Digital Memorialization for a Global Age

Digital Memorialization for a Global Age

NEW HAVEN: Virtual sites of memorialization of mass atrocities, from web pages and blogs to social media, have proliferated this century. Once unimaginable technology enables individuals and communities to share photos, memories and ruminations about the past. Recent developments like holograms, artificial intelligence, virtual reality and augmented reality – AI, VR and AR – permit further changes in the very nature of memorialization, including simultaneously, and sometimes paradoxically, decentralizing and globalizing it.

Pre-digital practice mostly confined memorialization to a particular geographical space – often a monument, a museum or an archive. States produced and controlled these spaces, thus using them not only to pay respects to the heroes, victims and martyrs of its past, but also to craft narratives that supported their own claim to legitimacy.

Virtual memorialization loosens, if not shatters, such control – carrying the prospect of fundamentally changing how and where collective memory is formed and retransmitted. Digital technology allows those processes both to devolve to individuals beyond the reach of the state and communities that might transcend national boundaries. The resultant local and transnational connections may sometimes reinforce state narratives, but in other instances may serve to contest them. Previously marginalized voices may find a broader audience, while historians and their audiences have the opportunity to use and appreciate new sources and perspectives about the past. Emergent virtual communities generate their own vocabularies as well as their own touchstones for pride, grievance and understanding.

The use of social media for the memorialization of mass atrocities illustrates the global dimensions of these new trends. In countries such as Myanmar, Facebook is synonymous with the internet itself. The platform permits sharing of photos, live streaming, pre-recorded videos, stories and the ability to interact within communities of interest by commenting and “liking” posts. Residing in “the cloud,” or, more concretely, a server farm in Oregon or Sweden, Facebook commemorative or memorial pages transcend physical space, permitting individuals to form and join communities of interest from anywhere in the world.

In some cases, online memorial sites simply provide a place where people can engage with a memory in a way that is more personal, such as on pages dedicated to the legacies of particular episodes of mass violence. While not necessarily global in ambition, these sites may nonetheless produce the familiar consequence of loosening the nation-state’s grip over its historical narrative. Digital forums of memorialization of wars, genocides and mass atrocities have the power to elevate new voices, allow geographically disparate communities to share experiences and learn about their shared past, and enable others to compose their own virtual memorials outside the official domain of the state. Non-state narratives may even challenge state-driven stories, as in the cases of expatriate participants on platforms that memorialize the Igbo victims of the Biafran civil war or Armenians who demonstrate evidence of a genocidal campaign against their ancestors that today’s Turkish state maintains never happened.

These positive developments come with limitations and risks. Many states increasingly police social media sites. In some countries, individuals can be arrested for posts and sites deemed oppositional to the state. Revisionist history can also empower denialists or foment resentment at odds with projects of unity and reconciliation. Extremists might also expropriate the virtual memorialization toolkit for their own hateful purposes, gaining unprecedented global reach.

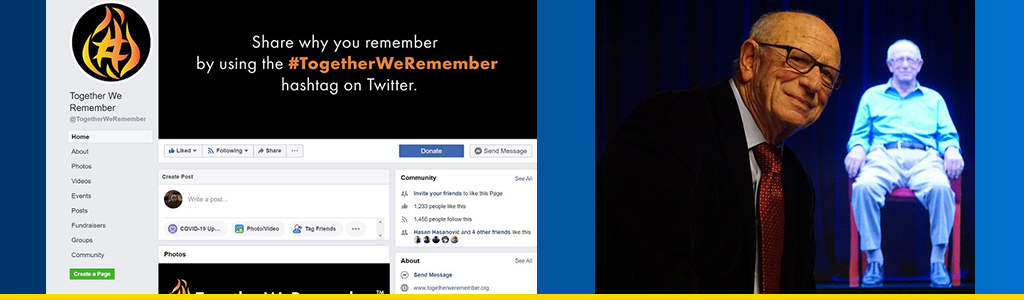

The globalizing effects of digital memorialization are not limited to those arising from digital archives and social media. Thanks to new digital technologies, physical exhibits themselves have a greater access to global space. For example, VR technology allows experiences to break free of the constraints of physical presence. While one may still need to visit a specific physical destination to experience more sophisticated versions of VR, once there the technology offers the promise of detachment, transporting the viewer to another setting, such as a concentration camp or battlefield. Similarly, hologram technology allows audiences to interact with a simulacrum, brought to their own location. The Shoah Foundation’s hologram project, for example, combines audio testimony with the illusion of a three-dimensional form of an actual Holocaust survivor, while featuring interactive capabilities driven by AI. The availability of such technology augurs to break the constraints on learning – and on sharing and processing memory – once posed by distance, geography and national borders.

In addition to connecting the past with the present, AI also connects the local and global. Programs that employ computer-learning techniques permit new ways to explore digital archives, as in the case of a project at Yale’s Fortunoff Archive of Holocaust Testimonies that seeks links across independently cultivated video testimonies, thereby permitting deeper understanding of the experiences of those who lived through the Holocaust. Another type of digital technology employed in education initiatives pertaining to mass atrocities – AR – allows users to superimpose virtual media over real-world environments and thus can render images or video onto a historical site or exhibit. These technologies, however, are not always used ethically. For example, an early instantiation of AR, Pokémon Go, had an unfortunate early intersection for genocide memorialization when its algorithm generated virtual monsters, to be found by users, on or near memorial sites like the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the memorial and museum at the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, and the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocidal Crimes in Cambodia.

Finally, virtual worlds such as Minecraft or Second Life provide alternative sites for memorial activities that transcend the duality between local and global. Participants can engage in such worlds in the intimacy of their home, while interacting with others in disparate corners of the globe. A key feature of these worlds is that while the sites within the games may replicate actual world places, they are not restrained by these boundaries. Likewise, the “players” as avatars are not easily identified as connected to any specific nation unless they choose to be. Standalone sites such as Auschwitz VR and its predecessor Witness: Auschwitz strive to narrow the distance between the local site and the global population of users – individuals, classrooms or social affinity groups.

Undoubtedly, the added dimensions of digital tools and media can change our relations to the past, one another and ourselves – and shift the meaning of commemoration, remembrance and inscription of collective memory in profound ways. Such experiences may risk losing something in the translation, as digitization involves, essentially, a fabrication. If we know something not to be real, we may be inclined to doubt it – even if the goal is to remind audiences of an urgent moment of history, never to be forgotten. What is more, as museum exhibits or online memorial sites become more like video games, risk of commodification or memory may emerge, or a race to repackage memorials as a form of macabre, if still solemn, entertainment. Will the medium – words, sounds and images ultimately reduced to binary code – change ourselves along the way?

The first half of 2020 brought a nearly global lockdown to fight the spread of Covid-19, and the ultimate paradox of the local and the global has been laid bare. Confined to our homes and apartments, we were brought perhaps more closely than ever before into direct engagement with people in similar circumstances around the world. In international Zoom conferences, virtual tourism and online memorialization events, we may be witnessing the emergence of a new norm of remote mourning and virtual commemoration. The New York Museum of Jewish Heritage’s 2020 observance of Holocaust Remembrance Day featured live-streaming speeches, prayers and readings of the names of the dead. A 24-hour vigil, “Together We Remember,” streamed over Facebook Live featuring testimonies, remembrances and performances hosted by museums and organizations from around the world. These virtual manifestations of commemoration rendered the experience accessible to a larger, more global audience than a bricks-and-mortar counterpart ceremony could possibly have attained.

Although the proliferation of digital memorialization began long before the COVID-19 pandemic, the requirements of social distancing serve to push memorialization much further into the realm of the virtual. The shift from “real” memorials to virtual ones may be viewed as an extension of globalization – yet also augers further changes. The current age of populism, nationalism and now the pandemic, each of which threatens to roll back globalization in one way or another. The turn to virtual memorialization points to a means for maintaining global connections even as globalization recedes. At the same time, it illustrates the potential for challenges to state sovereignty and conventional understandings of reality. If, in the future, the past is ultimately represented by decentralized historiography, holograms, or VR or AR tourism, how we define ourselves through our collective memories will never be the same.

Eve Zucker is lecturer in Anthropology, Columbia University. David Simon is director of the Genocide Studies Program and senior lecturer in Political Science, Yale University. They are co-editors of Mass Violence and Memory in the Digital Age: Memorialization Unmoored (Palgrave, 2020)