Why Governments Count People

Why Governments Count People

NEW YORK: Collection of population data is essential for planning and governing. From time immemorial, societies have counted and registered people for a variety of purposes, including taxation, military service, employment, voting, consumption, representation, immigration, education, public health, research, benefits and more. The methods, what meanings and rights or obligations are ascribed and who should have access to these statistics, continue to be relevant and controversial in the modern world. Governments, companies and organizations make decisions based on data, and more recently, concerns have been raised about the consequences of population growth on socio-economic development, climate change and environmental sustainability.

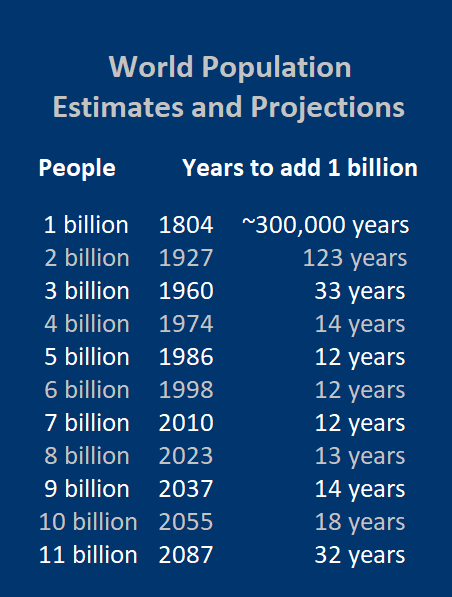

World population reached its first billion around 1804 and then grew at unprecedented rates during the 20th century, reaching 7.7 billion today. According to United Nations projections, the world’s human population is likely to reach 10 billion by 2055. For some, the consequences of a world with several billion more people expected in the coming decades are highly troubling for the planet’s sustainability. Others view the projected growth as necessary for continued economic prosperity. Population size remains controversial at the national and community levels, too, prompting worries on both demographic increase and decline.

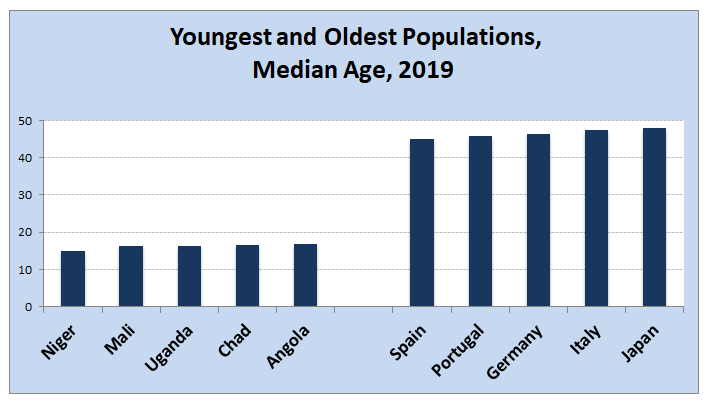

Irrespective of one’s position, demographic changes pose major challenges and opportunities for countries, regions and cities. For example, with its population expected to triple by mid-century, Niger faces enormous development difficulties in meeting citizen needs and demands. In contrast, In contrast, Japan. moves into uncharted demographic waters with its population projected to be about 15 percent smaller by mid-century.

Countries generally estimate populations by censuses, registration systems and large-scale sample surveys. Controversies over census counts emerge due to the consequences of under- or overcounts, which can influence political power and the allocation of government funds and services.

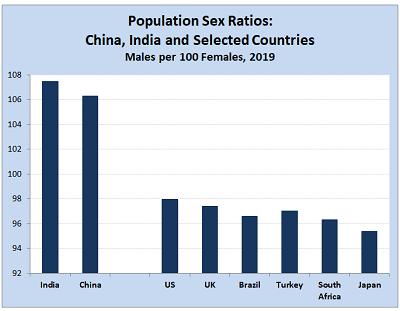

Beyond the absolute totals of people, the two most commonly enumerated characteristics of human populations are sex and age. Sex ratios offer useful insights about a population’s past and future. For example, sex ratios are useful in measuring the extent of sex-selective abortion or female feticide, the consequences of which are evident in the gender imbalances in the world’s two largest populations, China and India. In most developed countries and many developing countries, females outnumber males. By contrast, China and India both have significantly more males than females, leaving millions of men without female partners.

Traditionally, government questionnaires presented a binary choice on sex, male or female, but now include additional categories to reflect sexual orientation or gender identity that may differ from one’s biology. A number of countries – including Canada, India, Nepal and Pakistan – survey non-binary gender identities and in some instances indicate status on identification cards and passports. The United Kingdom is perhaps the first country in the world considering making the census sex question voluntary. Government research found that the binary sex question on the 2011 census was viewed as irrelevant, unacceptable and intrusive, especially to transgender people. The government considers potentially collecting details on gender identity as well as sex.

Virtually all countries measure age in years, with birth designated as age zero. Age is a critical measure, frequently utilized as the basis for activities, rights, obligations and entitlements, including schooling, driving, military service, employment, age of legal consent, voting and retirement.

Age structure also provides useful insights about a population’s needs, capacities and demographic future. For example, the median ages of Angola, Chad, Mali, Niger and Uganda, the world’s youngest countries, are below 17 years, suggesting that more government funds can be devoted toward education. The median ages of Germany, Italy, Japan, Portugal and Spain – the five oldest countries – are above 40 years and so retirement planning is emphasized.

Age is immutable, unlike most individual characteristics. Recently, however, a 69-year old man took legal action to change his age to 49 to avoid discrimination. Arguing that people can legally change their names and gender, he hoped to decide his own age, suggesting he felt much younger than his real age. The court ruled that he could not change his age.

Governments regularly collect other data across a broad spectrum of individual characteristics, including education, occupation, income, marital status, ethnicity, race, religion, language, housing, birthplace, origin of immigrant country, citizenship and disability. While some of those categories such as education or marital status are relatively straightforward, others are less clear. For example, individuals of mixed race or backgrounds might struggle to respond accurately.

Inaccuracies or outright lies defeat the purpose of the census and disrupt effective governing and meaningful planning. So every question should have a legitimate public purpose to promote well-being and reduce problems. Other concerns about the collection, use and dissemination of data that can erode accuracy include:

Privacy and confidentiality: Citizens are increasingly wary about the risks associated with disclosure of their personal information. International guidelines and policies of many countries stress the necessity of safeguarding confidentiality of government data and impose penalties for violations.

Representation: Large-scale census and registration systems often impact political representation, allocation of funds and cultural identity. In the United States, for example, some worry that inclusion of a citizenship question in the 2020 census could lead to millions of immigrants refusing to fill out their census questionnaires, leading to an undercount of residents in many states, reducing congressional apportionment and federal funding. The US Supreme Court will determine if the citizenship question is on the 2020 US census.

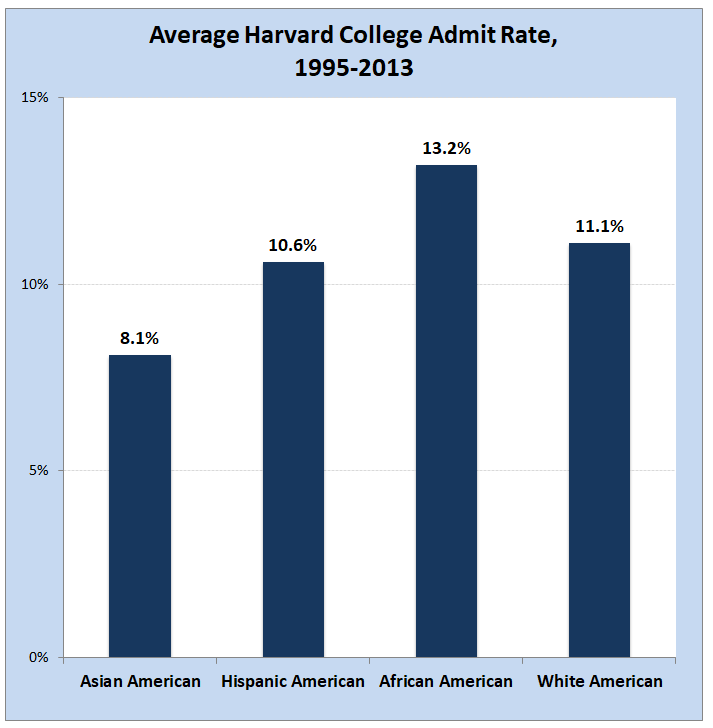

Diversity: Identifying and grouping people, while a common practice, can be a contentious issue. For example, France, Italy and the Netherlands do not count the race or ethnicity of individuals, but Brazil, China, Hungary and the United States do. Australia, Canada, Israel and the United Kingdom gather details on religious affiliation but the US census does not. Governments typically use data on ethnicity or race and religion for planning and funding services for those enumerated groups. Such categorizing can raise questions about ensuring equity, eliminating discrimination and promoting diversity. A recent US federal lawsuit against Harvard University illustrates such a challenge – students for Fair Admission accused the university of discriminating against Asian-American applicants for diversity purposes. From 1995 to 2013, Asian-American applicants had the lowest acceptance rate of any major racial group applying to Harvard.

Abuse & inequality: History provides examples of governmental authorities using census and registration data for abuse and mistreatment of certain groups among their populations. However, most governments rely on data to address differences, inequalities and discrimination in such areas as education, employment, housing, wages and voting.

Demographic data from censuses, registers and surveys contribute to democratic representation, policymaking, research, planning and administration as well as the decision-making processes of the private sector and non-governmental organizations. Most countries, including China, the United States and India require participation. Anonymous submissions are not allowed, and the counts typically link names and addresses with collected data.

In short, the counting of individuals and compiling meaningful information about them can enhance good governance and the well-being of a country’s population. However, as history has shown, government-compiled demographic data can be used for nefarious purposes, including abuse. Citizens need to understand the purposes behind any data collection, and governments must also articulate the reasons for any question. Census organizers must also apply caution, safeguards and monitoring of data-collection activities to protect privacy, ensure representation, recognize diversity, address inequalities and secure public trust.

Joseph Chamie is a former Director of the United Nations Population Division.