Brexit and Animal Welfare in a Globalized World

Brexit and Animal Welfare in a Globalized World

WINCHESTER: With so much ink spilled in analyzing Brexit’s impact on both sides of channel, largely unnoticed is the fate of animals beyond the bipeds. The United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union may impact the welfare of billions of sentient animals on a global basis. This relates to the UK’s history in animal welfare, poor welfare standards in the US and the reality of the modern globalized world. Brexit could bring a new dawn for UK leadership in animal welfare or deliver chlorinated chicken for Sunday dinner.

In 1822, the UK passed the world’s first major animal protection law with Martin’s Act. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was established in 1824 to prosecute cases under the new act, and the UK soon outlawed dogfighting and the baiting of badgers, bears, bulls and other species. Britain later passed laws to regulate scientific experimentation on animals, prohibit cruelty to farmed animals and license other forms of animal use.

The second half of the 20th century saw rapid growth in intensive farming. Animal Machines by Ruth Harrison, 1964, chronicled how animals moved off the land to confinement in cages, treated as inanimate units of production. The UK Government commissioned a committee to investigate intensive farming, led by F.D.R. Brambell. The Brambell Report proposed that all animals should have the freedom “to stand up, lie down, groom themselves and stretch their limbs.” He recommended an expert advisory committee, which later became the Farm Animal Welfare Council, and government-funded scientific investigations on the impact of intensive farming. The Five Freedoms became the cornerstone of legislation. Countries around the world passed animal cruelty laws and founded humane societies. Governments in Europe, Australasia and the Americas established official animal welfare advisory bodies, and the discipline of animal welfare science emerged.

.png)

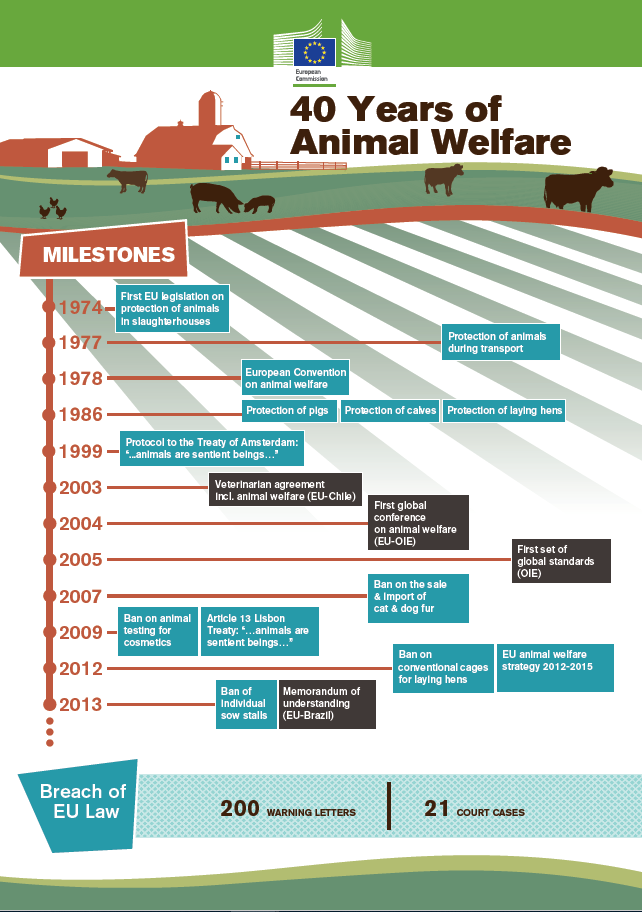

The UK joined the European Communities, precursor to the European Union, in 1973. The UK played a leading role in development of EU laws protecting animals on the farm, at transport and slaughter. In 1999 the EU formally recognized animals as sentient in its Protocol to the Amsterdam Treaty. Ultimately, the UK leveraged its economic and political influence to reform animal welfare across an EU that eventually became 28 member states with 510 million consumers. In turn, the EU influenced animal welfare on a global basis through its economic and political clout. Chile, Mexico and South Korea, for instance, have reformed animal welfare policy through trade deals and agreements with the EU.

The EU has the most progressive animal welfare laws in the world. The United States, in contrast, has some of the least developed law, as reflected by World Animal Protection Animal Protection Index scores. While the UK had long achieved the highest score of A while the US had scored a C and now score B and D, respectively. In the EU, Article 13 of the 2009 Treaty of Lisbon strengthened the Amsterdam Protocol. The EU and member states have a legal duty to pay full regard to animal welfare. The US does not formally recognize animals as sentient beings. Nor is there federal level duty to pay any regard to animals in policymaking.

In EU member states, Council Regulation 1099/2009 protects farmed animals at the time of killing. The US Humane Slaughter Act has weaker provisions and specifically exempts poultry. Given that over 95 percent of land-farmed animals slaughtered are meat chickens, the US exemption affects around 10 billion sentient birds each year. So, the majority of farmed animals slaughtered in the US have minimal or no protections at time of slaughter. Furthermore, in the EU, Council Directive 98/58/EC protects all animals used for farming purposes. Pigs, calves, meat chickens and laying hens have additional species-specific laws. There is no US federal on-farm animal welfare legislation, and state animal welfare laws in the US generally exempt conventional farming practices. In effect, most US farmed animals have minimal or no legal protection.

The three greatest moral crimes of factory farming are arguably the veal crate for calves, the barren battery cage for laying hens and the sow stall for pregnant pigs. Each entails severe confinement that causes widespread physical disease and mental suffering. The EU banned the veal calf crate in 2007, the barren battery cage in 2012 and strictly regulated the sow stall from 2013. In line with its leading role in the EU, the UK implemented the bans on veal crates earlier in 1990 and sow stalls in 1999. In the US, veal crates for calves, barren battery cages and sow stalls remain legally permitted and are widespread. Each year millions of sentient calves, hens and pigs are incarcerated in such crates, cages and stalls. A few more progressive states such as California, Michigan and Ohio have bans in place, but extreme confinement systems are routinely used across much of the US.

EU and US views clash over agriculture. The EU, recognizing animals as sentient, has the most progressive laws in the world. The US does not recognize animals as sentient and has weak or non-existent on-farm regulation. Furthermore, the EU and US have different underlying attitudes to risk and uncertainty in food production. The EU applies the precautionary principle to safeguard human health, animal welfare and the environment. US legislators permit agricultural practices unless there is substantial scientific evidence of significant harm to public health.

These fundamentally different approaches manifest as Brexit-inspired debates over food practices. US chicken carcasses are routinely washed in chlorine or a similar chemical decontaminant. The rationale is to reduce high bacterial count accrued from a stressful life in poor living conditions. The US uses five times the volume of antibiotics to keep farmed animals alive in such conditions. Despite this, US cases of Salmonella and E-Coli food poisoning in humans remain much higher than in the UK. US farmers use hormone implants in beef cattle as growth promoters and inject dairy cattle with bovine somatotrophin to increase milk yield. Pigs are injected with the growth promoter ractopamine. The EU and the UK ban these practices based on food safety and animal welfare grounds.

Brexit is a genuinely historical juncture for the UK that has enormous consequences for human society and nonhumans alike. Decisions by key policy actors during Brexit negotiations will shape UK agricultural and trade policy, impacting billions of animals. Broadly, the UK faces two choices. The UK can continue its historical trajectory as a global animal welfare leader. Free of EU shackles, it can pursue a radical reform agenda for animal welfare that is emulated around the world. Or, the UK can abandon its historical path and deregulate in animal welfare and food safety.

The first more optimistic scenario is based on the UK’s history as a leader in animal welfare. As an EU member, the UK has been held back in progressive animal welfare reform. UK governments have, for instance, argued that they could not ban live exports as a member of the EU. Outside of the EU, the UK can ban live exports and the import of fur products and foie gras. Such reforms would have major impact if replicated at an international level, for instance in the EU or Australia. Outside of the Common Agricultural Policy, the UK can reform its agricultural policy through supporting high welfare farming practices. To pursue this scenario, however, the UK must maintain its baseline high standards. The UK simply cannot import lower welfare agri-foods and remain a world leader in animal welfare.

The second more pessimistic scenario is based on the post-Brexit political and economic reality of the UK in the modern globalized world. By leaving the EU, the UK loses substantial influence on animal welfare reform in the EU27 market of 440 million strong. Globalization has greatly changed the world since 1973 when the UK joined the European Communities. Today, the US, the EU and China are the world’s three dominant trading blocs. The UK, while a major economy and political force, is not large enough to go it alone in today’s world. Any Brexiter ideology of total sovereignty is an illusion. The UK ultimately must continue substantial regulatory alignment with the EU or fall into line with the US.

The greatest direct threat Brexit poses to animal welfare is the import of lower welfare agri-foods into the UK. Consider if the UK were to import from the US just 1 percent of the total volume of chicken. This would amount to around 10 million birds annually raised and slaughtered with far lower US welfare standards. This number alone would dwarf any benefits Brexit presents such as reforming UK agricultural policy, banning live exports or prohibiting the import of fur products. If Brexit leads to the import of lower welfare agri-foods, the UK’s decision to leave the EU will necessarily be a colossal net negative for animal welfare.

Furthermore, importing lower welfare products in the UK would have a chilling effect on animal welfare. British farmers would be reluctant to improve welfare simply to be undercut by US farmers operating on a far larger scale under lower regulatory standards. Importing US agri-foods would cause a race to the bottom in economic terms. In moral terms it would mean a great betrayal of UK history, British farmers and billions of sentient farmed animals.

Steven McCulloch is senior lecturer in Human-Animal Studies at the University of Winchester, UK. He qualified as a veterinary surgeon in 2002 from Bristol University and holds a BA in philosophy from Birbeck College, London University. Steven has a PhD on the political representation of animals from the Royal Veterinary College, London. He is section editor for “Animals in Public Policy, Politics and Society” for Animals and editorial board member for the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. He is a diplomat of ECAWBM and a recognized veterinary specialist in Animal Welfare Science, Ethics and Law.