Everyone Can Help With Contact Tracing

Everyone Can Help With Contact Tracing

.jpg)

EAST LANSING: Covid-19 pandemic spreads around the globe, reaching into small, rural communities with few hospital beds and resources. Still, individuals can take comfort in how much control they hold over this disease by practicing good hygiene, wearing masks and adhering to social-distancing guidelines.

Add keeping a diary, calendar or daily record of activities and encounters to that list for contributing to the public good. As many communities in Europe, Asia and the Americas take steps to restart economies, public health departments rely on contact tracing to identify and isolate cases and prevent new waves of infections. “It is estimated that each infected person can, on average, infect 2 to 3 others,” notes a National Plan to Enable Comprehensive COVID-19 Case Finding and Contact Tracing in the US, from the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University. “This means that if 1 person spreads the virus to 3 others, that first positive case can turn into more than 59,000 cases in 10 rounds of infections.” Super-spreaders can infect many more people.

Some individuals, stuck at home or busy at essential jobs, immediately recognized the historical nature of this pandemic and began drafting their own personal histories. On March 15, Ruth Franklin of Brooklyn urged such diaries on Twitter: “Later, you will want a record.” Jen A. Miller, heeding that call, noted in an essay for the New York Times that writing about one’s daily life, even mundane routines, can soothe and provide order for individuals while offering insights for historians studying the pandemic’s challenges decades from now. She concludes, “Who knows, maybe one day your diary will provide a valuable window into this period.”

Some patients document their symptoms, assisting researchers. Nurses and other health providers describe the heart-breaking, exhausting and dangerous work.

Shutdowns, originally scheduled for a few weeks and then extended into months, imposed new routines and values, and others soon realized that such personal records could help with contact tracing. In mid-April, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern urged New Zealanders to keep a diary, “a quick note of where you've been and who you've been with.” Contact tracing has been a tool for New Zealand in controlling the disease. She pointed out, “Asking someone six days later to recount every movement over a period of time is an incredibly hard task."

Initially, public health officials hoped that tracking smart-phones and digital contact-tracing apps might help in spotting and containing outbreaks. Companies introduce an array of applications, to be used on a voluntary basis. In addition to privacy concerns, researchers warn about false-positive and or false-negative notifications, as well as the need an 80 percent participation rate from phone users for such the applications to be effective. Only a small percentage of people in Singapore signed on to TraceTogether application.

Manual contact tracing with interviews remains the gold standard, and the World Health Organization credited the early and extensive use of contact tracing measures in Germany and South Korea for stopping virus clusters before they went out of control. Of course, contact tracing is easier when there are only a few cases or clusters.

“Contact tracing is the process of identifying, assessing, and managing people who have been exposed to a disease to prevent onward transmission,” notes the World Health Organization. “When systematically applied, contact tracing will break the chains of transmission of an infectious disease and is thus an essential public health tool for controlling infectious disease outbreaks. Contact tracing for COVID-19 requires identifying persons who may have been exposed to COVID-19 and following them up daily for 14 days from the last point of exposure.”

To contain the virus quickly, WHO urges member states to recruit and train contact-tracing teams early when there is no or low transmissions. WHO defines a contact as anyone exposed to a Covid-19 cases, 2 days before or 14 days afterward:

• Within 1 meter, or 3 feet, for more than 15 minutes;

• Direct physical contact;

• Provide direct care for Covid-19 patients without personal protective equipment;

• Share the same household or close confined space – workplace, congregation, nursing home, or other close quarters.

WHO points out that contact tracing also requires adequate supplies of tests. Otherwise, public health authorities must ration tests and focus on high-risk groups such as nursing homes, prisons and crowded workplaces. WHO also recommends that communities encourage individuals to monitor and report symptoms as well as practice self-quarantines.

Such contact tracing, often used for preventing sexually transmitted diseases, may seem intrusive. Contact tracers should emphasize positive contributions for communities and resist presenting the questions or quarantine recommendations as punishment. “Communication about contact tracing should emphasize solidarity, reciprocity, and the common good,” the WHO document on contact tracing notes. “By participating in contact tracing, communities will contribute to controlling local spread of COVID-19, vulnerable people will be protected, and more restrictive measures, such as general stay-at-home orders, might be avoided or minimized.”

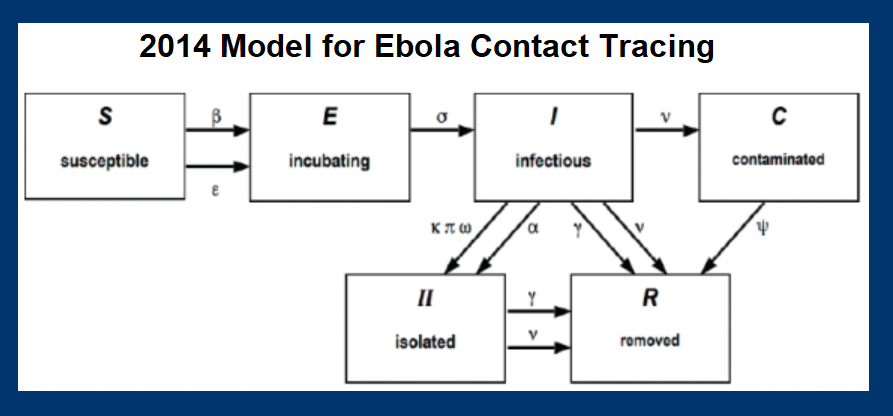

Germany relied on 10,000 contact tracers for its population of 83 million. Contact tracing in South Korea relies on patient interviews as well as monitoring of cell-phone GPS records, credit card transaction, and closed-circuit television. Taiwan linked medical records, health insurance records, and travel history to contact tracing efforts and provided a toll-free hotline. Wuhan, China, deployed 9,000 contact tracers for a population of 11 million to contain the first outbreak. Developing nations experienced with diseases like Ebola or tuberculosis are prepared and advise hiring contact tracers who know their communities and are meticulous in keeping records and maintaining confidentiality. The US Centers for Disease Control recommends strong communication skills: “Communities must scale up and train a large contact tracer workforce and work collaboratively across public and private agencies to stop the transmission of COVID-19.”

The national plan from Johns Hopkins School of Public Health suggests the United States, with a population of 328 million, needs as many as 100,000 contact tracers, paid or volunteer. Washington State considers requiring restaurants to gather names and contact details from diners. New York, New Jersey and Connecticut are joining forces on contact tracing, and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has set a goal of hiring at least 6,400 contact tracers. Partners in Health, which has worked in Haiti, Rwanda and Peru, is helping to set up a coronavirus contact tracing program with 1,000 workers in Massachusetts, reports NPR. California is organizing corps of 10,000.

Safely reopening workplaces, so that workers and clientele feel secure, requires extensive testing, contact tracing and tremendous cooperation from individuals – with diligence on distancing and pro-active self-discipline on quarantines among those who suspect exposure.

Susan Froetschel is the editor of YaleGlobal. Douglas P. Olsen teaches nursing and bioethics at Michigan State University.

.JPG)