The Case for Constitutional Reform in Poland

The Case for Constitutional Reform in Poland

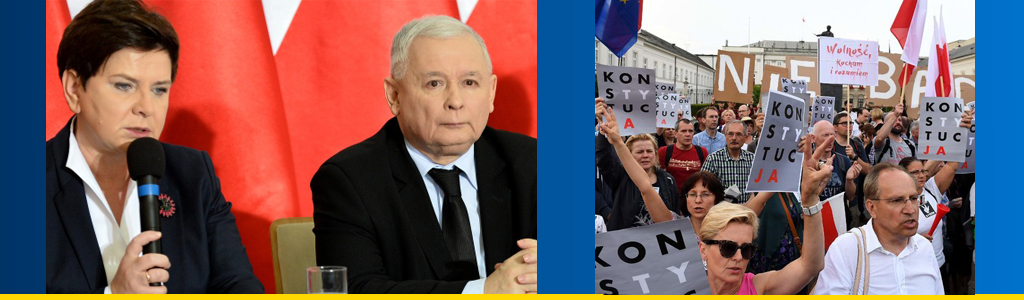

NEW HAVEN: Suppose, just for a moment, that Jaroslaw Kazcynski, the powerful boss of Poland's Law and Justice Party, fails in his authoritarian assault on democracy. Instead, his blatant power-grabs provoke a popular response reminiscent of the 1980s, a grassroots movement organizing citizen committees and public protests culminating in a sweeping repudiation of the Kazcynski regime at the polls – similar to the humiliating loss suffered by the Jaruzelski regime in June 1989.

At the moment this is a hypothetical scenario. It is up to the Polish people to determine whether the spirit of Solidarity remains a living force in the life of the nation. But serious democrats in the rest of the world should do what they can to promote this hopeful turn in Polish affairs. Most obviously, it is past time for the European Union to cut off economic assistance to the regime’s assault on foundational democratic principles.

And perhaps constitutional theorists can also make a contribution. Polish intellectuals and activists are focusing energies on organizing an effective opposition movement and have little time to consider the fundamental constitutional issues raised by the crisis.

But constitutional reforms are essential and my suggestions follow. After all, even if Poles do manage to repudiate Kazcynski’s Law and Justice Party at the 2019 parliamentary elections, there is no guarantee that another authoritarian movement won’t renew the assault on democratic government.

Of course, no constitutional reform can eliminate this danger completely. The question is whether Kaczynski’s rise was facilitated by distinctive features of Poland’s current constitution and, if committed democrats could regain power, whether they should revise the current framework to reduce future threats. The case for constitutional reform begins with a straightforward question raised by the last election: How did Law and Justice gain a majority of seats in the Sejm when it won only 38 percent of the vote? The reason is threshold requirements imposed by the election law. Two secular liberal parties narrowly failed to meet requisite thresholds – leaving 15 percent of Polish voters unrepresented in the Sejm.

This is not the first time that threshold requirements compromised the Sejm’s democratic legitimacy. In 1993, 33 percent of Poles voted for a variety of splinter-parties that failed to meet the prevailing threshold. The principal loser then was the Right, not the Left, with the resulting “democracy deficit” haunting subsequent governments. This conflict only ended when then President Lech Wałęsa dissolved the unrepresentative Sejm, calling for new elections.

The current crisis is not moving in the same direction. While President Andrzej Duda shows some independence, he would not think of challenging Kaczynski’s legitimacy on the ground that Law and Justice won only 38 percent of the popular vote.

Nevertheless, the legitimacy problem is real. If popular resistance, together with EU opposition, stops Poland’s transformation into an autocracy, the constitution should be reformed to limit the power of future governments to leverage their minority popular vote into a Sejm majority. If 15 percent or more of the votes are “wasted” on parties which fall short of the threshold, the constitution should require new elections within one year. This would create a powerful incentive for political factions to form broad-based coalitions for the next election campaign.

This constitutional reform also suggests a deeper point: Poland is not Hungary. Like it or not, the rightwing nationalism of Viktor Orbán does have support of a strong majority of the Hungarian people. In contrast, the Polish public is split three ways – one third liberal secular, one third Catholic nationalist and one third somewhere in between. It is profoundly undemocratic for antagonists of either wing to exploit parliamentary thresholds to destroy the political legitimacy of their opponents.

This principle leads to another area for constitutional reform. If and when Kaczynski is defeated, Poles should consider adopting a more “federal” constitution that would de-fuse their current bitter conflict over religious questions. Such a setup would allow liberal secularist majorities in big cities like Warsaw to insist on stronger separation of church and state within their regions while allowing more traditional majorities in rural areas to affirm a political identity rooted in Catholicism. Framing a sensible decentralization proposal would require wisdom and legal expertise since on many economic, military and social matters the central government should retain supreme powers. Nonetheless, given the intense conflict over religious issues, the question of federalism deserves attention.

For another basic question, the constitutional definition of fundamental rights, I advise a trinitarian approach – distinguishing among democratic, liberal and social rights.

Democratic rights involve the protection of interests essential for the exercise of citizenship in a free society – the right to speak, assemble, and form political parties and civil society groups aiming to promote competing visions of the public good.

These democratic rights are always under threat. Even in well-functioning systems, the government in power is tempted to pursue unfair advantages in the next election. This is why the construction of a truly independent electoral commission is a constitutional priority – and why the media must be specially insulated from political pressures.

Constitutional courts have a role to play in protecting these foundational principles. But as I have argued elsewhere, they lack the institutional resources to take on the burden of assuring an honest vote count, let alone an effective system of free and open public debate.

Law and Justice’s effort to transform the media into an engine of political propaganda serves as a cautionary tale, and the construction of a truly independent media authority deserves high priority on the reform agenda. I am more agnostic when it comes to classical liberal understandings surrounding the constitutional protection of private property. This is the issue upon which social democrats have raised a systematic protest over the past century – insisting on the authority of the state to regulate private property and to nationalize it when this serves the public interest.

In Social Justice in a Liberal State and Reconstructing American Law, I joined other contemporary theorists – notably John Rawls and Jurgen Habermas – who have tried to carve out a “third way” approach to this problem. On the one hand, we reaffirm the contributions of private property for the exercise of freedom; on the other, we emphasize that a private property system can only retain its legitimacy within an ongoing state effort to protect equal economic opportunity, environmental integrity and other fundamental values.

This “third way” position has, naturally enough, generated fierce opposition both from followers of classical liberals trying to sustain the libertarian tradition of Friedrich Hayek and from neo-Marxists aiming to reinvigorate socialism for the 21st century.

Resolution won’t be easy, and the distribution and regulation of property will be at the center of political debate in Poland and the rest of the world for the next generation. For present purposes, it’s enough to suggest that constitutional draftsmen would err in trying to terminate this debate prematurely – using their moment of political power to disqualify future democratic governments of a range of choices in organizing economic arrangements.

The challenge here is to focus on constitutional prohibition on matters, like the protection of democratic rights, which threaten clear and present dangers to political freedom.

Bruce Ackerman is Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale. His forthcoming book, The Rise of Global Constitutionalism (Harvard University Press), will analyze Polish developments in a comparative context.

A longer version of this essay was published in Polish on September 19 by Przekrój Magazine, the oldest social-cultural magazine in Poland. We thank the editors of the magazine for granting YaleGlobal permission to publish this English-language version.