Is a China-Centric World Inevitable?

Is a China-Centric World Inevitable?

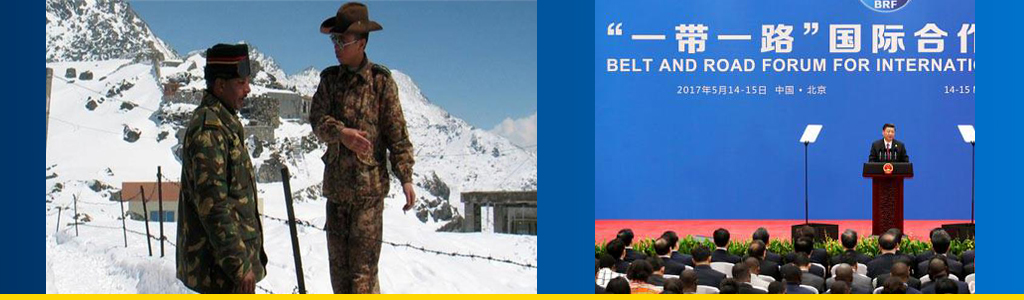

NEW DELHI: India is in a prolonged standoff with Chinese forces on the Doklam plateau. China may have been caught off guard after Indian armed forces confronted a Chinese road-building team in the Bhutanese territory.

Peaceful resolution requires awareness of the context for the unfolding events. China has engaged in incremental nibbling advances in this area with Bhutanese protests followed by solemn commitments not to disturb the status quo. The intrusions continued. This time, the Chinese signaled intention to establish a permanent presence, expecting the Bhutanese to acquiesce while underestimating India’s response.

Managing the China challenge requires understanding the history of Chinese civilization and the world view of its people formed over 5,000 years of tumultuous history. Caution is required before mechanistically applying historical patterns to the present as these are overlaid with concepts borrowed from other traditions and behavior patterns arising from deep transformations within China and the world at large.

The ideas of US naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan and British geographer Halford Mackinder are just as discernible in Chinese strategic thinking today as concepts derived from the writings of ancient strategist Sun Zi. The One Belt One Road project initiated by China is Mackinder and Mahan in equal measure: The Belt, designed to secure Eurasia, dominance over which would grant global hegemony, was suggested by Mackinder in 1904; the Road which straddles the oceans, enabling maritime ascendancy, is indispensable in pursuing hegemony, according to Mahan in the late 19th century. China’s pursuit of predominance at the top of regional and global order, with the guarantee of order, has an unmistakable American flavor. It also echoes Confucius, the Chinese sage who argued that harmony and hierarchy are intertwined: All is well as long as each person knows his place in a predesignated order.

China uses templates of the past, as instruments of legitimization, to construct a modern narrative of power.

One key element of the narrative is that China’s role as Asia’s dominant power to which other countries must defer restores a position the nation occupied throughout most of history. The period stretching from the mid-18th century to China’s liberation in 1949, when the county was reduced to semi-colonial status, subjected to invasions by imperialist powers and Japan, is characterized as an aberration. The tributary system is presented as artful statecraft evolved by China to manage interstate relationships in an asymmetrical world. Rarely acknowledged is that China was a frequent tributary to keep marauding tribes at bay. The Tang emperor paid tribute to the Tibetans as well as to the fierce Xiongnu tribes to keep peace.

History shows a few periods when its periphery was occupied by relatively weaker states. China itself was occupied and ruled by non-Han invaders, including the Mongols from the 12th to 15th centuries and the Manchus from the 15th to 20th centuries. Far from considering these empires as oppressive, modern Chinese political discourse seeks to project itself as a successor state entitled to territorial acquisitions of those empires, including vast non-Han areas such as Xinjiang and Tibet. As China scholar Mark Elliot notes, there is “a bright line drawn from empire to republic.”

Thus, an imagined history is put forward to legitimize China’s claim to Asian hegemony, and remarkably, much of this contrived history is increasingly considered as self-evident in western and even Indian discourse. Little in history supports the proposition that China was the center of the Asian universe commanding deference among less civilized states around its periphery. China’s contemporary rise is remarkable, but does not entitle the nation to claim a fictitious centrality bestowed upon it by history.

The One Belt One Road initiative also seeks to promote the notion that China through most of its history was the hub for trade and transportation routes radiating across Central Asia to Europe and across the seas to Southeast Asia, maritime Europe and even the eastern coast of Africa. China was among many countries that participated in a network of caravan and shipping routes crisscrossing the ancient landscape before the advent of European imperialism. Other great trading nations include the ancient Greeks and Persians and later the Arabs. Much of the Silk Road trade was in the hands of the Sogdians who inhabited the oasis towns leading from India in the east and Persia in the west into western China.

Thus, recasting a complex history to reflect a Chinese centrality that never existed is part of China’s current narrative of power.

China, as a great trading nation, owes its current prosperity to being part of an interconnected global market with extended value chains. This has little to do with its economic history as a mostly self-contained and insular economy. External trade contributed little to its prosperity.

Yet large sections of Asian and Western opinion already concede to China the role of a predominant power, assuming that it may be best to acquiesce to inevitability. The Chinese are delighted to be benchmarked to the United States with the corollary, as argued by Harvard University’s Graham Allison, that the latter must accommodate China to avoid inevitable conflict between established and rising power. However in other metrics of power, with the exception of GDP, China lags behind the United States, which still leads in military capabilities and scientific and technological advancements.

In reality, neither Asia nor the world is China-centric. China may continue to expand its capabilities and may even become the most powerful country in the world. But the emerging world is likely to be home to a cluster of major powers, old and new. The Chinese economy is slowing, similar to other major economies. It has an aging population, an ecologically ravaged landscape and mounting debt that is 250 percent of GDP. China also remains a brittle and opaque polity. Its historical insularity is at odds with the cosmopolitanism that an interconnected world demands of any aspiring global power.

Any emerging and potentially threatening power will confront resistance. When Bismarck created a powerful German state at the heart of Europe in the late 19th century, he recognized the anxieties among European states and anticipated attempts to constrain the expanding influence. China, like other nations before, cultivates an aura of overwhelming power and invincibility to prevent resistance. Despite this, coalitions are forming in the region with significant increases in military expenditures and security capabilities by Asia-Pacific countries.

Doklam should be seen from this perspective. The enhanced Chinese activity is directed towards weakening India’s close and privileged relationship with Bhutan, opening the door to China’s entry and settlement of the Sino-Bhutan border, advancing Chinese security interests vis-à-vis India.

India must carefully select a few key issues where it must confront China, avoiding annoyances not vital to national security. Doklam is a significant security challenge.

India must form its own narrative for shaping the emerging world order. The world’s largest democracy must resist attempts by any power to establish dominance over Asia and the world. This may require closer, more structured coalitions with other powers that share India’s preference. In fact, current and emerging distribution of power in Asia and across the globe support a multipolar architecture reflecting diffusion and diversity of power relations in an interconnected world.

India possesses the civilizational attributes for contributing to a new international order attuned to contemporary realities. Its culture is innately cosmopolitan. India embraces vast diversity and inherent plurality, yet has a sense of being part of a common humanity. India should leverage these assets in shaping a new world order that is humanity-centric. Narrow and mindless eruptions of nationalism, communalism and sectarianism detract from India’s credibility in this role. India should advance its interests, with constant awareness of responsibilities in a larger interdependent world.

Shyam Saran has served as India’s foreign secretary and as chairman of its National Security Advisory Board. He writes and speaks regularly on foreign policy and security issues. This article is adapted from the inaugural lecture delivered by the author at the Institute of Chinese Studies and the India International Centre, New Delhi.

Comments

Xi was caught red-handed trying to steal land. Now that he is cornered by the Indians, the little dragon is huffing and puffing; hissing and pi*sing. This is lose-lose situation for Xi. With the supercilious attitude and the belligerent posture of his manipulative media and military boys, if Xi doesn't attack, he loses face -- the world will laugh at him. If does attack, he loses his n*ts -- the Indians are on high grounds armed to the teeth.

And Winnie thought the world is all win-win! Ha!!

This episode is likely to end quite similar to the Chinese Mars mission: you showcase your technology, thump your chest, tell everybody how powerful you are, wave dollar bills, and even team up with the Russians; and then boom! India kicks you right in the n*tz! And you squeal back to the drawing board!!

OMG GREAT analysis. But you underestimate the Indians. They are the successors to the world. U.S. will bow to the Indians! Indians rule the world! First in the Asia, top of the world. Go India!

I would like to point out the outdated data presented in this PERSONAL opinion. China's debt is NOT 250% of its GDP, it is actually MORE than that. It is close to 300% of its GDP, which is BELOW global average. In comparison, America's debt is over 325% of its GDP, Europe's debt is also over 300% of its GDP, and Japan's debt is over 630% of its GDP. So why did the author point out China's "mounting debt" problem? My opinion is that the author has been influenced significantly by the Western "propaganda" machine.

Don't agree with me? Then, please ask yourself whether or not you knew about Japan, USA, or Europe's debt situations before reading my comment.

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that China's rail road system is SAFER that the American or European system.

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that China's air quality is bad, but it is better than India's air quality and it is IMPROVING while it is getting WORSE in India! (China has a lot more cars and does a lot more manufacturing than India). Please ask yourself whether or not you know that over 20000 people die in India due to railroad accidents.

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that Taiwan claims MORE of the South China Sea than Mainland China.

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that China has the most neighboring countries in the world and has settled MANY disputes without war.

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that China has not started any armed conflicts in the past 30 years.

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that 90% of the global population that got lifted out of poverty were Chinese (while only 20% of the global population living in poverty were Chinese. So China did the most of work lifting people out of poverty.)

Please ask yourself whether or not you know that Lancet has ranked China as one of the FIVE countries that showed the MOST improvements on its Healthcare access and quality index over the past 20 years. (While India is at where China was in 1996.)

Please ask yourself how many of the things I listed above do you know?

India can form a humanity-centric "world order"? Well, I believe it when India can do so within its OWN BORDER FIRST!

It is seriously sad to see a person in high office having to resort to lies to bolster his claims.

The article actually started very well, until it started talking about history.

For one thing, the author would have difficulty even convincing Mongolians and Manchurians that they ruled China for 300 and 500 years respectively. I don't think it would be possible to find any history textbooks in the world with such claims.

The author even makes the incredible claim that Chinese hadn't ruled China since the 12th century!! The claim that Chinese only started ruling China since after the 20th century is seriously unimaginable coming from a scholar!

As for cosmopolitanism, just about all respectable encyclopaedias of the world describe China during its Tang dynasty as one of the greatest (if not THE greatest) cosmopolitan centres of the world. The author's attempt to contradict the world's encyclopaedias is baffling!

As for trading nation, China was the biggest trading nation in the world during both the Ming and the Qing dynasties, lasting for about 500 years of human history. And of course you don't need to be the biggest trading nation to be called a trading nation. To claim it never was a trading nation (at all) is completely absurd.

It would do the author a lot of good to at least learn about history if he wants to talk about history.

=================================

Here are some reference material regarding my earlier comments :

(1) Regarding cosmopolitanism in China :

---- Lewis, Mark Edward (2012), China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03306-1

(2) Regarding China as a trading superpower during the imperial times :

---- Maddison, Angus (2007) : "Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History", Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1

(3) Regarding total period Mongolians and Manchurians ruled China :

---- (You can look at any encyclopaedia for that information. I am surprised that author didn't look.)

Just looking at this piece makes me wonder about the condition of scholarship in India. If this author, with so much "alternative-fact" was able to hold official office, how can the state of scholarship in India be taken seriously? It is so sad.

I did graduate studies in Chinese and East Asia history. It's pretty obvious that Mr. Saran is not an expert with ancient East Asian history. The Xiongnu tribes were with the earlier Han dynasty and not the Tang. Overall, it's complicated to make modern comparison to ancient foreign relationships because the world view was very different prior to the modern era. For one, there was actually no country or empire officially named "China". What we called "China" today was largely a geopolitical concept meaning the central state of its known world. The official names of the empires were the dynastic names. Ex: the Great Qing empire, the Great Ming, etc. These dynastic empires on the East Asia continent often occupied the "China" or central geopolitical position because of its size, sophistication, resources and power projection. Some of these dynasties were ruled by the ethnic Hans while in some cases the nomadic tribes like the Mongols, Manchus, Qidan, Jurchen established dynasties. Some like the Tang was actually with mixed ethic Han and nomadic Xianbei origins. But regardless, they all saw themselves as the legitimate holder of the so called "mandate of heaven" and the rightful successors to occupy the "China" or central geopolitical positions. The ability and willingness of these dynasties to project power fluctuated within each dynasty and the ambition of the imperial court. Each dynasty goes through peak and trough in relative powers. During periods of strength, the nomadic frontiers was subjugated into the empire as direct protectorates. While during times of weakness, the imperial count was not able to control the nomadic frontiers and had to appease the nomadic powers usually with political marriage. In some cases, the nomadic powers were even able to take over the empire by establishing dynasties. This was a constant pattern and really more of a intrastate relationship. Whereas relationships with states that are not directly under the imperial count were seen as vassals and tributaries (there were differences with these categories as well). This is a basic description of how the geopolitical system worked in much of East Asia prior to the 19th century which is very different with how the modern world works.

Why did the Silk Road exists? It is because the trade is valuable for people buying, the middle traders who profit from it, and for its source. So who's the end customers of the Silk Road, the Roman/western world. Who's the middle man? The nomads and middle eastern countries along its route. And who's the main seller? Chinese. Why Marco Polo want to find the source of the Silk Road? And where Columbus wanted to sail westward to reach? Even the name of this trade route is called Silk Road named after Chinese Silk. Without China, there is no Silk Road to trade or countries to profit from its trade.

Sure, Asia didn't resolve around China, only East Asia does. But mainly it is because the defensive culture of Han Chinese ethnic dynasties and geographical limits of the old world. Main Chinese expansion only happened during Mongolia and Manchu rules and rarely by any Han Chinese dynasties.

The author also confuse about that why China view its Mongolia and Manchu eras as its own dynasties. One, their dynasty consistently claimed to be part of the Chinese dynastic rule with claims of ancient heritages and justified themselves to rule over other related ethnics. They adapted their own cultures into ethnic Han culture as well. This is not too far from all the minorities ruled and claimed to be Romans. Their rules are considered to be part of Roman history and minority Caesars are also considered Roman emperors. Are all Indian kings the same ethnics?

Agree with most of your comments. The only area being the idea that only the nomadic led dynasties were “expansionary”. Most ambitious emperors regardless of ethnic background have some expansionary DNA in their world views. The Han dynasty (ethnic Han led) expanded deep into Central Asia, the Korean peninsula and south to what is now Vietnam. The Tang (mixed ethnic origin with Hans and Xianbei) at its peak was as large as the Yuan and Qing. Even the early Ming period saw military garrisons deep in the Mongolian plain. Every dynasty went through peak and trough in relative powers. During periods of strength, the nomadic frontiers were subjugated into the empire as direct protectorates. While during times of weakness, the imperial count was not able to control the nomadic frontiers and had to appease the nomadic powers usually with political marriage. In some cases, the nomadic powers were able to take over the empire by establishing dynasties. This was a constant pattern and really more of an intrastate relationship.The core factor behind all these dynastic empires since the Han dynasty was the codependency between the nomadic and sedentary backdrop.

The author does not seem to understand that "Asia" did not really exist as a concept in that part of the world today before modern times and is only a loose geographical description that is very fluid and hard to define. He seems to think that the "Chinese world view" somehow had to challenge Indian ones, which makes it necessary for him to re-write Chinese history. China was not concerned with much internal affairs of states outside of the now so-called "East Asian" area. India (no such concept as the modern India back then either) was just a collection of states far away, mysterious and fascinating to China, so there was no "Asian" order or worldview and the two countries don't have any reason to re-write history to diminish the contribution of the other in "Asia" or the world.