yale University. She is pursuing her PhD degree in International Relations at Fudan University, China. Her research interests include East Asia economic strategies, international institutions, and the world order. She is also devoted to youth contributions to global affairs and represented China in the G20 Youth summit 2017.