Vietnam May Turn Threats into Opportunity

Vietnam May Turn Threats into Opportunity

.jpg)

HANOI: So far in 2020, Vietnam has succeeded in “fighting the virus as an enemy,” as Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc quipped, reporting just over 300 confirmed Covid-19 cases and no deaths, while the rest of the world still struggles.

Yet another danger lurks in the South China Sea, a vital maritime space for not only Vietnam’s survival but that of other countries as well. To confront the danger, Vietnam openly begins cooperation with the Quad, ostensibly to manage the Covid-19 threat. Still, the United States, Japan, Australia and India formed the Quad in 2007 to confront China’s rising power.

For Vietnam, China poses an immediate threat. The gigantic Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dishi 8,escorted by armed coast guard vessels, bullied Vietnam from July to October last year near Vanguard Bank and has since returned. After cruising through Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea, the vessel moved on to bully Malaysia’s new government. Meanwhile, the Liaoning aircraft carrier strike group operated near Macclesfield Bank until 25 April when the USS America strike group left, suspending the standoff. The South China Sea may be China’s “preferred warm-up” theater for combat experience, as one Rand Corporation analyst suggested.

.png)

In response to the rising threat, Vietnam has slowly upped the ante, for the first time raising the possibility of defense cooperation with “major powers” like the United States and even of taking the South China Sea dispute to international court. On November 25, 2019, Vietnam released a new Defense White Paper, reiterating the “Three No’s” defense policy – no alliances, no foreign bases and no aligning with a second country against a third. But that policy keeps the door open to strengthening security cooperation with other countries, particularly the United States. In other words, Vietnam has a hedging strategy for deterrence of the China threat.

While other claimants in the South China Sea are reluctant to express support for freedom-of-navigation operations, the Defense White Paper reads: “Vietnam welcomes vessels of navies, coast guards, border guards, and international organizations to make courtesy or ordinary port visits or stop over in its ports to repair, replenish logistics and technical supplies.”

The paper reveals Hanoi’s increasing divergence from Beijing over how to manage the South China Sea and conveys Hanoi’s perception of critical threats, declaring its commitment to cooperation with all nations, regardless of political differences or economic disparity. The paper also signals Hanoi’s “red line” for national sovereignty and readiness to expand defense relations with major powers and other countries in the region. The paper indicates rejection of certain propositions suggesting limits for claimants in the South China Sea to participate in joint maritime activities with external powers. Instead, the paper raises the tantalizing prospect that Vietnam may consider making a strategic shift in its traditional “Three No’s” defense policy any time it faces China’s unacceptable threats, “depending on circumstances and specific conditions.”

According to Vietnamese diplomatic sources, “discussions in Hanoi about an international lawsuit are now more intense than previously.” At an annual conference on the South China Sea hosted by the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam in November, Deputy Foreign Minister Le Hoai Trung raised the issue: “The UN Charter and UNCLOS 1982 have sufficient mechanisms for us to take legal measures.”

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, known as the “Quad,” was initiated in 2007 by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, supported by US Vice President Dick Cheney, Australia’s Prime Minister John Howard and India’s Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The Australian government, under Kevin Rudd, withdrew in 2009. In hindsight, the idea was good, but the time was not quite ripe.

By November 2017, the four powers formally revived the Quad concept as a new initiative at the ASEAN and East Asia Summits. Washington took up the idea as the key driver for its new vision of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, and Donald Trump took the initiative to promote the Quad concept for security cooperation. Since then, Quad officials have met five times.

Diplomats say that Hanoi is privately considering cooperation with the Quad. To confront China’s new ambitions, Vietnam sends feelers that it could seek cooperation with the strategic group of the US, Japan, India and Australia, along with regional partners New Zealand and South Korea – a “Quad plus three.”

On March 27, the Quad members met online for the first time with New Zealand, South Korea and Vietnam, at vice-ministerial level, to discuss not only coronavirus remedies but also how to revive the economy with plans for more weekly meetings. While South Korea and Vietnam have done a good job preventing infections, the other Quad members remain busy fighting the coronavirus.

The “Quad plus three” countries have held subsequent meetings to discuss not only how to fight the pandemic, but also share technologies and get the economy back on track. There is an attempt to limit the strategic vision of the “Quad plus three” countries, and Vietnam is a key strategic partner for all four Quad members. Like India, New Zealand tries to stay neutral between the US and China and would be uncomfortable with the perception that the concept is identified as a containment strategy against China.

Yet in recent years, the strategic vision of countries in the region changed. That more countries have endorsed the Indo-Pacific vision is an indicator. ASEAN has adopted the vision of the Indo-Pacific since 2019, and steady process of the Quad’s institutionalization suggests expansion is realistic. China might find it hard to struggle to oppose regional cooperation in dealing with the coronavirus.

Derek Grossman, Rand Corporation analyst, describes Vietnam as an “intriguing case,” expected to offer excellent input to a “China-focused Quad plus.” He argues that “broadening Quad participation to include a Southeast Asian nation would weaken China’s narrative that the Quad is simply a group of extraregional powers attempting to contain China’s power.”

While Vietnamese leaders remain reluctant to go along with the Quad-plus concept, Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea may force their hand. As envisaged in the contingency clause of the Defense White Paper, Hanoi is expected to join the Quad in measured steps to avoid unnecessarily antagonizing its more powerful neighbor. Former Ambassador Pham Quang Vinh confirmed in a May 23 interview that the United States had invited Vietnam to join Quad plus, with South Korea and New Zealand, to facilitate the shifting of global supply chains and emergence of a new "economic prosperity network."

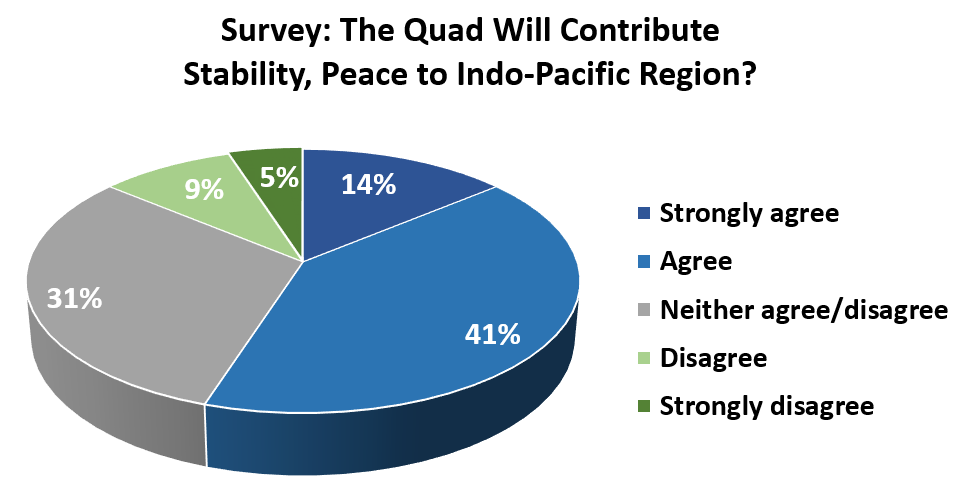

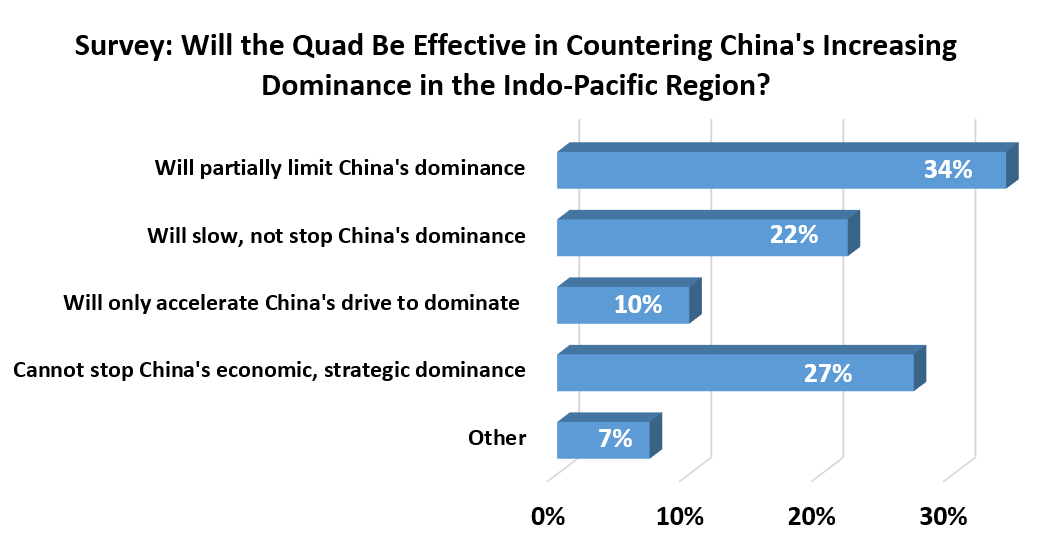

In a study conducted by Huong Le Thu, senior analyst at ASPI/ANU, most ASEAN respondents view the Quad concept as complementing ASEAN-centered security architecture. With some expressing concern about negative influence on ASEAN centrality, 57 percent of ASEAN respondents support the Quad for playing a useful role in regional security. The survey findings indicate the biggest supporters of the Quad concept are Vietnamese and Filipino respondents, who value maintaining security and stability in the region.

Meanwhile, 54 percent of ASEAN respondents suggest that the Quad’s continuity would depend on how aggressive China is, with 69 percent expressing hope that the Quad can contribute to enforcing the rules-based order. The findings contradict popular assumptions that the Quad concept is controversial and provocative. Hence, Quad expansion is slowly underway.

Alternatively, Hanoi could look to other ASEAN members – Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines – for support and cooperation in the South China Sea. China has likewise bullied and coerced these countries, rejecting their territorial claims in the South China Sea. The four countries could conduct military exercises or patrols in the South China Sea, with the Philippines unofficially floating the idea of “unity patrols.” The urge of Southeast Asian countries to unify against Covid-19 may lead to new forms of cooperation, offering benefits against China’s steady military advance.

Nguyen Quang Dy, a retired Vietnamese diplomat and Harvard Nieman Fellow 1993, is an independent researcher and freelance journalist based in Hanoi.