Shifting Terrain for India’s Foreign Policy

Shifting Terrain for India’s Foreign Policy

NEW DELHI: With a new year, Indian foreign policy faces new challenges, some of its own making and others from the turbulence generated by the changing global order.

Winning an even bigger mandate in 2019 than his first electoral victory in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi was ready to launch an ambitious agenda in the realm of foreign and national security. His unusual selection of an ex-diplomat S. Jaishankar in the powerful position of India’s external affairs minister rather than any party heavyweight shocked many. The appointment reflected Modi’s concern about the global turbulence through which Indian foreign policy must navigate and need for an experienced hand. A former foreign secretary with several key ambassadorial postings including China under his belt, Jaishankar not only underscores the priority Modi attaches to foreign policy, but also to professionalism rather than orthodoxy.

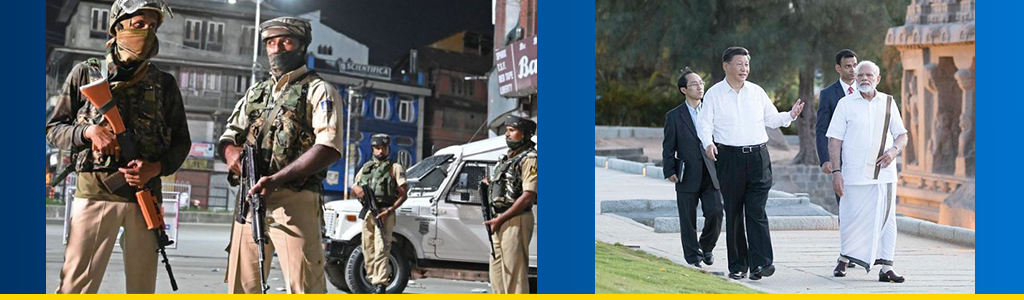

This need became pertinent in August when the Modi government took a momentous step in domestic politics with serious foreign policy implications. He suspended Article 370 via Clause 3 that had allowed Jammu and Kashmir to enjoy autonomy. The state of Jammu and Kashmir has been bifurcated into two union territories: Ladakh without a legislature; Jammu and Kashmir with a legislature. Though Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party had long signaled its intention on this front, the move was dramatic both within and outside India.

In New Delhi’s attempt to sell its Kashmir policy abroad, Jaishankar with his extensive experience and contacts around the world proved a valuable aide. In dealing with foreign repercussions, India also adopted an unusually hardball approach, challenging countries that questioned Modi’s approach.

On the wider foreign policy front, India has been busy courting major powers and reaching out to various parts of the world. Signs emerged that India’s ties with the United States were passing through a difficult phase after the Trump administration determined that New Delhi had not provided assurance of providing “equitable and reasonable access” to US markets. In June, the Trump administration then terminated India’s designation as a beneficiary developing nation under the key Generalized System of Preferences trade program. India responded by imposing retaliatory tariffs on 28 US products including almonds and apples. This came a year after announcing tariffs to counter the US increase in steel and aluminum tariffs and withdrawal of duty-free benefits to Indian exporters.

.jpg)

Nonetheless, Modi visited the United States in September, joining Trump in a joint rally organized by American-Indian groups. The goal was to reduce trade tensions with India’s leading export partner. Modi conveyed to Washington that New Delhi is ready to engage with the United States substantively in a spirit of give and take. The visit managed to reverse the relationship’s decline by reassuring Trump even as Modi reached out to the wider international community on Kashmir. Since Modi’s visit, Trump’s rhetoric towards India has softened considerably even as the two sides put final touches to a broad trade deal amid reports of Trump planning a visit to India.

Modi’s engagement with China also continued. Chinese President Xi Jinping visited India for a second informal summit with the two leaders engaging in more than five hours of one-on-one talks over two days. The Wuhan summit in 2018 did reduce tensions after the high-decibel Dokalam crisis, steering the China-India relationship from an overtly conflictual stance. The Mamallapuram summit in October 2019 was another attempt to divert the Sino-Indian conversation away from the immediate differences over Kashmir and Pakistan. Broadening the conversation to cooperation on global issues and cultural exchanges temporarily shields the relationship from the vagaries of structural challenges.

But there is also recognition in New Delhi that China is now willing to bear significant diplomatic and political costs to scuttle Indian interests. Beijing stood up for Pakistan, otherwise largely isolated, on the issue of Kashmir at the UN Security Council. Given the power differential between the two, continuous engagement with China is a veritable necessity for India even as it builds its ties with other powers and key states to develop leverage vis-à-vis China. In the context of the Indo-Pacific, India’s engagement with states like Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Indonesia has been significant with a strong focus on strategic cooperation.

Modi became the first Indian prime minister to visit the Russian Far East Region in September to give “a new direction, new energy and new speed” to relations between the two countries. His presence at the Eastern Economic Forum was useful at various levels. Russia’s Far East is a huge land mass, rich in resources, but sparsely populated and underdeveloped. With the center of gravity of global economics shifting to Asia, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin focuses on the Far East, keen on developing it with the help of Asian powers. So far, Chinese dominance in Russian Far East has been palpable, much to the discomfort of Moscow. In this context, Putin’s attempt to diversify assumes importance so as to lessen Russia’s growing dependence on China. Indian investors can also explore investment opportunities in that region and perhaps diversify the unidimensional nature of Indo-Russian ties, which continue to be driven by defense.

Apart from this, New Delhi has engaged with multiple partners and actors in the international system in an attempt to develop strategic relationships that can enhance India’s profile and further its global interests. This is as much applicable to India’s neighboring states in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region as it is to the wider Indo-Pacific and Middle Eastern states.

India’s ties with the European nations are also growing at a time when the European Union is willing to enhance its geopolitical footprint.

India has also become much more comfortable in using its economic heft to raise costs for nations that challenge Indian interests. After Turkish President Recip Tayyip Erdoğan criticized India's move to abrogate Article 370 of the constitution and supported Pakistani arguments, India not only canceled a proposed visit by Modi to Ankara, but in a first, also banned the Turkish firm Anadolu Shipyard from doing defense-related business in India.

Indian foreign policy vision is evolving – only natural for a nation that is rising in the global power hierarchy. Jaishankar articulated this vision of Indian foreign policy in a speech he gave in November in which he challenged the “dogmas of Delhi.” Jaishankar noted that India was at present standing at the “cusp” of change with “more confidence” and argued that “a nation that has the aspiration to become a leading power someday cannot continue with unsettled borders, an unintegrated region and under-exploited opportunities. Above all, it cannot be dogmatic in approaching a visibly changing world order.”

The Modi government is likely to continue on a foreign policy trajectory that will challenge long-held assumptions about the way India conducts itself on the world stage. In recent months, contestations on domestic political issues have bedeviled India’s external engagements. Yet India’s aspiration to emerge as a leading power will lead it into terrain that is at times confounding and costly. There is every indication that New Delhi is ready to bear those costs even with a weakening economy.

Harsh V Pant is director of the Studies at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi, and professor of international relations at King’s College London.