US Tightens Scrutiny on Foreign Investment

US Tightens Scrutiny on Foreign Investment

NEW YORK: Attempts by the US government to tighten security reviews of foreign investments runs against investor interests and could pose negative impact for the economy.

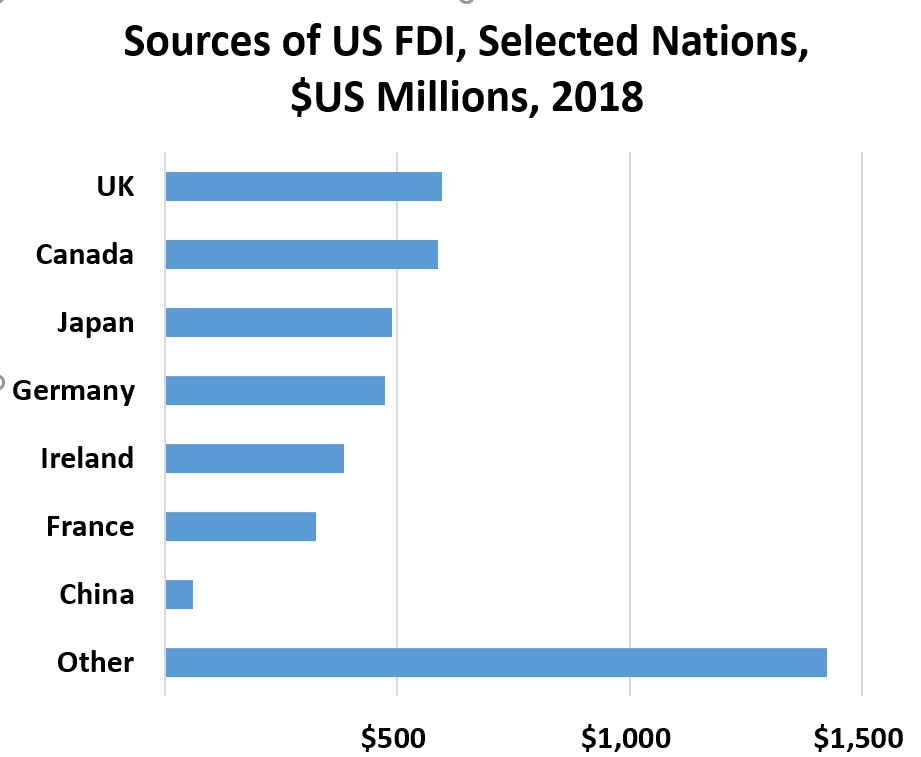

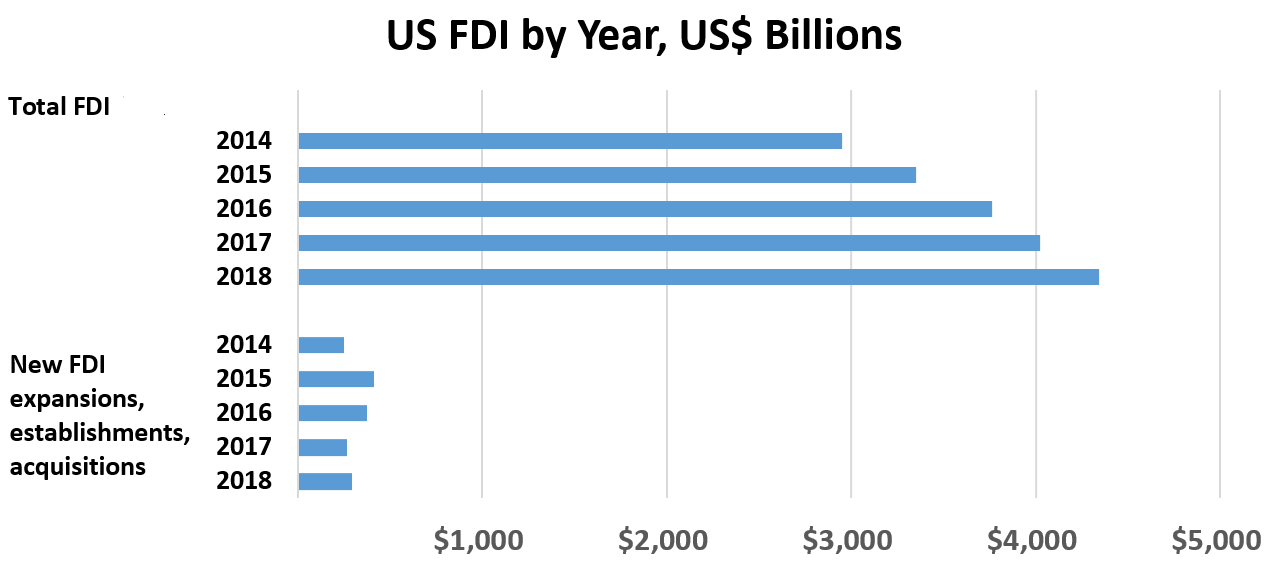

Reviews by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States have increased under the Trump administration even as the structures of companies have become more complex, and investors seek clarity. In January, the US Department of the Treasury issued final regulations implementing the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018, or FIRRMA, aiming to tighten scrutiny on foreign investments, particularly in the realm of technology.

Regulators tried to maintain collaboration between tech companies on a global scale while safeguarding the US technological edge. Yet investors express concerns about how the Treasury Department will implement FIRRMA and how tightening foreign investments may influence global technology exchange. A lack of clarity on foreign-investment regulations may be as detrimental as overly broad rules, the National Venture Capital Association explains. Uncertainty contributes to unease among international businesses and unnerves investors. And the process may ensnare companies based in countries counted among strong US allies or trade partners.

The path to regulations has been long and arduous. Congress passed FIRRMA in August 2018, strengthening the ability of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS, to review foreign investments and reject them as necessary, typically for national security concerns. Specifically, FIRRMA doubled down on the technology sector, expanding CFIUS jurisdiction to review non-controlling investments, those with a minority stake, as long as nonpublic technical information, sensitive personal data, critical technologies or infrastructures were not involved. In September 2019, the Treasury Department published proposed regulations though many key definitions remained vague, including how to define critical technologies and infrastructures.

Vague definitions triggered investors from around the world to submit comments to express concerns – some from US-allied countries like Canada and others from FIRRMA targets like China. Investors in those two camps shared some concerns and differed on others.

First, investors in both camps question if CFIUS would consider them as foreign entities, subject to intense review. For example, the proposed regulations stipulate that the term “foreign entities” may refer to entities whose principal place of business is outside the US. Yet the proposed regulations did not define how to determine the principal place of business. As noted by the National Venture Capital Association, principal place of business can be tricky to determine for global investment funds because these can be composed of multiple, separate funding sources from multiple locations, rather than a hierarchy of subsidiaries leading to a single legal entity with a headquarters. The China Chamber of International Commerce echoed similar confusion about what constitutes a foreign entity, questioning in its comment, if a company that mainly serves US customers can be considered a foreign entity if it has no US assets.

Investor concerns from allied countries and targeted countries also diverged. For investors in US-allied countries, many expressed concern about strict requirements for membership on board of directors. For an investor to obtain “excepted investor” status, requiring less scrutiny from CFIUS, the proposed regulations required each board member or observer to be a US national or a national of an “excepted foreign state.”

Such a requirement may disqualify companies based in trusted US allies, according to global law firm Shearman and Sterling. For example, Japan’s Corporate Governance Code demands that companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange appoint at least two independent directors, and many Japanese companies appoint foreign directors to their boards. This diversification of board members is also reflected among other multinational entities. Despite being a trusted partner of the US, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board includes board members who are not US or Canadian citizens. Consequently, investors from US-allied countries proposed modifications. Among the many suggestions, Canada’s institutional investor CDPQ, proposed allowing at least 33 percent of the board members of “excepted investors” to be foreign nationals.

Investors from targeted countries had more questions. For example, Chinese investors raised concerns about the acquisition of US companies that collect sensitive personal data. According to the proposed regulations, CFIUS can review non-controlling foreign investments in US companies that maintain or collect any personal identifiable data of more than 1 million individuals for a “demonstrated business purpose,” and if collecting data is integral to primary services. Such determinations can be a challenge. For example, in comments to the Treasury Department, the China Chamber of International Commerce referred to “Everyme,” a social networking application that integrates links to mainstream social networking apps like Facebook in user address books. Everyme is simply an aggregation app, mostly relying on data collected by other companies. So some argue that that the company does not have a “demonstrated business purpose” to collect data on its own nor is the collection an integral part of its services.

Many China investors consider the proposed regulations as inappropriate because of assumptions made about enterprises based on country of origin. The investors instead suggested that CFIUS give companies a separate test to determine level of risk – based on compliance history rather than place of incorporation. The Cybersecurity Association of China called the proposed regulations a violation of the World Trade Organization’s Non-Discrimination Principle and Fair Trade Principle and stated that the proposed regulations, with different treatment for different countries, defy the obligation to treat enterprises of all participating countries fairly under the WTO framework.

The US Treasury Department reviewed concerns voiced by foreign investors and issued final regulations in January, defending its position for the most part, while providing clarity on key definitions. For example, the Treasury Department included five detailed examples of companies possessing sensitive personal data that meet the criteria of CFIUS review, covering gray areas in the acquisition of data on health, geolocation and finance.

Yet the Treasury Department intentionally left some definitions broad, giving more power to CFIUS in a wider range of cases. For instance, despite investors recommending clarity in the definition of “emerging and foundational technologies,” the Treasury Department dismissed the recommendation, hinting that a list of such technologies is being prepared. The department also dismissed investor proposals on narrowing the scope of regulation on sensitive personal data, setting a time limit on retrospective reviews of completed investments and adding appeal procedures for investments rejected by CFIUS.

While most of expanded CFIUS privileges were not eliminated, the Treasury Department did make some concessions, for example, relenting on the board composition of “excepted investors.” The regulations now allow a company to still qualify as an “excepted investor” even with up to 25 percent of its board members not being citizens of the United States or “excepted foreign states.” Encryption technologies and investment funds among others also received concessions.

The changes took effect on February 13. Critics view changes as inconsequential modifications while supporters praise them as timely self-adjustments. And the Treasury Department announced that it would periodically update the final regulations. The global investment community counts on more revisions adding clarity as new questions emerge.

In all, the committee has blocked five transactions since 1975, reports the Congressional Research Service and many more investors withdrew their cases. Clear regulations provide mutual benefit for both US businesses and foreign investors. To ensure clarity, the Treasury Department must include technology experts and veteran executives with industry experience to its policy advisory committee and incorporate more detailed examples of investment categories, showing investors which CFIUS will review and which will escape scrutiny. Clear regulations provide certainty for foreign investors, whom companies need to grow and strive.

Xiaoli Jin, admitted to Harvard Law School’s Class of 2024, has written for International Social Science Review.