Arab Spring Success Story: Tunisians Vote

Arab Spring Success Story: Tunisians Vote

NEW HAVEN: As Tunisia prepares for an election, its fourth since a popular uprising overthrew dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, enthusiasm has subsided, and candidates have coalesced around two broad camps, offering clarity to voters. Many in the region will closely watch the electoral outcome in this country of 11.5 million that witnessed the birth of Arab Spring.

The wave of Arab Spring protests – starting in Tunisia before moving on to Egypt, Libya and Syria – jolted the region in 2011. In Egypt, a military coup stopped the democratization process. Libya and Syria now endure bloody civil wars: two governments fight in Libya, and a dictator clings to power in Syria after the Islamic State extremists occupied large sections of the nation and conducted terrorist attacks in Europe, Tunisia and beyond. Only Tunisia secured a successful, sustained peaceful transition of power from dictatorship to democracy, though Algerians have recently begun seeking real democratic transition for their country.

The September 15 election is Tunisia’s fourth since December 2010 and the second for selecting a president. Tunisia, located along the southern edge of the Mediterranean Sea, is less than 300 kilometers from Europe, and failure in the democratization process could threaten European security. The politics and procedures of democratic elections are complex, and as noted by the World Bank, the revolution for an improved economy and jobs is not yet finished. Tunisia has struggled in recent years, with GDP reaching a peak of $47 billion in 2014 and declining since. The unemployment rate exceeds 15 percent, even higher among youths, and more than 10 percent of the population lives abroad.

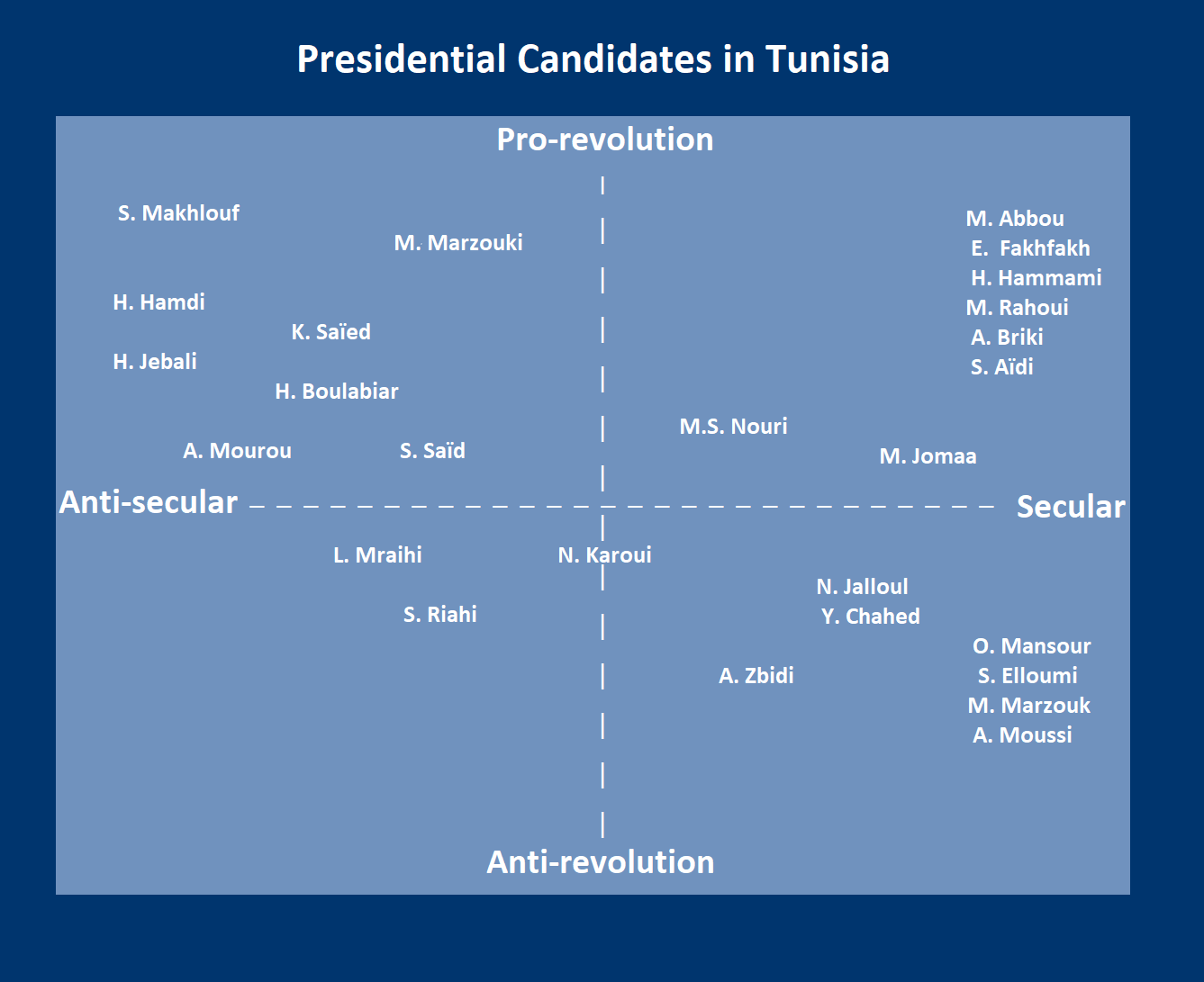

According to the new Tunisian constitution approved in 2014, the presidential elections take place in two rounds, two weeks apart. This year, 26 candidates compete in the first round to determine two finalists for the second round. The field is crowded, and the country is polarized between progressives and conservatives, much as it was for the 2014 presidential election. The first round then had 27 candidates with more than 3.3 million Tunisians voting. The top five candidates combined collected almost 3 million votes, or nearly 90 percent. The first-round finalists received more than 70 percent of the vote: Beji Caid Essebsi, who represented the liberal-progressive camp including socialists and former communists, along with well-known figures from the Ben Ali era, secured 39 percent; Moncef Marzouki representing a range of conservative and pro-revolution stances that opposed Ben Ali, received 33.4 percent. For the second round, the liberal camp delivered 1.8 million votes, or 54 percent, to Caid Essebsi who became modern Tunisia’s first democratically elected president. The revolutionary-conservative camp mustered 46 percent of the vote for Marzouki.

For this election, political opinion polls, media punditry and reactions of Tunisians on social networks reveal two trends:

● First, the public expresses considerable disgust towards the political class, which could reduce voter turnout, expected to be lower than in 2014, when 63 percent of the eligible population voted, but not as low as the 36 percent turnout for the May 2018 municipal elections. Estimates suggest candidates will be fortunate if the turnout reaches 55 percent, with participation of about 3 million voters, about 10 percent less than in 2014. About 70 percent of the country’s 11 million people are over age 18 and eligible to vote.

● Second, voters migrate between the liberal-secular and the revolutionary-conservative camps, and distribution is fluid. Estimates suggest that the liberal-progressive camp is composed of 1.5 million voters and the revolutionary-conservative camp includes 1.1 million. Voters could be described as less polarized today than in 2014, when a new political class emerged for the Tunisian public. For 23 years, all political life and power had been concentrated in one man with any opposition short-lived and as useful as a mausoleum. The election was held three years after Ben Ali stepped down and fled.

The 2014 debates focused on two personalities: Caid Essebsi and Marzouki. The first already had a tremendous political career since the Bourguiba era, summoned from retirement in 2011 for the prime minister post after the revolution and managing organization of the 2012 elections. Such prominence boosted him in the 2014 polls, and he served as president for five years, until his sudden death in July. Amid spontaneous national mourning, Tunisians advanced organization of the next elections.

Since 2014, the last five years of power in Tunisia have been characterized by a coalition between two longtime antagonists: the Islamic conservative group Nahdha and Nidaa Tounes, a political party created by Caid Essebsi in 2013 and winner of the 2014 parliamentary elections. Marzouki was not involved. In 2014, the country had 27 candidates, with Caid Essebsi the most unique representative of the liberal-progressive camp. Nahdha activists and the other part of the conservative-revolutionary camp supported Marzouki, though he didn’t receive open support from Nahdha leaders. The leaders also declined open support for Caid Essebsi. The other candidates represented various political movements with no significant impact on Tunisians.

The period since 2014 has seen many episodes of bickering among these political actors. The Nidaa Tounes party broke up into many small parties, and the conservative side had divisions, too. For example, Hamdi Jabali, head of the Nahdha government in 2012, resigned from the party and recently presented himself as an independent, therefore one of the multiple representatives of the revolutionary-conservative camp. The CPR political party, founded by Marzouki and companions like Mohamed Abbou, has almost disappeared. Several leaders went on to create their own political parties.

Candidates fall into two categories: The progressives as a group reclaim the Habiba Bourguiba legacy inspired by the reforms made by Tunisia’s first president. These reforms focused on modernization of the education system and civil code, including a ban on polygamy, making Tunisia the only country in the Arab world that has prohibited the practice. This group contains former leftist and communist sympathizers of the 1960s and 1970s who especially oppose any form of non-secularization of the state and dominance of religious power. The group of conservatives/revolutionaries is mainly composed of Tunisians who seek a more significant presence of religion in the public space, mostly composed of supporters of the Nahdha party that was severely repressed during the Ben Ali era. This group also includes part of the population that inspires significant change in the current political system. They may have leftist and progressive tendencies, but can find themselves aligned with the Islamists for radical reform of the political system.

Still, new leaders have emerged and are better known by Tunisians, and low turnout means the most passionate supporters could win the presidency. Nabil Karoui is a favorite at the polls and often compared to Silvio Berlusconi, the media tycoon and populist in Italy who served as prime minister and is now a member of the European Parliament. Abdelkerim Zbidi, a former defense minister, finds support among much of the Tunisian elite class. Youssef Chahed is the current president. Abir Moussi, a lawyer and fervent activist, has never hidden her hostilities for the conservative Nahdha party. Another personality, Kaïs Saïed, an assistant at a law university and popular in the polls, remains a favorite. Mohamed Abbou, representing some the left movement in the conservative-revolutionary camp, also counts among the favorites in this race.

Thus, in the next election, it can be safely predicted that the 39 percent obtained by Caid Essebsi in the 2014 elections may be divided among eight liberal-progressive candidates and the same could happen with the revolutionary-conservative camp. None of the five candidates mentioned is expected to capture more than 500,000 votes, or more than 20 percent.

For Tunisian voters, top issues include corruption, terrorism, unemployment and security. The second round of voting for Tunisia, October 6, should offer a clear choice, promising a sizable turnout. Otherwise, the winner’s legitimacy to govern Tunisia for the next five years could be in question.

Dhafer Malouche is currently an associate research scholar at Yale University in the Department of Statistics and Data Science and for the Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies. He’s also a professor of statistics on leave from the University of Carthage in Tunisia.

Correction: This article was updated to report that Tunisia’s GDP reached a peak of $47 billion in 2014, not $47 million. YaleGlobal regrets the error.

Update: Read about the election’s first-round results from the New York Times